Titanium alloys are commonly categorized into alpha (α), beta (β), and alpha+beta (α+β) systems according to their phase composition and microstructure at room temperature. This phase-based classification strongly influences mechanical properties, corrosion resistance, weldability and suitability for different engineering applications. Understanding the distinctions between α, β, and α+β titanium alloys is fundamental for alloy selection, component design and process optimization.

Fundamentals of Titanium Phases and Phase Stabilizers

Pure titanium exhibits an allotropic transformation: it has a hexagonal close-packed (hcp) α phase at lower temperatures and transforms to a body-centered cubic (bcc) β phase at higher temperatures. The transformation temperature between α and β for unalloyed titanium is called the beta transus and is approximately 882 °C, depending on impurity content.

Alpha (hcp) and Beta (bcc) Crystal Structures

The two fundamental phases of titanium differ in crystal structure and thus in deformation behavior and solubility of alloying elements.

- α phase: hcp structure; limited slip systems; high strength at elevated temperatures; good creep resistance; generally lower formability at room temperature than β.

- β phase: bcc structure; more slip systems; good room-temperature formability; strong sensitivity to heat treatment; can be metastable at room temperature depending on composition and cooling rate.

The fraction and morphology of α and β phases present at room temperature define whether an alloy is classified as α, near-α, α+β, metastable β, or stable β.

Alpha and Beta Stabilizing Elements

Alloying elements in titanium either raise or lower the beta transus temperature and stabilize α or β phase respectively.

| Type | Elements | Effect on Ti phases |

|---|---|---|

| Alpha stabilizers | Al, O, N, C | Raise β transus, expand α field, strengthen α solution |

| Neutral elements | Zr, Sn | Do not strongly shift α/β balance, solid-solution strengthening |

| Beta stabilizers (isomorphous) | Mo, V, Nb, Ta, W | Lower β transus, stabilize β over wide range, often fully soluble in β |

| Beta stabilizers (eutectoid) | Fe, Cr, Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Si | Lower β transus; may form intermetallic phases on cooling/aging |

By combining these elements, alloy designers tailor titanium alloys towards predominantly α, predominantly β, or a balanced α+β microstructure at service temperature.

Classification of Titanium Alloys by Phase Constitution

Engineering titanium alloys are often grouped into five practical classes, but for many design and manufacturing decisions, three main categories are most relevant: α, β, and α+β. Within these categories, compositions and processing routes are chosen to control the relative fraction, morphology, and distribution of phases.

Alpha (α) and Near-Alpha Titanium Alloys

Alpha titanium alloys contain primarily α phase with limited β phase at room temperature, while near-α alloys contain a small but useful amount of β to improve processing characteristics. These alloys rely heavily on aluminum and interstitials (oxygen, nitrogen) as α stabilizers, with possible additions of neutral elements such as zirconium and tin.

Alpha+Beta (α+β) Titanium Alloys

Alpha+beta titanium alloys exhibit both α and β phases at room temperature, with the relative fraction dependent on composition and heat treatment. They represent the most widely used class of titanium alloys in aerospace and general engineering, offering a balanced combination of strength, ductility and forgeability.

Metastable Beta (β) and Stable Beta Titanium Alloys

Beta titanium alloys are designed so that β phase remains stable or metastable at room temperature through the addition of sufficient β-stabilizing elements. Metastable β alloys can transform to α or α-related phases via heat treatment or deformation, whereas stable β alloys retain the β structure across a wide temperature range. Both forms generally offer high strength and good formability but require precise processing control to achieve desired properties.

Chemical Composition Ranges and Typical Grades

The choice of alloying elements and their concentrations determines whether the alloy is α, β, or α+β. Certain grades have become standards due to their balanced properties and industrial track record.

Representative Alloy Compositions

The table below lists typical composition ranges for widely used alloys from each category. Values are approximate and given in weight percent.

| Alloy type | Common designation | Typical main alloying elements (wt%) | Key features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercially pure (CP, α) | Grade 1–4 Ti | Ti with O ~0.18–0.40, Fe <0.30, other impurities low | High corrosion resistance, low to moderate strength, good formability |

| Near-α | Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo (Ti-6242) | Al ~6, Sn ~2, Zr ~4, Mo ~2, with small Si | High-temperature strength, good creep resistance, aerospace compressor components |

| α+β (workhorse) | Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) | Al 5.5–6.75, V 3.5–4.5, Fe ≤0.40, O ≤0.20 | Balanced strength, ductility, weldability; very widespread aerospace and industrial use |

| α+β (moderate strength) | Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Grade 23) | Similar to Ti-6Al-4V but with reduced O and Fe | Improved toughness and fracture toughness; widely used in biomedical implants |

| α+β (higher strength) | Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-6Mo (Ti-6246) | Al ~6, Sn ~2, Zr ~4, Mo ~6 | Higher strength than Ti-6Al-4V; suitable for highly loaded aerospace parts |

| Metastable β | Ti-10V-2Fe-3Al (Ti-10-2-3) | V ~10, Fe ~2, Al ~3 | High strength after heat treatment, good hardenability, used in landing gear and structures |

| Metastable β | Ti-15V-3Cr-3Sn-3Al (Ti-15-3) | V 15, Cr 3, Sn 3, Al 3 | Good cold formability in solution-treated condition; high strength after aging |

| Metastable β (biomedical) | Ti-13Nb-13Zr | Nb 13, Zr 13 | Lower elastic modulus, good biocompatibility for implants |

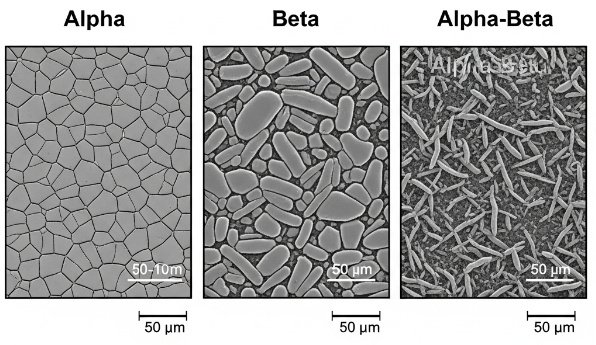

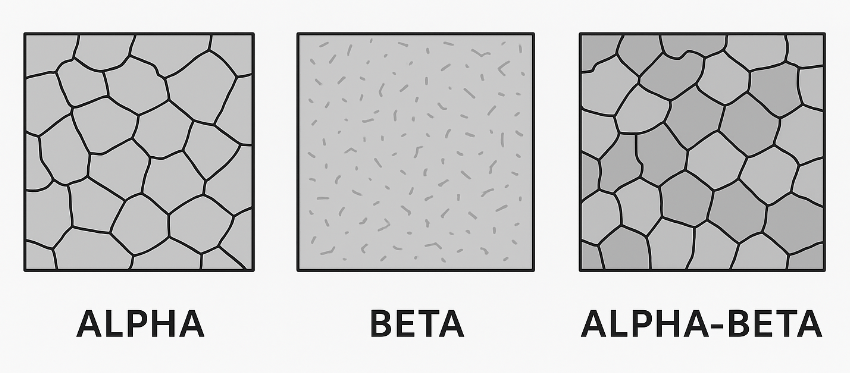

Microstructural Characteristics by Alloy Type

Microstructure is a critical link between composition, processing and performance. Each titanium alloy class has characteristic α and β morphologies, which can be tailored by thermomechanical processing.

Microstructure of Alpha Alloys

Alpha and near-α alloys show predominantly equiaxed α grains at room temperature, often with a small fraction of β located at grain boundaries in near-α variants. Typical features include:

- Equiaxed α grains: relatively uniform grain size after appropriate thermomechanical processing, contributing to good fatigue strength and toughness.

- Grain-boundary β in near-α alloys: thin films or small particles at α grain boundaries, improving workability and enabling some heat-treatment response.

- Limited microstructural variability: α alloys are comparatively less responsive to heat treatment than α+β and β alloys; property tuning is more dependent on composition and working history.

Microstructure of Alpha+Beta Alloys

α+β alloys can exhibit a wide range of microstructures depending on processing above or below the beta transus and the applied cooling rate. Common microstructural types include:

Equiaxed α+β: Produced by forging or rolling in the α+β region followed by air cooling. The microstructure contains primary equiaxed α grains with β (and transformed β) between them, offering a good balance of strength and toughness.

Bi-modal (duplex): Contains primary α in a transformed β matrix (fine α within prior β grains). Achieved by solution treatment in the upper α+β region then controlled cooling. This structure combines high strength with acceptable fracture toughness.

Lath or Widmanstätten (basketweave): Formed by solution treating above β transus followed by cooling, causing β to transform to colonies of α laths. This structure can provide improved fracture toughness and crack growth resistance, but may reduce ductility compared to equiaxed structures.

Microstructure of Beta Alloys

Metastable β alloys are typically processed in the β phase field and then quenched to retain β at room temperature. Subsequent aging treatments promote precipitation of fine α or α-related phases in the β matrix. Typical microstructural features include:

Solution-treated condition:

- Single-phase β with relatively uniform grain size and high formability.

- Retained metastable β structure that is supersaturated with alloying elements.

Aged condition:

- Fine α precipitates within β grains, often with controlled size and distribution to obtain high strength.

- Possibility of grain-boundary α or intermetallic phases if aging conditions are not optimized, which may reduce ductility and toughness.

Stable β alloys maintain the β structure at room temperature without significant α precipitation during conventional heat treatments, though specialized processes can still modify mechanical response.

Mechanical Properties of α, β and α+β Titanium Alloys

The phase constitution and microstructure strongly influence yield strength, ultimate tensile strength, ductility, fatigue resistance, creep performance, and elastic modulus. While elastic modulus varies only moderately across titanium alloys, strength and ductility can vary widely.

General Property Trends by Alloy Class

Typical room-temperature mechanical property ranges (approximate, for wrought products in commonly used conditions):

- α and near-α alloys: yield strength about 400–900 MPa, good creep resistance, good weldability, moderate fatigue strength.

- α+β alloys: yield strength about 800–1200 MPa (depending on grade and heat treatment), good combination of strength and ductility, broad applicability.

- Metastable β alloys: yield strength up to 1300–1500 MPa after aging, high hardenability, good formability in solution-treated condition but often reduced ductility in peak-aged condition.

Strength and Ductility

Alpha alloys gain strength mainly from solid-solution strengthening via aluminum and interstitials; their microstructure changes moderately with processing. Consequently, they offer stable properties across a range of conditions but have limited maximum strength compared to β-rich alloys.

α+β alloys can be significantly strengthened by microstructural control, for example adjusting the amount of primary α and transformed β or refining α laths. Heat treatments below or just above the beta transus allow designers to trade ductility for strength or vice versa.

Metastable β alloys allow the most extensive strength variation via aging; fine α precipitation in β yields high strength at the expense of ductility. Careful selection of aging times and temperatures can target specific combinations of tensile and toughness properties.

Fatigue and Fracture Behavior

Fatigue performance of titanium alloys depends on microstructure type, surface condition, and environment.

Alpha and near-α alloys with equiaxed α often show good high-cycle fatigue performance and high fracture toughness. Their relative insensitivity to heat treatment simplifies process control for fatigue-critical components.

α+β alloys like Ti-6Al-4V can achieve a favorable fatigue strength-to-density ratio, particularly when processed to a refined bi-modal or equiaxed microstructure and when surface integrity is carefully controlled. For high-cycle fatigue, elimination of surface defects and control of inclusions are essential.

Metastable β alloys, especially in high-strength conditions, can be more sensitive to defects and stress concentrations. Optimized aging and defect control are required to ensure fatigue reliability at very high strength levels.

Physical and Chemical Properties

Despite differences in alloying and microstructure, titanium alloys share certain core physical and chemical characteristics, which are modified in detail by phase constitution.

Density and Elastic Modulus

Most titanium alloys have density between 4.4 and 4.7 g/cm³, significantly lower than steels and nickel-based superalloys. Differences in alloying element content (particularly heavy β stabilizers such as Mo or W) can slightly increase density in β alloys compared with α and α+β alloys.

The elastic modulus of conventional titanium alloys lies in the range of about 100–120 GPa at room temperature. Metastable β alloys developed for biomedical use can exhibit lower moduli (for example 70–90 GPa) due to β stabilization and tailored microstructures, providing better stiffness compatibility with bone.

Corrosion Resistance and Oxidation

Titanium owes its corrosion resistance to a thin, adherent and stable oxide film that forms spontaneously on exposure to oxygen-containing environments. This film provides excellent resistance in many chloride-containing solutions and oxidizing acids.

Alpha and near-α alloys, especially commercially pure grades, are often selected where corrosion resistance is critical, for example in chemical processing, marine environments and medical devices. They have minimal alloying additions that might compromise passivity.

α+β and β alloys retain good corrosion resistance in most environments, but higher levels of alloying elements can influence behavior in specific media. For biomedical and chemical applications, compositions are selected to avoid elements detrimental to biocompatibility or corrosion performance.

At elevated temperatures, oxidation resistance becomes more important. Near-α alloys with aluminum and tin additions provide good oxidation and creep resistance up to intermediate temperatures, making them suitable for compressor components and similar parts.

Processability, Heat Treatment and Weldability

Processing routes for titanium alloys include forging, rolling, machining, welding and various heat treatments. The capability and constraints differ between α, α+β and β alloys and must be considered in component and process design.

Hot and Cold Workability

Alpha alloys have limited cold formability compared to β-rich alloys due to their hcp structure, but they can be hot worked in the α or α+β temperature range with appropriate control of temperature and strain rate. Near-α alloys may be somewhat more workable due to a small β fraction.

α+β alloys like Ti-6Al-4V show good forgeability and can be processed over a relatively wide temperature range. Forging and rolling in the α+β domain allow fine control over microstructure and properties.

Metastable β alloys exhibit excellent hot and cold workability in the solution-treated β condition, benefiting from the bcc structure. This higher formability is often exploited to produce complex shapes before final aging to achieve high strength.

Heat Treatment Response

Heat treatment is a key tool for tailoring microstructure, particularly in α+β and β alloys.

Alpha alloys: Heat treatment has limited effect on mechanical properties; operations such as stress relief and annealing are used mainly to stabilize microstructure and relieve residual stresses. Solution treatment and aging are less effective, as there is minimal β phase to transform.

α+β alloys: Common heat treatments include:

- Annealing in the α+β region to obtain equiaxed or bi-modal microstructures.

- Solution treatment below or just above the beta transus followed by controlled cooling to adjust primary α content and α lath morphology.

- Aging treatments to refine secondary α precipitates in β, enhancing strength.

Metastable β alloys: Heat treatment is highly effective:

- Solution treatment in the β region followed by rapid cooling to retain single-phase β.

- Aging at moderate temperatures to precipitate fine α, achieving high strength.

- Overaging to coarsen precipitates when higher toughness or ductility is required.

Weldability and Joining

Alpha and near-α alloys generally possess good weldability, especially in inert gas shielded processes. Their microstructure and properties are less drastically affected by welding thermal cycles than β-rich alloys.

α+β alloys, notably Ti-6Al-4V, are widely welded using gas tungsten arc welding, laser welding and friction welding techniques. The weld zone and heat-affected zone may develop transformed β microstructures with different properties from the base material, so post-weld heat treatment is sometimes used to restore a balanced microstructure.

Metastable β alloys can be welded but demand careful control of procedure and post-weld heat treatment. Rapid cooling from the weld can produce non-equilibrium microstructures, and improper post-weld aging can introduce brittle phases. For critical structures, welding procedures are rigorously qualified to ensure acceptable toughness and fatigue performance.

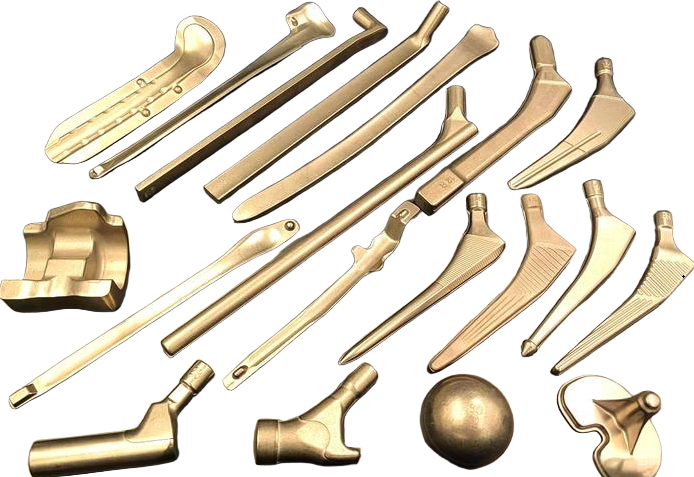

Applications of α, β and α+β Titanium Alloys

The distinct property sets of each alloy type make them suitable for specific categories of applications. Selection is based on requirements such as temperature capability, strength level, fabrication route, corrosion resistance and cost.

Applications of Alpha and Near-Alpha Alloys

Alpha and near-α alloys are used where corrosion resistance, high-temperature strength and weldability are more important than maximum room-temperature strength.

Typical applications include:

- Chemical processing equipment: tanks, heat exchangers and piping in chloride and oxidizing environments.

- Marine hardware and desalination components: due to resistance to seawater corrosion and biofouling.

- Aerospace compressor components: near-α alloys with good creep and oxidation resistance operate at elevated temperatures in gas turbine engines.

- Biomedical devices: certain commercially pure grades are used for dental implants, surgical instruments and some prostheses.

Applications of Alpha+Beta Alloys

α+β alloys are the most broadly used titanium alloys and represent a standard choice for many high-performance engineering structures.

Examples include:

- Aerospace airframe and engine components: Ti-6Al-4V is widely used for structural parts, fasteners, discs and blades operating at moderate temperatures.

- Automotive and motorsport: connecting rods, valves, springs and structural components requiring high strength-to-weight ratio.

- Biomedical implants: Ti-6Al-4V ELI is extensively used for hip stems, knee components and spinal fixation devices due to its biocompatibility and mechanical performance.

- Industrial equipment: high-strength components in power generation, offshore structures and high-performance sporting goods.

Applications of Beta and Metastable Beta Alloys

Metastable β alloys are chosen when very high strength, good formability in the solution-treated condition or modified elastic modulus are required.

Typical uses include:

- Aerospace landing gear and high-strength structural parts: exploiting high strength and good fracture toughness after aging.

- Springs and fasteners: where high strength and good fatigue performance are crucial.

- Biomedical implants: β alloys with niobium, zirconium and tantalum can offer lower elastic modulus closer to that of bone, reducing stress shielding in load-bearing implants.

Selection Considerations and Practical Issues

Choosing between α, β and α+β titanium alloys requires a systematic assessment of design requirements, manufacturing constraints and service environment conditions. Certain recurring issues influence alloy selection and process planning.

Balancing Strength, Ductility and Manufacturability

High-strength β alloys may appear attractive for weight reduction, but the increase in strength often brings stricter control requirements in forging, heat treatment and welding. For structures where extreme strength is not mandatory, α+β alloys can provide a better compromise between mechanical performance and process robustness.

Alpha alloys, while simpler to process from a microstructural standpoint, may not meet very high strength targets. They may, however, exceed α+β and β alloys in creep resistance and corrosion performance for certain conditions, making them advantageous for specific high-temperature or aggressive environments.

Consistency of Microstructure and Properties

For α+β and β alloys, achieving consistent microstructure across large forgings or thick sections is technically demanding. Through-thickness cooling rates, heat-treatment uniformity and deformation history can all affect the distribution of α and β phases, which in turn influence fatigue and fracture behavior.

In safety-critical applications such as aerospace structures, process windows are carefully defined to control microstructure (for example, the fraction of primary α or the size of α laths). These controls help ensure that mechanical properties remain within specified limits throughout the component volume.

Joining-Related Considerations

Different alloy classes respond differently to welding, brazing and mechanical joining. Alpha and near-α alloys are relatively forgiving, while β-rich alloys are more sensitive to heat input and cooling rates. When dissimilar welding (for example, α+β to β alloy) is required, filler selection and post-weld heat treatment must be designed to prevent brittle microstructures at the interface.

FAQ on Alpha, Beta and Alpha+Beta Titanium Alloys

What is the main difference between alpha and beta titanium alloys?

Alpha titanium alloys are dominated by the hexagonal close-packed (α) phase at room temperature and are stabilized by elements such as aluminum and oxygen. They provide good corrosion resistance, good weldability and reliable performance at elevated temperatures, but their maximum achievable strength and room-temperature formability are limited compared to β-rich alloys. Beta alloys are dominated by the body-centered cubic (β) phase, stabilized by elements like molybdenum, vanadium and niobium. They offer excellent formability in the solution-treated condition and can reach very high strength after aging, but they require tighter control of heat treatment and welding procedures.

When should an alpha+beta alloy like Ti-6Al-4V be selected?

An α+β alloy such as Ti-6Al-4V is typically chosen when a balanced combination of strength, ductility, fatigue performance, corrosion resistance and manufacturability is required. It is suitable for a wide range of structural components in aerospace, industrial and biomedical applications. The alloy can be forged and machined with well-established procedures, and its microstructure can be adjusted through heat treatment to tailor properties. It is particularly appropriate when strength levels higher than those of commercially pure titanium are needed, but the complexity and sensitivity of fully β alloys are not justified.

Do all beta titanium alloys have a lower elastic modulus than alpha+beta alloys?

Not all β titanium alloys have a lower elastic modulus than α+β alloys. Conventional high-strength β alloys often have a modulus comparable to or only slightly lower than that of α+β alloys, typically around 100–120 GPa. Some specially designed metastable β alloys for biomedical applications use particular combinations of niobium, zirconium and tantalum to achieve a significantly reduced modulus, for example 70–90 GPa. Therefore, a lower modulus is not an inherent property of all β alloys but a feature of specific compositions and microstructures.

Can alpha, beta and alpha+beta titanium alloys be welded to each other?

In many cases, α, β and α+β titanium alloys can be welded to each other using appropriate shielding and procedures, but metallurgical compatibility and post-weld properties must be evaluated carefully. Welding dissimilar alloys can lead to non-uniform microstructures across the weld zone and heat-affected zone, with corresponding variations in strength, ductility and fatigue behavior. For critical applications, weld procedure qualification, filler metal selection and post-weld heat treatment are defined to ensure that the joint properties match the design requirements and do not introduce weak regions in the structure.