Precision machining is the controlled removal of material from a workpiece to achieve tight dimensional tolerances, demanding surface finishes, and repeatable quality. It combines machine tools, cutting tools, workholding, metrology, and process control to produce components that meet strict geometric and functional requirements.

What Is Precision Machining

Precision machining is a subset of machining where the goal is to achieve close tolerances and consistent dimensional accuracy across batches or throughout a product’s life cycle. This typically involves CNC (computer numerical control) equipment, advanced tooling, and rigorous inspection methods.

Key objectives include:

- Maintaining dimensional accuracy over critical features and mating interfaces

- Achieving specific surface roughness and avoiding defects such as burrs or chatter marks

- Controlling geometric relationships such as flatness, perpendicularity, and concentricity

- Ensuring repeatability and stability of the process over time and across batches

Core Types of Precision Machining Processes

Precision machining encompasses a range of subtractive processes. Each process has distinct capabilities in terms of tolerance, surface finish, geometry, and material compatibility.

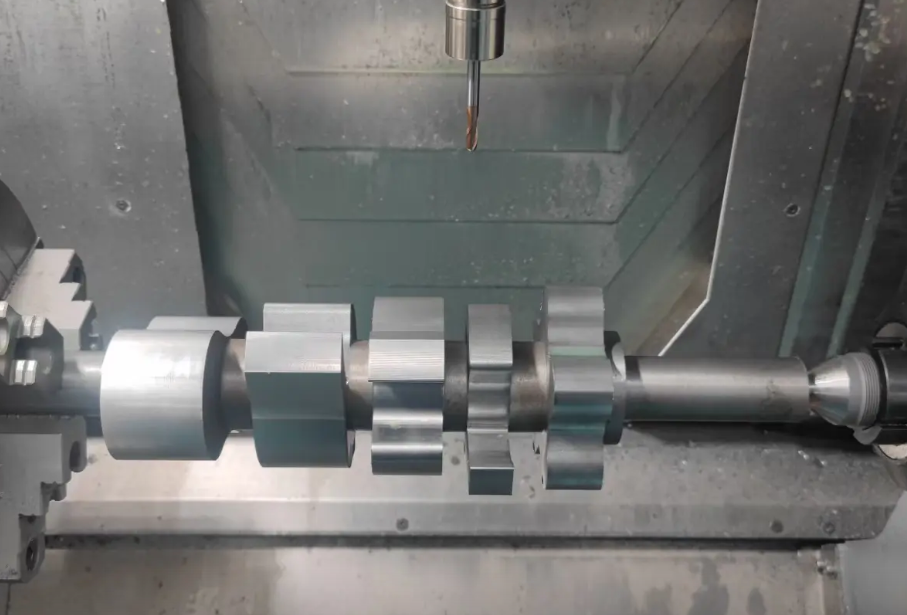

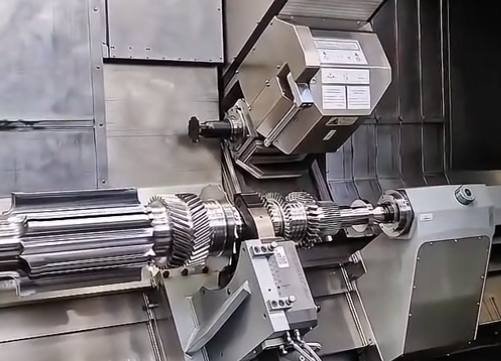

Turning

Turning is a machining process where a rotating workpiece is cut by a stationary or controlled moving tool, typically on a lathe. It is ideal for rotationally symmetric parts such as shafts, bushings, and rings.

Typical capabilities:

- Tolerances: commonly ±0.01 mm, high-precision lathes can achieve ±0.002–0.005 mm on critical diameters

- Surface finish: Ra ~0.8–3.2 µm in standard turning, Ra <0.4 µm with fine tooling and finishing passes

- Features: external and internal diameters, grooves, threads, tapers, radii, and undercuts

Common variants include:

CNC Turning: Uses CNC lathes or turning centers with programmable axes (e.g., X, Z, often Y and C). Capable of complex profiles and integrated milling operations in a single setup.

Swiss-Type Turning: Ideal for long, slender parts requiring tight tolerances and excellent straightness. The workpiece is supported close to the cutting zone by a guide bushing, improving rigidity and reducing deflection.

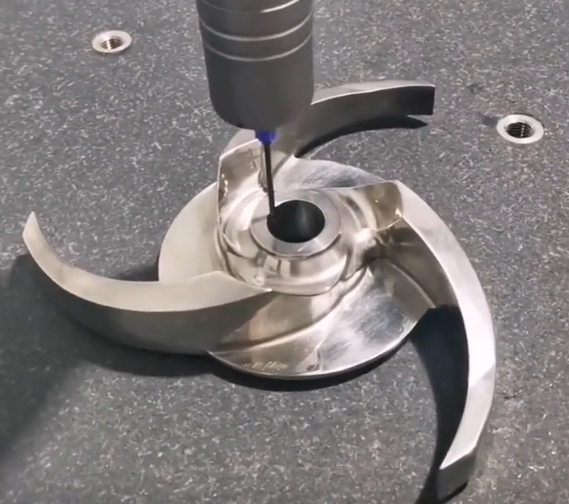

Milling

Milling removes material using a rotating multi-point cutting tool. The workpiece and tool move relative to each other along multiple axes, allowing complex 2D and 3D geometries.

Typical capabilities:

- Tolerances: ±0.01 mm is common; precision milling can reach ±0.005 mm or better on selected features

- Surface finish: Ra ~0.4–3.2 µm depending on tool, feed, and finishing strategy

- Features: pockets, slots, profiles, 3D contours, complex surfaces, and planar faces

Milling machines include 3-axis vertical and horizontal machining centers as well as 4- and 5-axis systems, which can machine complex shapes in fewer setups and maintain better positional accuracy between features.

Drilling, Boring, and Reaming

Drilling creates round holes using a rotating drill bit. For precision machining, holes typically require additional operations:

Boring: Enlarges and trues existing holes to achieve precise diameters and location accuracy, often reaching tolerances of ±0.005 mm or better on critical bores.

Reaming: Produces high-precision hole diameters with improved surface finish, commonly achieving H7 or tighter fits depending on tool and material.

Applications include bearing seats, alignment holes, fluid passages, and precision dowel locations that must maintain tight positional and size constraints.

Grinding

Grinding uses a rotating abrasive wheel to achieve very fine finishes and high dimensional accuracy. It is often used as a finishing process after turning or milling.

Capabilities:

- Tolerances: ±0.001–0.005 mm on diameter or flatness, depending on workpiece size and setup

- Surface finish: Ra <0.2 µm, with specialized processes achieving Ra <0.05 µm

- Materials: hardened steels, carbides, ceramics, and other hard materials

Common variants include surface grinding, cylindrical grinding (OD/ID), centerless grinding, and form grinding, each tuned for a particular geometry or production volume.

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

EDM removes material through controlled electrical discharges between an electrode and the workpiece, submerged in a dielectric fluid. It is suitable for conductive materials and complex or delicate geometries that are difficult or impossible to machine with conventional cutting tools.

Types:

Sinker EDM: Uses a shaped electrode to form cavities and intricate 3D features, often in hard tool steels for molds and dies.

Wire EDM: Uses a continuously fed wire electrode to cut precise profiles through the workpiece, functioning like a contour saw with high accuracy.

Capabilities commonly include tolerances of ±0.002–0.005 mm and sharp internal corners, with minimal mechanical stresses induced in the part.

Laser and Waterjet Machining

Laser machining uses focused laser beams to cut or ablate material. It can be used for micro features, fine kerfs, and delicate components. Waterjet machining uses a high-pressure jet of water, often with abrasive, to cut a wide variety of materials without significant heat-affected zones.

In many precision machining workflows, laser and waterjet are used for near-net-shape cutting, followed by secondary precision milling, grinding, or EDM to achieve final tolerances.

Micromachining

Micromachining refers to machining of very small features or parts, often with dimensions below 1 mm. It uses miniaturized tools and specialized machine tools with high-speed spindles, high-resolution drives, and precise thermal control.

This is used for microfluidic devices, watch components, miniature medical devices, and precision sensors, where feature sizes may be tens of microns and tolerance bands can be in the single-micron range.

Materials for Precision Machining

Material selection strongly influences tool life, achievable tolerances, and surface finish. Different materials require optimized cutting parameters, tooling, and coolant strategies.

| Material Category | Typical Grades/Examples | Key Characteristics | Typical Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon & Alloy Steels | 1045, 4140, 4340, 1215 | Good strength, heat-treatable, wide availability; machinability varies with composition and hardness | Shafts, gears, fasteners, structural components |

| Stainless Steels | 303, 304, 316, 17-4PH, 15-5PH | Corrosion resistance, moderate to high strength; some grades work-harden and require careful cutting strategy | Medical parts, food processing equipment, marine hardware |

| Tool Steels | D2, A2, H13, M2 | High hardness and wear resistance after heat treatment; challenging to machine in hardened state | Molds, dies, cutting tools, wear components |

| Aluminum Alloys | 6061, 6082, 7075, 2024 | Excellent machinability, low density, good strength-to-weight ratio, good thermal conductivity | Aerospace structures, enclosures, fixtures, automotive parts |

| Titanium Alloys | Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5), Grade 2 | High strength, low density, excellent corrosion resistance; low thermal conductivity and tendency to gall | Aerospace, medical implants, high-performance automotive |

| Nickel-Based Alloys | Inconel 718, Hastelloy C-276 | High temperature strength and corrosion resistance; difficult-to-cut, requiring specialized tooling | Turbine components, chemical processing equipment |

| Copper & Copper Alloys | C110, C145, brass, bronze | High electrical and thermal conductivity; some alloys are very free-machining | Electrical contacts, heat exchangers, precision fittings |

| Engineering Plastics | PEEK, PTFE, POM (Delrin), nylon, UHMWPE | Low weight, insulation properties, chemical resistance; sensitive to heat buildup and deformation | Insulators, medical components, bearings, seals |

| Ceramics | Alumina, zirconia, silicon nitride | High hardness and wear resistance, high-temperature stability; mainly ground or EDM-machined | Wear parts, bearings, high-temperature components |

Material-Related Considerations

Different materials present different process considerations:

Hard materials such as hardened tool steels and ceramics often require grinding or EDM for final dimensions. Materials with poor thermal conductivity, such as titanium and nickel alloys, need careful heat management to avoid tool wear and dimensional distortion. Plastics and composites may require reduced cutting speeds and specialized tool geometries to prevent melting, tearing, or delamination.

Tolerances and Surface Finish in Precision Machining

Precision machining is defined by its ability to hold tight tolerances and achieve targeted surface finishes. Understanding tolerance classes and surface roughness metrics is essential when specifying or evaluating precision machining work.

Dimensional Tolerances

Dimensional tolerance describes the permissible variation in a linear dimension, angle, or geometric feature. Precision machining often works in the range of hundredths or thousandths of a millimeter for high-accuracy components.

Typical ranges by process and equipment sophistication include:

- General CNC machining: ±0.05–0.10 mm for non-critical features

- Precision CNC turning and milling: ±0.005–0.02 mm on critical features

- Grinding and high-precision finishing: ±0.001–0.005 mm on select dimensions

Capabilities depend heavily on machine condition, thermal stability, tooling, fixturing, and inspection methods.

Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T)

GD&T defines allowable variation for shape, orientation, location, and runout of features. It is widely used in precision machining because it communicates functional requirements more clearly than simple plus/minus dimensions.

Commonly controlled characteristics include:

Flatness, straightness, circularity, cylindricity, parallelism, perpendicularity, concentricity, position, and total runout. Precision machining processes must be capable not only of holding size but also of maintaining these geometric relationships, especially for mating assemblies and rotating components.

Surface Roughness

Surface roughness is usually expressed as Ra (arithmetical mean roughness) in micrometers (µm). Typical ranges in precision machining are:

| Process | Typical Ra Range (µm) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Rough Turning/Milling | 3.2–6.3 | Used for bulk material removal and non-critical features |

| Finish Turning/Milling | 0.8–3.2 | Suitable for many functional surfaces and general-purpose parts |

| Fine Turning/Skiving | 0.2–0.8 | Used where lower friction and better sealing are required |

| Grinding | 0.05–0.4 | Typical for bearing seats, sealing surfaces, and precision fits |

| Lapping/Honing | 0.01–0.1 | For very tight fits, hydraulic components, and sealing bores |

Workholding, Fixturing, and Setup

Workholding has a direct impact on achievable accuracy and repeatability. Even a highly accurate machine cannot produce consistent results if the workpiece is poorly supported or allowed to shift during machining.

Workholding Methods

Common methods include three- and four-jaw chucks, collets, vises, fixtures, vacuum chucks, and magnetic chucks. For precision work, features such as ground locating pins, precision bushings, and reference surfaces are used to control part location and orientation.

Key considerations:

- Minimizing deflection and vibration by ensuring rigid clamping and short overhangs

- Using datum structures in the workholding that correspond to functional datums in the drawing

- Balancing clamping forces to avoid part distortion, especially for thin-walled components

Setup and Datum Strategies

Precision machining often requires planning of setup sequences so that critical datums are established early and preserved through subsequent operations. Multi-axis and multi-tasking machines can reduce the number of setups, minimizing errors introduced by repeated re-clamping and re-referencing.

Cutting Tools and Tooling Systems

Tool selection and tool management strongly influence surface quality, dimensional accuracy, and cost. Tool geometry, substrate material, and coatings must be matched to the workpiece material and the operation.

Cutting Tool Materials

Common tool materials include high-speed steel (HSS), carbide, cermet, ceramics, polycrystalline diamond (PCD), and cubic boron nitride (CBN). Carbide is widely used in precision machining for its balance of hardness and toughness. PCD and CBN are applied in high-volume or hard-material applications where long tool life and excellent finish are required.

Tool Geometry and Coatings

Rake angle, clearance, nose radius, and edge preparation are tuned to control cutting forces, chip formation, and surface finish. Coatings such as TiN, TiAlN, and DLC improve wear resistance and reduce friction, which helps maintain consistent cutting conditions over the tool’s life.

Tool Holding and Runout Control

Collet chucks, hydraulic chucks, shrink-fit holders, and other high-precision toolholders are used to minimize runout and vibration. Low runout is essential for maintaining consistent hole size in drilling, reducing chatter in milling, and achieving uniform surface finishes.

Process Parameters and Machining Strategies

Precision machining requires careful selection of spindle speed, feed rate, depth of cut, coolant application, and toolpath strategy. The objective is to keep cutting conditions stable and predictable while avoiding excessive tool wear or part distortion.

Speed, Feed, and Depth of Cut

Cutting speed is typically expressed as surface speed (m/min or ft/min), feed as feed per tooth or feed per revolution, and depth of cut as radial and axial engagement. For high-precision finishing passes, smaller depths of cut and reduced feeds are used to minimize cutting forces and improve surface quality.

Coolant and Lubrication

Coolant removes heat and flushes chips away from the cutting zone, which protects both the tool and the workpiece. Cutting oils, water-soluble coolants, and minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) are selected based on material, operation, and cleanliness requirements. For some materials and micro-scale features, dry machining is used with optimized tool coatings and geometries.

Toolpath and Cut Direction

Toolpaths are designed not only to remove material efficiently but also to control part deflection and residual stress. Strategies such as climb milling for better surface finish and constant engagement toolpaths for stable load can help maintain precision across complex geometries.

Inspection and Metrology in Precision Machining

Inspection methods verify that machined components meet dimensional, geometric, and surface specifications. In precision machining, metrology is tightly integrated into production to maintain process capability.

Measuring Equipment

Common instruments include:

- Calipers and micrometers for basic dimensions

- Height gauges and surface plates for precise linear and angular measurements

- CMM (Coordinate Measuring Machines) for complex geometries and GD&T features

- Profile projectors and optical comparators for silhouette and profile analysis

- Surface roughness testers for Ra, Rz, and other roughness parameters

In-Process and Final Inspection

In-process inspection checks critical features during machining to detect deviations early. Probing systems integrated into CNC machines can measure workpiece features and adjust offsets automatically. Final inspection verifies that all requirements are met before parts are released, often with documented inspection reports.

Precision Machining Applications by Industry

Precision machining supports a wide range of industries that require reliable, high-accuracy components. Each sector has distinct material preferences, tolerance needs, and regulatory constraints.

Aerospace and Defense

Aerospace components demand tight tolerances and high performance under demanding conditions such as high temperatures and cyclic loads. Typical applications include engine components, structural parts, actuators, and fluid system fittings.

Common characteristics:

- Use of aluminum, titanium, high-strength steels, and nickel-based superalloys

- Strict adherence to quality standards and documentation requirements

- Emphasis on weight reduction and reliability

Automotive and Motorsports

Precision machining is used for engine parts, transmission components, suspension parts, braking systems, and various housings. High-volume production in automotive applications requires stable and repeatable machining processes, often with dedicated tooling and fixtures.

Critical characteristics include consistent dimensional control for interchangeability, balanced rotating components, and surfaces that support low friction and controlled wear.

Medical Devices and Implants

Medical applications require biocompatible materials, traceability, and strict regulatory compliance. Precision machining supports orthopedic implants, surgical instruments, dental components, and device housings.

Common materials are titanium, cobalt-chrome, stainless steels, and engineering plastics like PEEK and UHMWPE. Surface finish and cleanliness are tightly controlled to support sterility and patient safety.

Electronics and Semiconductor Support

Precision machining provides fixtures, housings, heat sinks, and vacuum components for electronics and semiconductor manufacturing. Dimensional stability, cleanliness, and specific surface finishes are often critical to ensure proper function and avoid contamination.

Industrial Machinery and Tooling

Machine components, gears, spindles, hydraulic components, molds, and dies rely on precision machining to achieve performance and longevity. Tool steels and hardened alloys are commonly used, requiring grinding and EDM to reach final dimensions.

Energy and Power Generation

Precision machined parts appear in turbines, compressors, pumps, valves, and high-pressure fittings for power plants, oil and gas processing, and renewable energy equipment. Materials must withstand elevated temperatures, pressure, and corrosive environments while maintaining precise fit and performance.

Issues and Practical Considerations

Users of precision machining services often encounter several practical issues that must be addressed in planning and execution.

Dimensional Stability of Parts

Thin-walled parts, large flat surfaces, and slender shafts may distort during machining due to residual stress release, cutting forces, or thermal gradients. To mitigate this, stress-relief heat treatments, balanced material removal strategies, and controlled clamping pressure are applied. Multiple roughing and finishing stages may be used, allowing the material to stabilize between operations.

Cost and Lead Time Versus Tolerance Requirements

Tight tolerances and fine surface finishes increase machining time, tooling costs, and inspection complexity. Specifying tolerances tighter than functionally necessary can lead to higher part cost and longer lead times. A common approach is to define tolerance bands based on functional requirements and to reserve the tightest values for truly critical features.

Material Machinability

Some high-performance materials such as titanium alloys, nickel superalloys, and hardened steels are inherently more difficult to machine. They lead to higher tool wear and may require specialized tooling and optimized process parameters. This influences both cost and achievable cycle times and must be considered during design and material selection.

Design Considerations for Precision Machined Parts

Effective precision machining begins at the design stage. Features, tolerances, and material choices should be aligned with known machining capabilities to avoid unnecessary complications and costs.

Feature Geometry

Designers can facilitate precision machining by ensuring sufficient tool access, avoiding extremely deep and narrow cavities, and specifying radius values compatible with available tool diameters. Chamfers and generous radii can reduce stress concentration and improve machinability.

Tolerancing Strategy

Using GD&T to relate features to functional datums helps ensure that parts assemble and operate correctly. Functional fits (clearance, transition, interference) should be defined using standardized fit systems where applicable. Non-critical features can be assigned looser tolerances to reduce machining and inspection effort.

Material and Surface Treatment

Heat treatments, surface coatings, and surface texturing can affect dimensional stability and surface finish. In precision machining workflows, these processes are typically scheduled in a sequence that allows for any dimensional changes to be corrected or accommodated. For example, finishing operations are often performed after heat treatment and coating if the processes affect critical dimensions.

Typical Workflow for Precision Machining Projects

Precision machining projects generally follow a systematic workflow to ensure repeatable quality and efficient production.

1) Requirement Definition and Drawing Review

The process begins by analyzing technical drawings or 3D models, including tolerances, GD&T requirements, materials, and surface finish callouts. Functional datums are identified, and any ambiguous or conflicting specifications are resolved.

2) Process Planning

Next, machinists and process engineers select machine tools, cutting tools, fixtures, and inspection methods. They determine the sequence of operations, roughing and finishing strategies, and in-process inspection points.

3) Programming and Setup

CNC programs are created and validated. Machines are set up with the specified tools and fixtures, and reference datums are established. Trial runs may be performed to verify that the process can achieve the required tolerances and surface finishes.

4) Production and In-Process Inspection

Parts are produced according to the defined process. In-process measurements verify critical features and compensate for tool wear or thermal drift when necessary. Any deviations trigger analysis and corrective action.

5) Final Inspection and Documentation

Finished parts undergo final inspection using appropriate metrology tools. Results are documented, especially for industries that require traceability and formal inspection reports. Parts are then packaged and protected in a way that prevents damage to critical surfaces.

FAQ

What is precision machining?

Precision machining is a manufacturing process that uses CNC machines and advanced tooling to produce parts with very tight tolerances, high accuracy, and excellent surface finishes for critical applications.

What are the main types of precision machining?

The main types include CNC milling, CNC turning, 5-axis machining, EDM (electrical discharge machining), grinding, and Swiss-type machining, each used for different part geometries and tolerance requirements.

What tolerances can precision machining achieve?

Standard tolerances are typically ±0.01 mm, while high-precision machining can achieve tolerances as tight as ±0.002–0.005 mm depending on part design, material, and machining process.

How do you choose the right material for precision machining?

Material selection depends on strength, weight, corrosion resistance, heat resistance, electrical properties, cost, and the functional requirements of the final application.

How do you ensure quality control in precision machining?

Quality control includes first article inspection, in-process checks, final inspection, and CMM measurement to ensure all parts meet design specifications and tolerance requirements.