Medical CNC machining is a core manufacturing process for precision components used in implants, surgical instruments, diagnostic equipment, and microfluidic systems. This guide explains how medical CNC machining works, how to design parts for the process, which materials are suitable, how quality is controlled, and how costs are typically structured.

Overview of Medical CNC Machining

Medical CNC machining uses computer-controlled cutting tools to remove material from solid stock (metal or plastic) and produce highly accurate parts. It is used extensively for:

- Permanent and temporary implants (orthopedic, spinal, dental)

- Reusable surgical instruments and endoscopic tools

- Components for imaging systems and diagnostic devices

- Housings and precision parts for life-support and monitoring equipment

Unlike general industrial CNC machining, medical applications emphasize tight tolerances, controlled surface finishes, biocompatible materials, and strict process validation under regulatory frameworks such as ISO 13485 and FDA requirements.

Common CNC Processes Used in Medical Manufacturing

Multiple CNC processes are often combined to achieve the required geometry, accuracy, and finish on medical components.

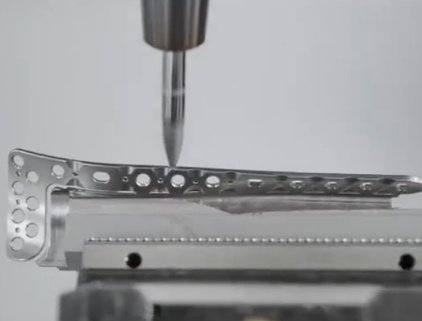

CNC Milling

CNC milling uses rotating cutting tools and typically 3–5 axes of motion to create complex 3D geometries. It is widely used for:

- Orthopedic plates, joint implant bodies, bone screws and anchors

- Instrument handles, clamps, housings, and tool bodies

- Custom surgical guides and patient-specific devices

Typical capabilities for medical CNC milling:

Tolerance range: ±0.005–0.02 mm (±0.0002–0.0008 in) for precision features

Surface roughness after milling: Ra ≈ 0.8–3.2 μm (can be improved via polishing)

Usual workpiece size: from a few millimeters up to several hundred millimeters

CNC Turning and Swiss-Type Turning

CNC turning is used for rotationally symmetric parts such as shafts, pins, connectors, and threaded components. Swiss-type (sliding headstock) turning is essential for very small, long, or slender medical parts.

Typical medical applications:

- Bone screws, dental screws, and fixation pins

- Catheter components and small connectors

- Valve components and guidewire parts

Typical capabilities:

Tolerance range: ±0.002–0.01 mm (±0.00008–0.0004 in) on critical diameters

Diameters: down to ~0.3–0.5 mm for Swiss turning, up to 25–32 mm or more for standard turning

Achievable surface roughness after turning: Ra ≈ 0.4–1.6 μm

Micro Machining

Micro machining uses specialized tools, high-speed spindles, and precise motion control to produce very small features and components. In medical applications it is used for:

Microfluidic channels and manifolds

Fine features on endoscopic and minimally invasive instruments

Tiny components for implantable devices (e.g., stimulation or monitoring implants)

Feature sizes can reach tens of micrometers, but the practical limits depend strongly on material, tooling, and machine capabilities.

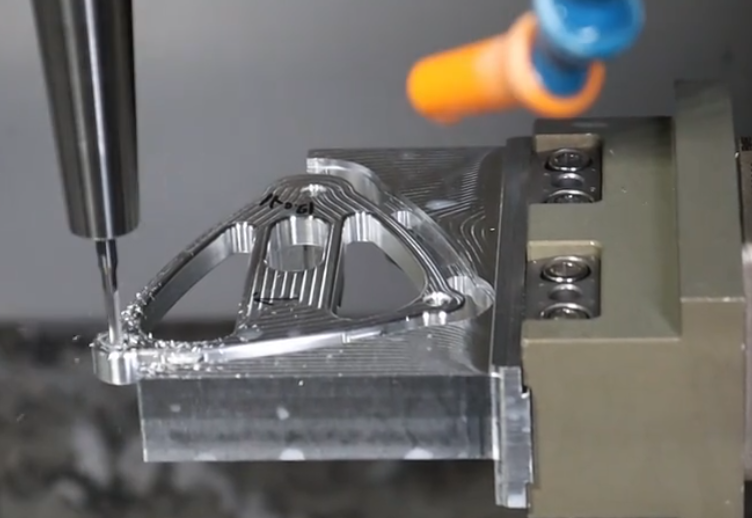

5-Axis CNC Machining

5-axis machining enables the cutting tool to approach the workpiece from multiple angles, reducing setups and allowing more complex geometries.

Typical medical uses include:

Complex orthopedic implants (hip stems, knee components)

Spinal cages with intricate lattice structures (when milled instead of additively manufactured)

Impeller-like components and complex housings for pumps and diagnostic systems

5-axis machining helps maintain accuracy across multiple faces in a single setup and improves alignment between critical features.

Design Guidelines for Medical CNC Parts

Well-considered design for manufacturability (DFM) is essential to achieve consistent quality and efficient production. In medical CNC machining, DFM must be aligned with clinical function, sterilization, and cleaning requirements.

Geometry and Feature Design

Key considerations for geometry:

Avoid unnecessary complexity: Complex 3D forms increase machining time and cost; simplify transitions and surfaces where possible while preserving clinical function.

Use consistent wall thicknesses: For metal parts, wall thickness generally ≥ 0.5–0.8 mm is preferred; very thin walls require careful fixturing and increase cycle time.

Round internal corners: Minimum internal corner radius should usually match or exceed the cutter radius (e.g., ≥ 0.5–1.0 mm) to avoid tool breakage and allow higher feed rates.

Design for tool access: Deep cavities, undercuts, and narrow slots may require special tools or multiple setups; consider whether features can be split into multiple components or redesigned for easier access.

Tolerancing for Medical Components

Tolerances should reflect clinical and assembly needs but also consider machining capabilities and cost. Overly tight tolerances raise inspection effort and machining time without always improving performance.

Typical approach:

- Use general tolerances (e.g., ±0.05–0.1 mm) for non-critical dimensions

- Apply tight tolerances (e.g., ±0.005–0.02 mm) only to functional interfaces

- Define geometric tolerances (position, concentricity, flatness) for assembly-critical features and mating surfaces

Thread tolerances for implants and bone screws often follow specific standards (e.g., ISO or ASTM-defined thread forms). In such cases, coordinate tolerances with the applicable standard and the torque or pull-out requirements.

Surface Finish and Edge Conditions

Surface finish directly influences biocompatibility, cleanability, and wear. Examples:

Surgical instruments: Often need smooth surfaces (e.g., Ra ≤ 0.8 μm) for easy cleaning and resistance to corrosion after repeated sterilization.

Bone-contacting implant surfaces: May require controlled roughness or texturing to encourage osseointegration, while articulating surfaces (e.g., joint implants) require much smoother finishes (often Ra ≤ 0.1–0.2 μm after polishing).

Microfluidic components: Smooth internal surfaces minimize dead volume, prevent particle accumulation, and help control flow.

Edge design is also important:

Sharp cutting edges on instruments must be precisely ground and controlled.

Non-functional edges should be deburred and slightly chamfered or rounded to avoid tissue damage and improve handling.

Consistent edge breaks (e.g., 0.1–0.3 mm) help cleaning and reduce risk of particulate generation.

Materials for Medical CNC Machining

Material selection affects biocompatibility, mechanical performance, manufacturability, and cost. Medical CNC machining relies heavily on metallic implant-grade alloys and engineering plastics.

| Material | Key Properties | Typical Medical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium alloys (e.g., Ti-6Al-4V ELI) | High strength-to-weight, excellent biocompatibility, good corrosion resistance | Orthopedic implants, spinal implants, dental implants, trauma fixation devices |

| Stainless steels (e.g., 316L, 17-4PH) | Good corrosion resistance, high strength; widely used for instruments | Surgical instruments, device housings, fasteners, components in sterilizable assemblies |

| Cobalt-chromium alloys | Very high wear resistance, high strength, good corrosion resistance | Joint replacement components, wear-resistant implant surfaces |

| Medical-grade aluminum alloys | Lightweight, good machinability; anodizable for protection | Equipment housings, fixtures, instrument handles, non-implant components |

| PEEK and medical-grade PEEK composites | High-temperature resistance, radiolucent, good fatigue resistance, biocompatible | Spinal cages, implant components, structural parts in imaging areas |

| Acetal (POM), medical-grade | Low friction, good dimensional stability, good machinability | Gears, valves, connectors, disposable or semi-disposable components |

| Ultem (PEI) and PPSU | High-temperature stability, good chemical resistance, sterilizable | Reusable instrument components, sterilizable trays and housings |

| PTFE and fluoropolymers | Very low friction, chemical inertness | Seals, gaskets, components in fluid handling systems |

Titanium and Titanium Alloys

Titanium alloys, especially Ti-6Al-4V ELI (extra low interstitial), are widely used for load-bearing implants. They offer:

High specific strength and good fatigue resistance

Excellent corrosion resistance in physiological environments

Biocompatibility and favorable bone interaction

Machining considerations:

Titanium has low thermal conductivity, so heat concentrates at the cutting edge; use sharp tools, appropriate cutting speeds, and abundant coolant.

Chip control is important to maintain surface finish and avoid built-up edge.

Tool wear must be monitored closely, especially for small features and micro machining.

Stainless Steels for Medical Use

316L and 17-4PH stainless steels are standard choices for surgical instruments and various device components.

316L: Austenitic stainless steel with low carbon content; offers high corrosion resistance, especially important in repeated sterilization cycles and contact with body fluids.

17-4PH: Precipitation-hardened stainless steel with higher strength; used when mechanical loads are higher.

Machining considerations:

Austenitic grades can be prone to work hardening; maintain adequate feed per tooth and avoid dwelling in cut.

High-quality coolants and polished tools help achieve good surface finish and reduce burrs.

Heat treatment (for 17-4PH) must be controlled and documented when used for regulated devices.

Plastics and Polymers

Medical-grade plastics extend CNC machining to applications requiring electrical insulation, transparency, radiolucency, or weight reduction.

PEEK: Often used in spinal and orthopedic applications; requires sharp tools and controlled cutting conditions to avoid surface defects. Radiolucent, enabling easier imaging of surrounding bone.

Acetal (POM): Used for precision mechanisms and components with low friction; dimensional stability is generally good.

Ultem (PEI) and PPSU: Used for high-temperature components that must endure repeated autoclave cycles.

Proper material certification (e.g., documentation of compliance with USP Class VI or ISO 10993 testing, where applicable) is critical when materials are used in contact with the body or blood.

Dimensional Accuracy and Tolerances

Medical CNC components often require higher accuracy than general industrial parts. Dimensional control is crucial for assemblies, moving joints, and clinically critical interfaces.

Typical tolerance bands:

General machining features: ±0.05–0.1 mm

Precision fits and alignment surfaces: ±0.01–0.02 mm

Critical implant interfaces, mating with standard instruments: ±0.005–0.01 mm

Micro features (e.g., microfluidic channels): tolerances may be in the range of ±0.01–0.05 mm, depending on feature size

Achieving these tolerances depends on machine capability, fixture design, temperature control, and inspection method. For fine tolerances, coordinate measuring machines (CMMs), optical measurement, and high-resolution probes are used.

Surface Finishing and Texturing

After CNC machining, additional finishing operations are often required to meet functional and regulatory requirements.

Mechanical Finishing

Common techniques:

Deburring: Manual or automated deburring removes sharp edges and residual burrs from small holes and slots.

Polishing: Improves surface roughness and appearance; necessary for articulating surfaces and high-end instruments.

Abrasive blasting: Used to produce matte finishes or controlled roughness on implant surfaces. Parameters such as media type, pressure, and exposure time must be controlled and documented.

Electrochemical and Chemical Finishing

Stainless steel instruments often undergo passivation (controlled oxidation) to enhance corrosion resistance. Parameters like acid type, temperature, and exposure time must be controlled.

For certain implant alloys, electro-polishing can be used to reduce surface roughness and remove micro-burrs from internal features. The process can improve fatigue performance by reducing surface defects.

Coatings and Surface Modifications

Some medical components require coatings or surface modifications applied after machining. Examples include:

Hard coatings on cutting instruments to improve wear resistance

Bioactive coatings on implants to enhance bone bonding

Lubricious coatings on sliding surfaces

In CNC machining, the design must account for the thickness and dimensional impact of such coatings, especially when tolerances are tight.

Quality Control and Regulatory Considerations

Quality control in medical CNC machining is closely linked with regulatory standards. The manufacturing process must be capable, stable, and well documented.

Quality Management Systems

Medical CNC providers often operate under recognized standards such as ISO 13485 (medical device quality management systems) and, where applicable, FDA Quality System Regulation (QSR) requirements.

Key elements:

Documented procedures for machining, inspection, calibration, and maintenance

Traceability of materials, tools, process parameters, and inspection results

Qualification and validation of critical processes

Inspection and Measurement

Measurement strategies depend on part complexity and risk classification. Typical methods include:

CMM measurement for complex 3D geometries and tight tolerances

Optical and vision systems for small features and micro components

Surface roughness measurement using profilometers or optical systems

Hardness, tensile, or fatigue testing when required by product specifications or standards

Sampling plans (e.g., based on statistical acceptance sampling) are used in production to confirm that machining processes remain within control limits.

Cost Structure of Medical CNC Machining

Costs for medical CNC machining result from several interacting factors: design complexity, material, production volumes, quality requirements, and secondary operations. Understanding the cost structure helps in making design and sourcing decisions.

| Cost Element | Description | Impact on Total Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Raw material price, bar/plate yield, certification requirements | Significant for titanium, cobalt-chrome, and certified medical-grade plastics |

| Machining time | Cycle time per part on milling/turning centers | One of the largest cost components; strongly influenced by design |

| Setup and programming | CAM programming, fixture design, machine setup | High impact for low-volume or prototype work; spreads out over large batches |

| Tooling and consumables | Cutting tools, fixtures, gauges, coolants | More significant for hard-to-machine materials and micro features |

| Finishing and cleaning | Deburring, polishing, passivation, ultrasonic cleaning | Can be substantial for instruments requiring high cosmetic quality |

| Inspection and documentation | Dimensional inspection, validation, reports, traceability documentation | Higher than in general machining due to regulatory requirements |

| Regulatory and quality overhead | Maintaining QMS, audits, record keeping | Embedded in hourly rates for medical-focused suppliers |

Material and Stock Utilization

Material cost is influenced by:

Base material price: Medical-grade titanium, cobalt-chrome, and certified polymers are more expensive than general industrial grades.

Stock dimensions: Oversized bar or plate increases wasted material.

Yield: Parts with complex contours may require larger starting blocks; design adjustments can sometimes improve yield.

In many medical applications, full material traceability and specific certifications are mandatory, adding to procurement and documentation costs.

Effect of Design on Machining Time

Feature complexity, tight tolerances, and deep cavities increase machining time. Common influences:

Small tools for fine features require lower feed rates and more passes.

Multi-sided parts requiring several setups add non-cutting time.

Extensive deburring and polishing needs increase manual labor.

Design optimizations, such as using standardized hole sizes, avoiding extremely deep narrow pockets, and minimizing non-critical surface curvature, can reduce machining time while maintaining function.

Batch Size and Production Volume

Setup and programming costs are fixed for a given part; they are distributed across the number of pieces produced:

Prototypes and small batches: Higher unit cost due to significant setup share per piece and more intensive development-level inspection.

Medium to large production runs: Lower unit cost as setup and programming are amortized; process optimization and dedicated fixturing become viable.

In medical device development, it is common to have several iterations of low-volume prototypes before toolpaths and fixtures are finalized for series production.

Cleaning, Packaging, and Sterilization Considerations

Although cleaning and sterilization may not occur at the machining supplier, part design and machining choices influence how easily components can be cleaned and sterilized later.

Design and machining considerations:

Avoid blind holes and deep narrow slots where contaminants can accumulate and are difficult to remove.

Ensure internal corners and undercuts that contact biological material are accessible for cleaning or are minimized where clinically acceptable.

Surface roughness affects debris retention; smoother surfaces are often easier to clean but may not be suitable for every application (e.g., bone ingrowth surfaces).

Packaging for machined medical components often includes protective trays or inserts to prevent damage of critical surfaces during transport and handling. For sterile-packaged devices, validated packaging processes and materials are required, but those usually occur at the device manufacturer or specialized packaging facility.

Supplier Selection and Collaboration

Effective collaboration between device designers and machining partners is essential for robust, cost-effective medical components.

Key aspects when evaluating CNC suppliers for medical work:

Relevant certifications, such as ISO 13485, and experience with similar device classes.

Documented process controls and traceability systems.

Capability range: number of axes, micro machining, 5-axis, Swiss turning, and in-house finishing or inspection capabilities.

Experience with specific materials (e.g., titanium implants vs. plastic disposable components).

Ability to provide design for manufacturability feedback during development.

Clear technical communication, including detailed drawings, models, material specifications, and inspection requirements, reduces the risk of misinterpretation and nonconforming parts.

Typical Issues in Medical CNC Machining

Some recurring issues arise when transitioning from design to production in medical CNC machining:

Overly tight tolerances applied uniformly across drawings, leading to unnecessary cost and production difficulty.

Complex geometries with limited tool access that require multiple setups, special tools, or compromise on surface finish.

Insufficient information about cleaning, sterilization, and surface requirements during early design stages, causing rework when guidelines or regulatory expectations are clarified later.

Underestimation of validation and documentation time required to support regulatory submissions.

Addressing these pain points early by involving manufacturing engineers and quality experts in the design phase leads to more robust and economical products.

Trusted Medical CNC Machining Partner – XCM

At XCM, our medical CNC machining services operate under a quality management system compliant with ISO 13485:2016, ensuring consistent quality, traceability, and regulatory compliance. We specialize in high-precision CNC machining for medical devices, surgical instruments, and critical components, using medical-grade materials and advanced manufacturing technology. With strict process control, tight tolerances, and reliable lead times, XCM supports safe, accurate, and scalable medical manufacturing for global healthcare applications.

FAQ

What is medical CNC machining?

Medical CNC machining is a precision manufacturing process that uses computer-controlled machines to produce medical devices, surgical instruments, and implant components with high accuracy and consistency.

How does CNC machining support custom medical device designs?

CNC machining allows for precise customization and design flexibility, making it suitable for patient-specific and specialized medical components.

What are the benefits of CNC machining over other manufacturing methods for medical parts?

CNC machining offers superior accuracy, excellent surface finish, strong material properties, and consistent quality compared to many alternative manufacturing methods.

Can CNC machining produce medical implants?

Yes, CNC machining is widely used to manufacture medical implants such as orthopedic, dental, and spinal components that require high precision and biocompatibility.