CNC machining is used across the entire product lifecycle, but the requirements for a prototype run and a production run are rarely the same. Understanding the differences between CNC prototyping and production machining helps engineers, buyers, and project managers select the right approach for cost, lead time, and technical performance.

Definitions and Scope

Although both rely on computer numerical control of machine tools, CNC prototyping and production machining serve distinct purposes in the lifecycle of a part.

CNC Prototyping

CNC prototyping is the use of CNC machines to produce early versions of a part or assembly. These versions are used to validate design, fit, function, performance, ergonomics or assembly before committing to large-scale production. Prototyping can occur in multiple iterations and often emphasizes agility and flexibility over unit cost.

Typical characteristics of CNC prototyping include:

- Low quantities, often from a single piece up to a few dozen or a few hundred

- Frequent design changes between iterations

- Testing of alternative materials, geometries, or tolerances

- Short setup times and simple fixturing

- Emphasis on speed, design feedback, and risk reduction

Production Machining

Production machining is the use of CNC machines to manufacture final, market-ready parts in medium to high volumes. The process is optimized for consistency, reliability, and total cost per unit over the life of a program. Engineering changes are less frequent and are carefully controlled.

Typical characteristics of production machining include:

- Medium to high quantities, from hundreds to hundreds of thousands of parts

- Stable, released designs with controlled revisions

- Optimized cycle times and tool paths

- Dedicated or semi-dedicated fixturing, tooling, and sometimes automation

- Emphasis on repeatable quality, throughput, and cost efficiency

Part Volume and Batch Size

Batch size is a fundamental differentiator between CNC prototyping and production machining. It impacts how jobs are quoted, scheduled, tooled, and inspected.

| Category | Approximate Quantity per Run | Application Focus |

|---|---|---|

| CNC Prototyping | 1–20 (early stage), up to ~100 (late stage) | Design validation, functional testing, pre-production |

| Bridge / Pilot Production | 50–5,000 | Market trials, pre-series builds, ramp-up support |

| Production Machining (Low-Mid Volume) | 500–20,000 per year | Industrial equipment, specialty vehicles, medical devices |

| Production Machining (High Volume) | 20,000+ per year | Automotive, consumer products, general hardware |

These ranges are not strict rules. A part may be machined in small batches for a long time because of low market demand, high complexity, or regulatory constraints. In such cases, production machining techniques may still be applied to reduce cost and ensure consistency.

Design Stage and Development Objectives

The stage of product development directly affects how CNC machining is applied.

Early Concept Prototypes

In early design phases, prototypes are used to answer basic questions about geometry, assembly and user interaction. Tolerances may be loose, and the emphasis is on speed and design flexibility rather than manufacturability or cost per part.

Common objectives in this phase include:

- Verifying basic form and fit with mating parts

- Exploring alternative geometries quickly

- Checking ergonomics and usability for handheld or interface parts

- Supporting internal design reviews and stakeholder demonstrations

Functional and Engineering Prototypes

Functional prototypes are closer to final parts in geometry, material, and tolerances. They may undergo mechanical, thermal, vibration, fatigue, or environmental testing. At this stage, material selection, surface finish and tolerance schemes begin to converge toward production intent.

Engineering teams use these prototypes to:

- Validate structural integrity and performance

- Confirm thermal behavior and heat dissipation

- Check sealing, pressure containment, or fluid flow

- Evaluate wear, friction, and lubrication in moving assemblies

Pre-Production and Pilot Runs

Pre-production runs use CNC machining to build parts in sample quantities for system-level validation, regulatory testing, and initial customer builds. Process capability becomes more important, and documentation such as control plans and inspection reports may be required.

Series Production

Once a design is released for production, CNC machining is configured for stable, repeatable output. Process improvements, fixture upgrades, and cycle-time reductions are justified over time by the production volume.

Process Setup, Tooling and Fixturing

Setup strategy, tooling, and fixturing differ significantly between prototyping and production machining because the economic drivers are different.

Setup Effort in Prototyping

In prototyping, setup cost must be kept low relative to the small number of parts. Machinists tend to favor flexible setups that can be adjusted quickly:

Common practices include:

- Use of modular vises, generic fixtures, and soft jaws that can be repurposed

- Limited use of dedicated automation or pallet systems

- Manual loading and unloading of parts

- Simplified tool libraries with general-purpose cutters

Programming time is often minimized using high-level CAM strategies, template setups, and conversational programming where available. Tool paths may not be fully optimized for cycle time if the total number of parts is low.

Setup Effort in Production Machining

In production machining, setup is a significant investment that is amortized across many parts. More effort is justified for:

- Designing and manufacturing dedicated fixtures

- Implementing multi-part and multi-sided workholding

- Using pallet changers, robotic loading, or bar feeders

- Optimizing tool paths for chip load, tool life, and cycle time

Machine probing, standardized work offsets, and documented setup procedures are commonly used to reduce changeover time between production batches and to maintain consistent part quality.

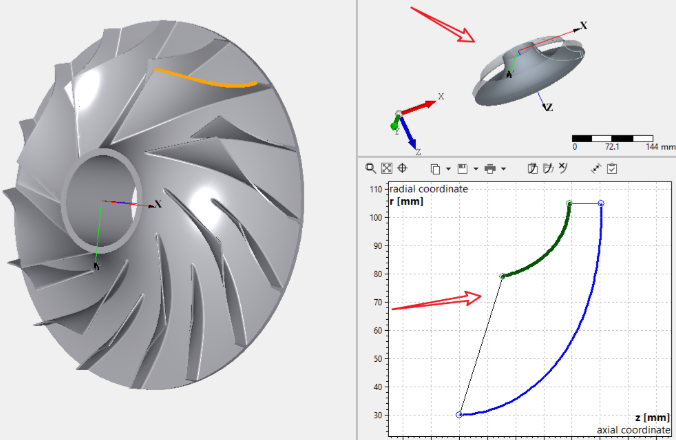

Programming, Tool Paths and Cycle Time

The way parts are programmed reflects whether the priority is speed to first article or efficiency in recurring runs.

Programming for CNC Prototyping

For prototypes:

- Programmers select machining strategies that are robust and quick to implement

- General-purpose cutting parameters are used, often with conservative feeds and speeds

- Subprograms and advanced macros are used sparingly unless they save significant time

- Optimization for cycle time is limited since total machining hours are relatively small

Because designs can change from one iteration to the next, programmers may rely on CAM toolpath templates that can be quickly updated from a revised 3D model.

Programming for Production Machining

In production:

- Cycle time reduction and tool life are key objectives

- High-efficiency roughing and rest machining strategies are common

- Feeds and speeds are tuned through test cuts and process data

- Subroutines, work coordinate systems and macros are used to manage complex operations

Manufacturers may maintain a standardized library of proven tool paths and post-processor configurations for specific machines to ensure consistency across batches and facilities.

Materials and Material Strategy

Both CNC prototyping and production machining support a wide range of materials, but the selection strategy may differ.

Materials in Prototyping

In prototyping, material selection may be influenced by availability, machinability, and cost. Engineers sometimes choose alternate grades that approximate the mechanical properties of a production material but are easier or faster to machine.

Examples include:

- Using 6061-T6 aluminum instead of a harder aluminum alloy for initial fit checks

- Using free-machining brass or mild steel for early functional prototypes

- Using engineering plastics (e.g., POM, ABS, PEEK) to evaluate shape and assembly before switching to metal

However, when performance testing is required, engineers may select the exact production material, especially for high-stress, high-temperature, or regulated applications.

Materials in Production Machining

In production machining, material choice is driven by final product requirements such as mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, weight, regulatory compliance, and cost. Supply chain stability, batch-to-batch consistency, and certification (e.g., mill test reports) are often required.

Material-related considerations include:

- Consistent machinability and hardness across batches

- Dimensional stability during and after machining

- Compatible heat treatment and finishing processes

- Long-term availability from multiple suppliers

Materials are typically standardized and locked in via specifications and drawings, leaving less room for substitution than in prototyping.

Tolerances, GD&T and Dimensional Control

Dimensional accuracy requirements influence process capability, machine selection, and inspection workload. Tolerances may be relaxed during prototyping and tightened for production, or may remain tight from the outset when required by the application.

Tolerances in CNC Prototyping

In many prototypes, designers focus on critical features and may accept larger deviations elsewhere, as long as fit and function are validated.

Typical patterns in prototyping include:

- Use of general tolerances based on ISO 2768 or title-block notes for non-critical features

- Tight tolerances only on features under active evaluation (e.g., mating bores, sealing surfaces)

- Flexibility to adjust tolerances between design iterations based on test feedback

Inspection may be limited to key dimensions on a small sample of parts, especially when the main objective is qualitative validation.

Tolerances in Production Machining

In production, tolerance requirements are stable and documented. The machining process is selected and controlled to meet these requirements reliably over time.

Key aspects include:

- Defined tolerance schemes and GD&T callouts for functional features

- Capability studies (Cp, Cpk) on critical characteristics

- Control of tool wear, thermal growth and machine calibration

- Process adjustments based on measured data

For high-precision parts (for example, with tolerances in the range of ±0.005 mm to ±0.01 mm), machine selection, tooling, environment and inspection methods are all planned to support the required capability.

Surface Finish and Cosmetic Requirements

Surface finish is another area where prototyping and production machining differ, both in specifications and in process control.

Surface Finish in Prototyping

Prototype parts may prioritize function over appearance, depending on the application. As a result:

- Standard machined finishes may be acceptable on most surfaces

- Critical surfaces might be polished or treated locally

- Secondary finishing such as bead blasting or anodizing may be used selectively for demonstration samples

When prototypes are used for marketing presentations or user evaluations, cosmetic requirements may be stricter, but the inspection is often visual and qualitative rather than formalized.

Surface Finish in Production Machining

Production parts require consistent surface finish, defined numerically where applicable. Typical metrics include Ra (arithmetical mean roughness) and Rz (average maximum height).

In production machining:

- Specific Ra values are assigned to functional and cosmetic surfaces

- Processes are standardized (cutting parameters, tool type, finishing operations) to meet these values

- Sampling plans define how often surface finish is measured

- Subsequent operations such as coating, plating, or painting are coordinated with the machined finish

Repeatable surface quality may require stable tool wear management and periodic machine maintenance.

Lead Time, Turnaround and Scheduling

Lead time expectations for CNC prototyping and production machining are driven by different usage scenarios, even though both processes share similar equipment.

Lead Time in CNC Prototyping

Prototyping is often time-critical. Design teams may request parts within days to maintain development momentum. Consequently:

- Machines are scheduled flexibly to insert small prototype runs between larger jobs

- Setup reduction and rapid programming are prioritized

- Material may be drawn from existing stock rather than waiting for optimized bulk purchases

- Shipping methods are chosen to minimize total time to test or review

Lead times for simple prototypes can range from 1–7 days, depending on part complexity, material availability, and shop capacity.

Lead Time in Production Machining

Production lead time is determined by the sum of setup, machining, finishing, inspection, packaging and logistics for batch quantities. Schedule stability is more important than absolute speed.

Typical features of production scheduling include:

- Repetitive production orders with fixed or forecasted quantities

- Allocated machine time based on capacity planning

- Lead time that includes material procurement and subcontracted operations

- Buffer stocks or safety inventory to absorb demand variations

For mature parts, production lead times are often predictable and integrated into customers’ MRP or ERP systems.

Cost Structure and Pricing

Cost structure differs significantly between one-off prototypes and high-volume production. Understanding what drives cost helps in making informed decisions when moving from prototyping to production machining.

Cost Drivers in CNC Prototyping

In prototyping, the main cost elements are:

- Programming and engineering time

- Setup time for small batches

- Raw material cost in relatively small quantities

- Machine time based on actual cutting and handling

- Finishing and inspection proportional to project requirements

The cost per part can be high because non-recurring efforts such as part programming and manual setup are spread over only a few pieces. Nonetheless, this is often acceptable because the objective is learning and validation, not unit cost optimization. The financial risk of discovering design issues in small batches is much lower than in large production runs.

Cost Drivers in Production Machining

In production machining, unit cost is sensitive to cycle time, tool life, material utilization and overhead allocation. Typical cost contributors include:

- Tooling and fixture design and manufacturing

- Machine amortization and labor

- Raw material, often purchased in larger quantities at better pricing

- Quality control, documentation and certifications

- Packaging and logistics

Non-recurring engineering and tooling costs are amortized over many parts, reducing their impact on each unit. For high volumes, even small reductions in cycle time or scrap rate can yield significant cost savings.

Quality Control, Inspection and Documentation

Both CNC prototyping and production machining require quality control, but the scope and depth differ because the consequences of defects are different.

Quality in CNC Prototyping

Prototype parts are often evaluated by design and test engineers rather than formal quality systems. Inspection may focus on verifying key dimensions and features essential to the specific tests planned.

Typical characteristics include:

- First article inspection of critical dimensions

- Use of calipers, micrometers, pin gauges and height gauges

- Limited or no use of formal statistical process control

- Documentation tailored to internal development needs rather than external audits

CMM reports or advanced inspection may be used for complex geometries, especially when prototypes also serve as reference parts for future production.

Quality in Production Machining

Production machining requires repeatable compliance with specifications over time. Quality management systems, such as ISO 9001 or industry-specific standards, may govern how processes are controlled and documented.

Quality control features may include:

- Incoming inspection of raw materials with traceability

- In-process checks at defined intervals or after specific operations

- Use of CMMs, optical measurement, or specialized gauges for critical features

- Statistical process control and capability analysis

- Final inspection with documented measurement records

Customers may require detailed documentation such as inspection reports, material certificates, process FMEAs, or control plans as part of the production release.

Equipment, Machine Types and Process Selection

The same general types of CNC equipment can be used for both prototyping and production machining, but the way they are deployed is different.

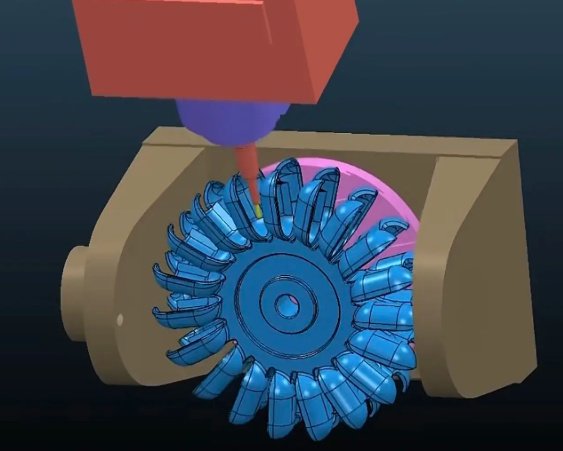

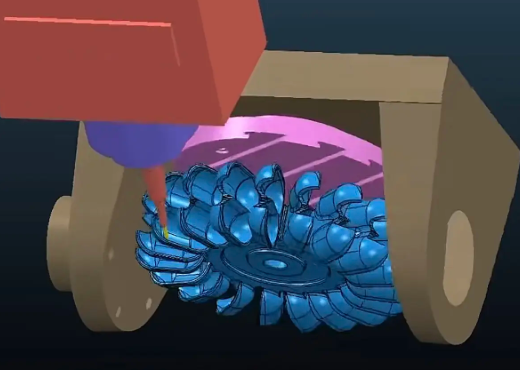

Machines Commonly Used in Prototyping

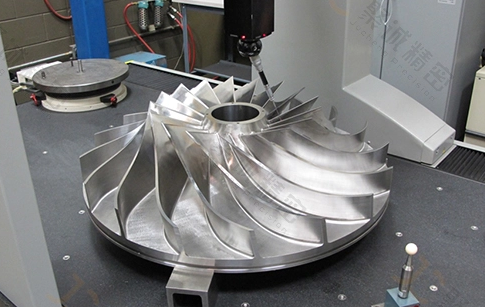

Prototyping often relies on flexible equipment capable of handling diverse part geometries and quick changeovers, such as:

- 3-axis vertical machining centers (VMCs)

- 4-axis and 5-axis machining centers for complex geometries

- CNC lathes with simple or live tooling for turned prototypes

- Mill-turn centers where both milling and turning are required on a single part

The focus is on versatility rather than maximum throughput. Machines may be programmed directly on the shop floor or via CAM systems with rapid turnaround.

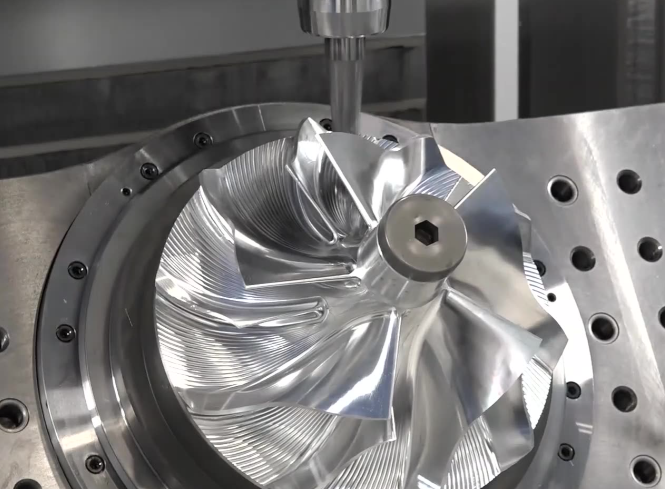

Machines Commonly Used in Production Machining

Production machining uses similar categories of machines but often in more specialized or automated configurations:

- Horizontal machining centers (HMCs) with pallet systems for high volume

- Multi-spindle and multi-turret lathes for high-throughput turning

- Dedicated mill-turn or transfer lines for complex high-volume parts

- Robotic loading systems integrated with machining centers

Machines may be dedicated to specific families of parts, and tooling libraries are standardized to minimize changeover time and variability.

Pain Points and Practical Considerations

Using CNC machining effectively from prototype to production requires attention to several practical issues that impact time, cost and product performance.

Design for Manufacturability (DFM) Across Stages

Designs that are straightforward to machine for prototypes may become expensive or slow at production volumes if not optimized. Common DFM considerations include:

- Minimizing deep pockets and thin walls that require small tools or multiple setups

- Avoiding unnecessary tight tolerances on non-critical features

- Standardizing hole sizes, threads and radii where possible

- Orienting parts to reduce the number of operations and setups

Addressing manufacturability during the prototyping phase helps maintain continuity when moving to production machining.

Transition from Prototype to Production

The transition step is where many issues appear if not managed systematically. Differences between prototype and production setups can affect tolerances, surface finish, and even material properties if heat treatment or finishing processes change.

Practical steps to manage this transition include:

- Documenting prototype process parameters as a starting reference

- Defining which prototype characteristics are mandatory in production and which can change

- Creating pre-production builds that use the intended production equipment and tooling

- Comparing prototype and production parts via dimensional and functional testing

Consistent communication between design, manufacturing engineering, and machining suppliers is essential to ensure that critical functional requirements are preserved.

Typical Use Cases and Application Examples

Different industries leverage CNC prototyping and production machining in specific ways, based on product complexity and regulatory environment.

Automotive Components

Automotive development often uses CNC prototyping for early engine, transmission, suspension, and structural parts to support testing long before production tooling is ready. Parts might be machined from billet rather than castings to accelerate development.

Once designs are frozen, production machining is used for high-volume components such as brackets, housings, shafts, and precision machined castings, often with dedicated fixtures and automated handling.

Medical Devices

In medical device development, CNC prototyping provides components for clinical samples, usability studies, and biocompatibility testing. Regulatory documentation may require traceability even at the prototype level.

Production machining then supports serial manufacturing of implants, surgical instruments and diagnostic equipment components, with tight control of material traceability, surface finish and cleaning processes.

Aerospace Parts

Aerospace prototypes include structural brackets, actuators, components for test rigs, and assemblies for flight testing. Prototypes may require the same alloys and heat treatment as production parts due to performance and safety requirements.

Production machining covers long-running programs, with parts manufactured under strict process control, controlled documentation, and often special process approvals from aircraft manufacturers.

Comparison Summary

The following table summarizes key differences between CNC prototyping and production machining across major dimensions.

| Aspect | CNC Prototyping | Production Machining |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Design and functional validation | Consistent, cost-efficient part supply |

| Typical Quantities | 1–100 per iteration | Hundreds to hundreds of thousands |

| Setup and Tooling | Flexible, modular, low investment | Optimized, dedicated, higher investment |

| Programming Focus | Speed, agility, minimum programming time | Cycle time and tool life optimization |

| Material Strategy | Mix of proxy and final materials | Defined production materials with stable supply |

| Tolerances and GD&T | Focus on key features, flexibility for changes | Stable, fully defined tolerance schemes |

| Surface Finish | Functional surfaces prioritized | Consistent cosmetic and functional finishes |

| Lead Time | Short turnaround, days to weeks | Planned lead time integrated into supply chain |

| Cost per Part | High, dominated by setup and engineering | Optimized, with costs spread over volume |

| Quality Control | Focused, project-specific inspection | Formal quality systems and documentation |

How to Choose Between CNC Prototyping and Production Machining

In practice, many projects use a combination of prototyping and production machining at different stages. Choosing the appropriate approach depends on design maturity, target volumes, technical risk, and commercial objectives.

Key questions to consider include:

- Is the design stable or likely to change significantly after testing?

- What quantities are needed in the next phase (single prototypes, small pilot runs, or full production)?

- Do parts need to be made from the exact production material for testing?

- Which dimensions and features are critical to performance and must be controlled already at the prototype stage?

- What lead time constraints exist for testing, validation, or market launch?

For early development, CNC prototyping provides the flexibility to iterate quickly and discover design issues at low volume. As demand increases and the design stabilizes, production machining strategies can be introduced gradually through pre-production runs and process optimization, eventually resulting in full-scale, cost-effective manufacturing.

Conclusion

CNC prototyping and production machining are complementary phases in the lifecycle of machined parts. Prototyping emphasizes flexibility, rapid iteration and technical learning, while production machining focuses on repeatable quality, cost efficiency, and reliable supply.

By understanding how these approaches differ in setup, programming, material strategy, tolerances, surface finish, lead time, cost and quality control, engineers and buyers can plan an effective path from initial design to stable production. Aligning design decisions with manufacturability considerations early reduces the effort required to transition from prototype parts to fully validated production processes.

FAQ: CNC Prototyping and Production Machining

When should I switch from CNC prototyping to production machining?

The switch is appropriate when the design is functionally validated, engineering changes become infrequent, and you have predictable demand for repeated quantities. A typical sequence is: several prototype iterations for design and functional testing, one or more pre-production or pilot runs to validate the manufacturing process and quality controls, and then release to full production machining once performance, quality, and supply requirements are consistently met.

Can the same supplier handle both prototyping and production machining?

Yes, many CNC machining suppliers offer both services. This can simplify the transition from prototype to production because process knowledge, tooling experience, and fixture concepts are already in place. When evaluating a supplier for both phases, review their capacity for quick-turn prototypes, their experience in developing stable production processes, and their quality management system to ensure they can support your project throughout its lifecycle.

Do prototype parts need to use the final production material?

It depends on the purpose of the prototype. For basic form, fit and assembly checks, approximate materials are often sufficient and can reduce cost and lead time. For functional, mechanical, thermal, or durability testing, using the exact production material is strongly recommended because behavior can differ significantly between alloys or polymer grades. When regulatory approvals are involved, prototypes used for testing may be required to match production materials and processing conditions.

Why are prototype parts often more expensive per unit than production parts?

Prototype parts include one-time activities such as programming, engineering review, fixturing and setup that are spread over very few pieces. Machine time may be less optimized, materials are often purchased in smaller quantities, and changeovers are more frequent. In production machining, these fixed costs are amortized across larger volumes, and cycle times as well as scrap rates are optimized, reducing the cost per unit.

What information should I provide when requesting CNC prototype parts?

For CNC prototypes, provide 3D CAD files and drawings if available, indicate critical dimensions and tolerances, specify material and any acceptable alternatives, define surface finish and cosmetic requirements, list the required quantity and target lead time, and describe how the parts will be used (fit check, functional test, or demonstration). This helps the machining supplier choose appropriate setups, materials, and inspection levels for your development stage.