Surface finishing processes modify the surface of a workpiece to achieve specified functional and aesthetic requirements. Mechanical, chemical and coating-based methods are the three main categories used in manufacturing, maintenance and repair. A systematic understanding of these categories supports consistent performance, reliability and compliance with technical specifications.

Fundamentals of Surface Finishing

Surface finishing targets the outer layer of a component to control properties such as roughness, hardness, residual stress, corrosion resistance, friction, reflectivity and cleanliness. It does not primarily change the bulk material composition but alters the surface to meet design and service conditions.

Key purposes include:

- Reducing surface roughness for sealing, sliding or optical performance

- Improving corrosion and wear resistance in demanding environments

- Enhancing adhesion of subsequent layers (coating, bonding, printing)

- Removing surface defects, burrs, oxides or contaminants

- Adjusting appearance: gloss, color, texture, uniformity

Mechanical processes mainly remove or plastically deform material, chemical methods primarily rely on reactions or dissolution, while coating processes add material onto the surface. These approaches can be combined in sequences suited to particular applications.

Mechanical Surface Finishing Processes

Mechanical finishing uses physical contact, abrasion or impact to shape the surface. It is widely applied because it is direct, flexible and compatible with many materials.

Grinding

Grinding uses bonded abrasive wheels to remove material and correct geometry. It is common for metals and hard materials after primary machining.

Typical characteristics:

- Material removal rate: low to medium, often 0.1–5 mm³/(mm·s) depending on wheel, speed and workpiece hardness

- Surface roughness (Ra): approximately 0.2–1.6 μm for standard finish grinding; with fine grinding and appropriate coolant, Ra can reach about 0.05–0.2 μm

- Dimensional tolerance: can routinely achieve IT6–IT7 and better with controlled conditions

Key parameters include wheel speed (commonly 20–40 m/s), workpiece speed, infeed depth (often 0.005–0.05 mm per pass), coolant flow rate and wheel specification (grain size, bond, hardness, structure). Grinding can introduce thermal damage and residual stresses if cooling and wheel conditioning are not adequate.

Polishing and Buffing

Polishing and buffing further reduce roughness and improve appearance. Polishing uses fine abrasives on flexible tools; buffing uses soft wheels and often compound pastes.

Typical outcomes:

- Surface roughness (Ra): approximately 0.01–0.1 μm for precision metal polishing

- Visual effect: from satin to mirror finish depending on sequence and abrasives

Polishing commonly follows grinding or machining. It removes a thin layer (often in the range of a few micrometers to tens of micrometers). Excessive polishing can round edges, alter critical dimensions and induce a disturbed surface layer.

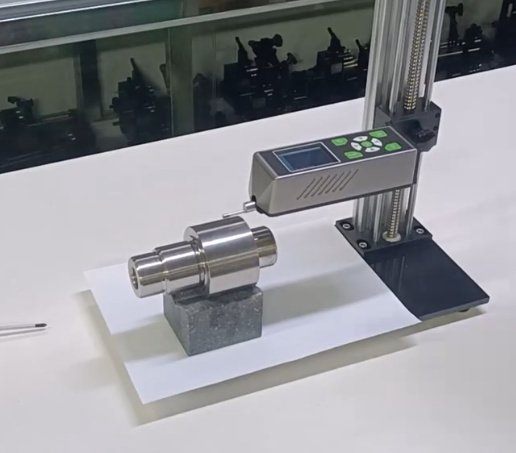

Lapping and Superfinishing

Lapping uses loose abrasive slurry between the workpiece and a flat lap plate. Superfinishing combines low-pressure abrasive stones with oscillatory motion on a rotating workpiece. These methods are used where tight dimensional and geometric tolerances and very low roughness are required.

Typical performance:

- Surface roughness (Ra): can be reduced to ≈0.005–0.02 μm

- Flatness: lapping can achieve sub-micrometer flatness over suitable areas if process is well controlled

They are common for sealing surfaces, bearing races, precision gauges and optical components. Material removal is very low and mainly improves micro-geometry rather than shape.

Deburring

Deburring removes sharp edges and burrs created by machining, drilling, blanking or cutting. It can be performed manually or by mechanical processes such as brushing, tumbling and vibratory finishing.

Typical objectives:

- Prevent assembly interference and seal damage

- Reduce risk of cracking originating at sharp edges

- Improve handling safety

The main challenge is consistent burr removal without unacceptable modification of edge geometry or dimensions, especially for precision parts and small features.

Blasting and Peening

Blasting propels abrasive media at the surface to clean, texture or prepare it. Common methods include sand blasting, shot blasting and bead blasting. Peening, particularly shot peening, uses controlled impact to induce compressive residual stresses and improve fatigue life.

Typical blasting parameters:

- Media: metallic shot, grit, glass beads, ceramic beads, corundum and others

- Pressure: generally 0.2–0.7 MPa for air blasting, depending on equipment and application

- Surface roughness: can be increased to Ra ≈1–10 μm for better coating adhesion

Shot peening parameters are usually defined by:

- Intensity: often measured with Almen strips; typical ranges depend on component and material

- Coverage: commonly specified at ≥98% for fatigue-critical parts

Blasting improves adhesion for coatings and removes scale or rust. Shot peening improves fatigue performance but roughens the surface and may require subsequent smoothing depending on the application.

Chemical Surface Finishing Processes

Chemical finishing relies on reactions between the surface and a liquid or gaseous medium. It modifies composition, morphology or cleanliness without bulk mechanical forces. It is widely used for corrosion control, preparation for coating and surface conditioning.

Chemical Cleaning and Degreasing

Chemical cleaning removes oils, oxides, scale and contaminants. Common methods include alkaline cleaning, solvent degreasing and acid pickling.

Key variables:

- Temperature: often between 30–80 °C depending on solution chemistry

- Time: typically a few minutes to tens of minutes

- Concentration: according to supplier or standard process window

Cleaning quality strongly influences adhesion and corrosion resistance of subsequent treatments or coatings. Incomplete removal of contaminants is a frequent cause of coating defects such as blisters, delamination and pinholes.

Chemical Etching

Chemical etching uses controlled dissolution to texture, pattern or remove a defined thickness from the surface. It is widely used in electronics, microfabrication, aerospace and tooling.

Typical characteristics:

- Etch rate: from a few μm/min to tens of μm/min, depending on material and chemistry

- Profile: isotropic or anisotropic, influencing edge and feature shapes

Applications include removing heat-affected layers, creating micro-roughness for bonding, and forming through-holes or channels in thin metals or semiconductor materials. Process control is critical for uniformity, dimensional accuracy and minimizing undercut.

Passivation

Passivation enhances the natural protective oxide film on corrosion-resistant materials such as stainless steels. Common solutions are nitric acid or citric acid based formulations.

Functions and parameters:

- Removes free iron and surface contaminants that could initiate corrosion

- Promotes uniform, chromium-rich passive film on stainless steels

- Typical treatment temperature: often ambient to about 60 °C

- Typical time: commonly 20–60 min depending on standard and alloy

Passivation does not significantly change dimensions or surface roughness, so it is suitable for precision components. However, proper pre-cleaning and thorough rinsing are essential to prevent spots or residues.

Conversion Coatings

Conversion coatings form an inorganic layer by chemical reaction with the substrate. Unlike simple oxides from air exposure, these are process-controlled films with well-defined properties. Examples include phosphating on steel and zinc, chromate conversion on aluminum and zinc, and non-chromate alternatives.

Typical roles:

- Improve paint or adhesive adhesion

- Provide baseline corrosion resistance, often as part of a multi-layer system

- Offer lubricity and wear control for forming or fastener applications

Key parameters:

- Coating weight: often quoted in g/m², with different ranges for light, medium or heavy coatings

- Bath temperature: often 20–95 °C depending on type

- Time: typically 1–20 min

Chromate processes for aluminum and zinc offer strong corrosion resistance and self-healing properties, but environmental and safety regulations have shifted many applications towards alternative chemistries, which are selected based on required performance and compliance requirements.

Coating-Based Surface Finishing Processes

Coating processes deposit a new layer on the surface. The layer can be metallic, ceramic, polymeric or composite. These methods are chosen when the substrate alone cannot provide required surface properties or when cost-effective performance upgrades are desired.

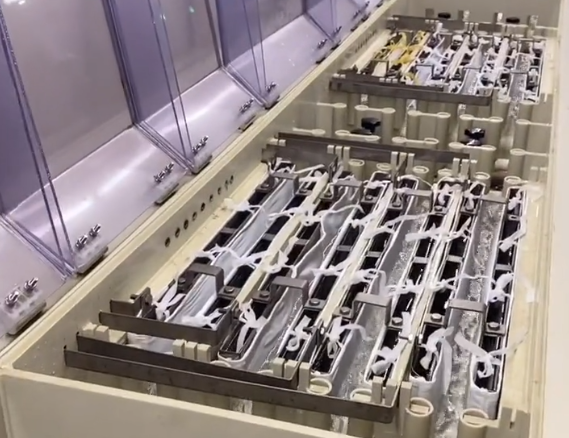

Electroplating

Electroplating deposits metal from an electrolyte onto a conductive substrate by passing electric current. Common metals include nickel, chromium, copper, zinc, tin, silver, gold and alloys.

Typical objectives:

- Corrosion protection (e.g., zinc, nickel, tin coatings)

- Decorative appearance (e.g., nickel–chrome systems)

- Electrical conductivity and solderability (e.g., copper, tin, gold)

- Wear resistance (e.g., hard chromium, nickel-based coatings)

Key process parameters:

- Current density: often in the range of 1–10 A/dm² depending on metal and bath chemistry

- Temperature: typically 20–70 °C depending on process

- Deposition thickness: from sub-micrometer flash layers up to hundreds of micrometers

Electroplating requires good surface preparation and control of solution composition, temperature, agitation and current distribution. Complex shapes can suffer non-uniform thickness, leading to thin coverage in recesses and thicker deposits on edges unless compensated by tooling and process design.

Electroless (Autocatalytic) Plating

Electroless plating deposits metal without external current by chemical reduction at the surface. Typical systems include electroless nickel (Ni-P, Ni-B) on metals and activated non-metals.

Features:

- Uniform coating thickness even on complex geometries and internal surfaces

- Good control of phosphorus or boron content for tuning hardness and corrosion resistance

- Typical thickness: commonly 5–50 μm, with higher thickness possible for special applications

Bath control is crucial because deposition rate and composition depend on temperature, pH and reactant concentrations. Deposits often require heat treatment to achieve maximum hardness or specific properties.

Anodizing

Anodizing is an electrolytic oxidation process mainly used for aluminum, but also for titanium and magnesium. It converts the surface into a thick, controlled oxide layer that is integral with the substrate.

Typical characteristics for aluminum anodizing:

- Thickness: usually 5–25 μm for decorative and general purposes; 25–100 μm for hard anodizing

- Hardness: hard anodic films can reach several hundred HV depending on alloy and process

- Porosity: oxide layer is porous and can absorb dyes and sealants

Parameters include electrolyte composition (commonly sulfuric acid for standard anodizing), current density, temperature (often 0–25 °C for different variants) and time. Sealing (hot water, steam or chemical sealing) closes pores and increases corrosion resistance.

Paints, Powder Coatings and Organic Coatings

Organic coatings include liquid paints, powder coatings and other polymer-based finishes. They form barrier layers against environment and provide color, gloss and surface texture.

Typical features:

- Thickness: liquid paints often 20–60 μm for single coats; powder coatings typically 60–150 μm

- Properties: corrosion protection, UV resistance, chemical resistance depending on resin system

- Application: spray, dip, roll, electrostatic powder spray

Curing conditions depend on formulation, often in the range of 120–200 °C for thermosetting powders and many industrial liquid coatings. Proper substrate preparation (cleaning, conversion coating, blasting) is critical for adhesion and long-term performance.

Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD)

PVD techniques, such as sputtering and evaporation, deposit thin films in vacuum. They are used for cutting tools, decorative coatings, optical layers and functional films.

Typical parameters:

- Thickness: typically 0.1–10 μm

- Substrate temperature: varies widely; common industrial ranges are about 150–500 °C depending on process and substrate limits

- Coating materials: nitrides, carbides, oxides, metals and multilayers

PVD coatings can provide high hardness, low friction, specific optical properties and improved wear or corrosion performance. Good adhesion generally requires mechanical and chemical pre-treatment such as blasting, polishing or plasma cleaning.

Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

CVD deposits solid films from gaseous precursors at elevated temperatures, often in the presence of a chemical reaction at the surface. It is used for hard coatings, diffusion barriers, dielectric layers and corrosion-resistant films.

Typical features:

- Thickness: usually in the 1–20 μm range for industrial hard coatings, with wider ranges in other applications

- Process temperature: often 500–1000 °C depending on material system

- Coating materials: carbides, nitrides, oxides, metals and composites

High process temperatures limit substrate selections. CVD coatings can have excellent adhesion and coverage, including internal surfaces, and are common for cutting tools and wear parts that tolerate higher temperatures during processing.

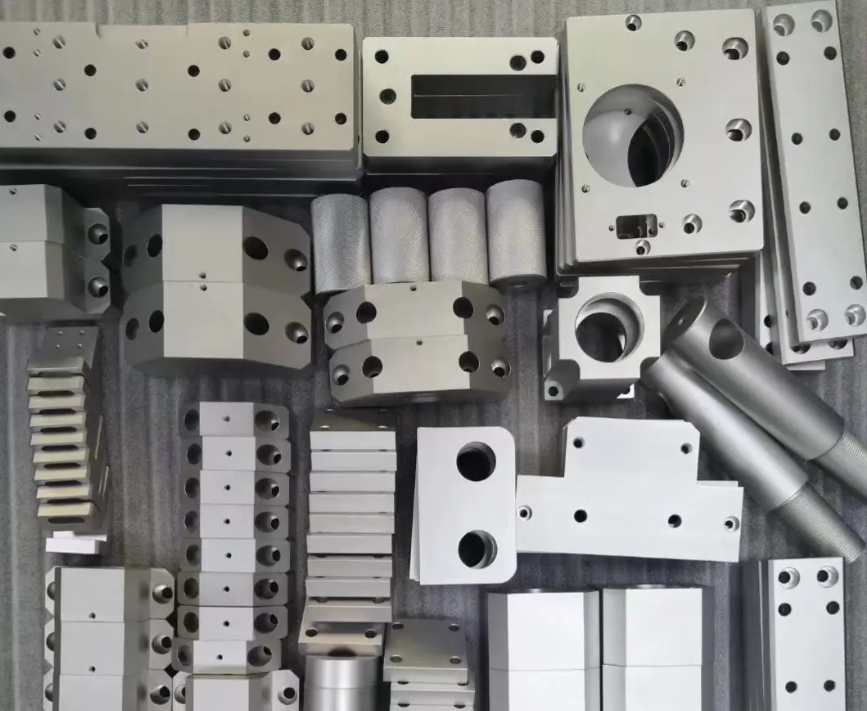

Comparative Overview of Mechanical, Chemical and Coating Methods

Each process family has distinct effects, capabilities and constraints. Selecting an appropriate method requires matching functional requirements, material properties, geometry, cost targets and production conditions.

| Category | Primary Action | Typical Thickness Change | Common Objectives | Typical Surface Roughness (Ra) Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical finishing | Abrasion, impact, plastic deformation | Material removal from ~1 μm up to several hundred μm; no added layer | Shape correction, roughness reduction, texture generation, burr removal | ≈0.005–10 μm (depending on process: superfinishing to blasting) |

| Chemical finishing | Chemical reaction or dissolution | Sub-micrometer to tens of μm removed; thin conversion films often ≤10 μm | Cleaning, passivation, conversion coating, micro-texturing | Usually minor change; can slightly etch or smooth depending on chemistry |

| Coating processes | Deposition of additional material | From <0.1 μm (thin films) to >100 μm (thick plating or paint systems) | Corrosion and wear resistance, appearance, functional properties | Determined by both substrate and coating; can smooth or replicate underlying texture |

Key Performance Parameters in Surface Finishing

Technical evaluation of surface finishing relies on quantifiable parameters. Proper specification ensures reproducibility and comparability across processes and suppliers.

Surface Roughness and Texture

Roughness is commonly expressed as Ra, Rz or related parameters. For many engineering applications:

- General machined surfaces: often Ra ≈1.6–6.3 μm

- Precision bearing or sealing surfaces: often Ra ≤0.2 μm, sometimes significantly lower

- Coating pretreatment by blasting: frequently Ra ≈2–6 μm depending on system

Profile and lay are also important. Directional roughness can influence friction, wear and sealing behavior. Surface texture (including waviness and form) may be critical for sliding interfaces and optical components.

Coating Thickness

Thickness control is essential for dimensional tolerance, protection performance and cost. Representative ranges:

- Plating: often 5–30 μm for zinc and nickel coatings on steel, with wider ranges in specialized uses

- Anodizing: typically 5–25 μm for decorative and 25–100 μm for hard anodizing

- Paint: frequently about 20–60 μm per coat for liquid; 60–150 μm for powder coatings

- PVD/CVD: commonly 0.5–10 μm for functional layers

Measurement methods include magnetic, eddy current, X-ray fluorescence, optical microscopy and destructive cross-sectioning. Non-uniform thickness can lead to early failure at thin regions or interference in tight-fit areas where coatings are thick.

Hardness and Wear Resistance

Surface hardness often correlates with wear resistance and indentation resistance. Examples:

- Base steels: often up to about 300–700 HV after heat treatment

- Hard chromium and some PVD coatings: can exceed 900–1000 HV

- Hard anodized aluminum: typically several hundred HV depending on process and alloy

However, wear performance also depends on adhesion, microstructure, lubrication conditions and contact mechanics. Hard but brittle layers may chip, while softer but tougher layers may wear gradually but remain intact.

Corrosion Resistance

Corrosion performance is influenced by coating type, thickness, porosity, substrate and environment. Standardized tests (such as neutral salt spray according to recognized methods) are frequently used as comparative indicators.

Factors that often control corrosion performance include:

- Defect density and porosity of coatings

- Quality of surface preparation and pretreatment

- Galvanic relationships between coating and substrate

- Presence and quality of sealing steps (for anodizing and conversion coatings)

Selection Criteria and Process Integration

Surface finishing is usually configured as a sequence of steps rather than a single operation. Selection is based on technical, economic and regulatory considerations.

Functional Requirements

The starting point is the required performance in service:

- Corrosion resistance in specific media (humidity, salt, chemicals, temperature)

- Wear, friction and contact conditions (rolling, sliding, impact, abrasive environment)

- Electrical, thermal and optical properties (conductivity, emissivity, reflectivity)

- Cleanliness, biocompatibility or vacuum compatibility for specialized sectors

Each requirement narrows the feasible range of processes. For instance, high-temperature service may eliminate certain organic coatings, while ultra-clean applications may favor electropolished or passivated surfaces.

Geometry and Tolerance Considerations

Geometry influences accessibility, coverage and dimensional effects:

- Internal passages, deep holes and convoluted shapes challenge mechanical access, making chemical or deposition processes more suitable

- Critical dimensions may restrict maximum coating thickness or allow only minimal material removal

- Sharp edges tend to receive thinner electroplated coatings and may require specific design or processing measures

In many cases, surfaces are machined slightly undersize or oversize to compensate for expected finishing allowances.

Material Compatibility

Substrate material strongly affects process selection:

- Aluminum: often anodized, conversion coated, painted or plated with suitable pretreatment

- Steels: ground, polished, nitrided, plated, painted or coated with PVD/CVD depending on function

- Copper alloys: commonly cleaned, passivated, plated or lacquered to control tarnishing

- Polymers: usually rely on mechanical texturing, plasma activation, painting or thin-film deposition where possible

Chemical processes must be compatible with alloy composition to avoid pitting, excessive dissolution or hydrogen uptake. Coatings must adhere reliably and avoid detrimental interactions such as embrittlement or galvanic corrosion.

Process Sequences and Pre-Treatment

Surface finishing frequently uses a multi-step chain, for example:

- Machining → grinding → polishing → cleaning → passivation

- Blasting → chemical cleaning → conversion coating → painting

- Precision machining → superfinishing → cleaning → PVD coating

Each step is designed to support the next. Poor cleaning or mechanical damage between steps can compromise the entire system. Process documentation usually specifies detailed conditions for each stage, including solutions, times, temperatures and rinsing requirements.

| Objective | Typical Substrate | Example Process Sequence |

|---|---|---|

| High-corrosion-resistance painted structure | Carbon steel | Blasting → degreasing → phosphating or other conversion coating → primer → topcoat |

| Wear-resistant cutting tool | Carbide or tool steel | Grinding → polishing or honing of cutting edges → cleaning → PVD or CVD hard coating |

| Decorative corrosion-resistant component | Zinc die casting or steel | Machining/deflashing → polishing → cleaning → copper or nickel plating → decorative chromium plating |

| Hygienic stainless component | Stainless steel | Grinding → mechanical or electropolishing → cleaning → passivation |

Typical Issues and Considerations in Surface Finishing

Several practical issues frequently arise in industrial surface finishing operations. Understanding them aids in specifying, executing and inspecting finishing processes.

Adhesion Failures

Adhesion problems can appear as flaking, blistering or delamination of coatings. Common contributing factors include:

- Inadequate cleaning or residual contaminants such as oil, oxide or polishing compounds

- Incorrect surface profile (too smooth or too rough) for the chosen coating

- Mismatched thermal expansion between coating and substrate under temperature cycling

- Insufficient pretreatment (conversion coating, activation) before plating or painting

Adhesion testing methods, such as cross-cut, pull-off and bend tests for specific systems, are used to verify performance against defined criteria.

Dimensional Changes and Tolerances

Mechanical removal processes reduce dimensions, while coatings increase them. Without proper planning, tolerances may be exceeded. Examples include:

- Grinding that removes more material than allowed, causing undersize shafts

- Plating that adds excessive thickness on critical fits, leading to assembly interference

- Hard anodizing that modifies dimensions due to both oxide growth above the surface and consumption of base metal

Designers often specify finishing allowances and may require masking or selective finishing to control dimensional changes in specific areas.

Surface Defects and Appearance

Surface finishing can reveal or create defects such as pores, pits, scratches, burn marks, waves and color variations. Sources include:

- Underlying casting or forging defects that become visible after polishing or coating

- Overheating during grinding, leading to burns or microcracks

- Non-uniform coating deposition causing color or gloss variations

Inspection procedures typically define acceptable limits for such defects based on component function and specification.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are mechanical surface finishing processes?

Mechanical surface finishing processes involve physical actions such as grinding, polishing, sanding, blasting, and brushing to alter surface texture and smoothness.

What are chemical surface finishing processes?

Chemical surface finishing processes use chemical reactions, such as etching, passivation, and chemical polishing, to modify the surface without mechanical force.

What are coating surface finishing processes?

Coating processes apply a protective or decorative layer to a surface, including anodizing, electroplating, powder coating, and painting.

How do mechanical, chemical, and coating processes differ?

Mechanical processes physically change the surface, chemical processes alter the surface through reactions, and coating processes add an additional layer for protection or aesthetics.

How do I choose the right surface finishing process?

The choice depends on material type, application requirements, environmental exposure, cost, and desired surface properties.