CNC turning is one of the most widely used machining processes for cylindrical parts, shafts, bushings, and precision components across automotive, aerospace, medical, energy, and general industrial applications. While CNC lathes can achieve tight tolerances and excellent surface finishes, many projects suffer from unnecessarily high costs that are not directly tied to functional quality.

This guide explains, in a systematic and technical way, how to reduce CNC turning costs while maintaining or even improving part quality. It covers design, material, process planning, tooling, programming, setup strategies, inspection, and supplier collaboration so that engineers, buyers, and manufacturing planners can make informed decisions.

Where CNC Turning Costs Come From

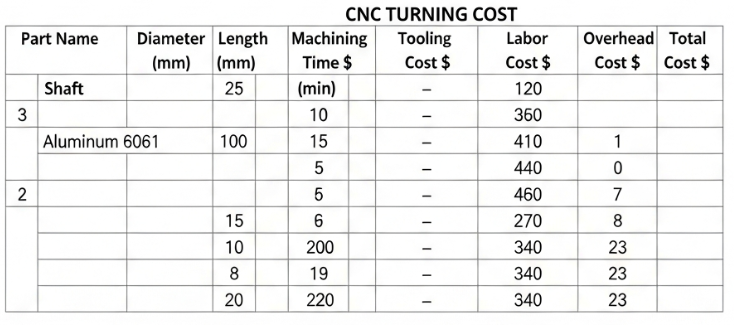

To reduce cost effectively, it is essential to understand the primary cost drivers in CNC turning. Broadly, total cost per part is influenced by:

- Material costs

- Machine time and overhead

- Tooling and consumables

- Setup and changeover

- Programming and engineering

- Inspection and quality assurance

Optimizing only one element in isolation often shifts costs elsewhere. A balanced approach targets the highest cost contributors without undermining geometric accuracy, surface integrity, or long-term reliability.

Material Costs and Utilization

Material cost is not only the price per kilogram of bar stock or blanks; it also includes yield and chips. For turned parts, material utilization is strongly affected by:

- Starting bar diameter and length

- Cut-off width and facing allowances

- Overlength and chucking allowances

Selecting the smallest feasible bar size and minimizing non-functional stock can significantly reduce material waste, especially in high-volume production.

Machine Time and Cycle Time

Machine time is typically the dominant cost factor. It includes:

- Cutting time: the period when the tool is engaged with the part

- Non-cutting time: tool changes, rapid moves, indexing, spindle acceleration/deceleration, part loading/unloading

Even small reductions in cycle time, multiplied across thousands of parts, can yield substantial savings without changing quality targets.

Tooling, Setup, and Overhead

Tooling costs comprise cutting inserts, tool holders, boring bars, drills, and wear items such as center drills and cut-off tools. Setup encompasses:

- Chuck jaw preparation and installation

- Tool offset setting and verification

- Program loading and dry runs

- First article inspection and adjustments

For low- and medium-volume jobs, setup time often dominates cost per part. For high-volume work, tooling and cycle time are more critical.

Design for Manufacturability in CNC Turning

Part design is usually the single biggest lever in CNC turning cost reduction. Many expensive features add little functional value. Design for Manufacturability (DFM) adapts geometry and tolerances to the capabilities of CNC lathes without compromising performance.

Choose Turning-Friendly Geometries

CNC turning is inherently efficient for rotationally symmetric features. Cost rises when the design departs from this strength. Consider these design guidelines:

- Prefer simple cylindrical and conical surfaces over complex contours

- Eliminate unnecessary sharp internal corners that require special tools or secondary processes

- Use constant diameters where possible rather than frequent step changes

- Limit deep, narrow grooves that need slender, vibration-prone tools

- Avoid extremely slender parts with high length-to-diameter ratios that demand steady rests or follow rests

Where non-rotational features are needed, evaluate whether they can be produced by live tooling on a turning center or if they justify a secondary milling operation.

Optimize Tolerances and Fits

Unnecessarily tight tolerances are a major cost driver. They can reduce cutting speeds, increase scrap rates, require more inspection, and necessitate more stable fixtures and tools. When defining tolerances:

- Align tolerances with functional requirements rather than copying legacy drawings

- Use standard tolerance grades (e.g., ISO tolerance classes) appropriate to the part’s function

- Relax tolerances where they are non-critical, especially on non-mating surfaces

- Apply geometric tolerances (e.g., runout, concentricity) only where needed to ensure assembly or performance

In many applications, dimensional tolerances in the range of ±0.05 mm to ±0.1 mm can be held easily and economically. Tolerances tighter than ±0.01 mm often require optimized process control, slower finishing passes, and more frequent tool changes, increasing cost.

Specify Practical Surface Finish Requirements

Surface roughness affects friction, sealing, fatigue resistance, and aesthetics. However, each reduction in Ra (arithmetic average roughness) usually increases cycle time and tool wear. Consider:

- Use different surface finish specifications for functional and non-functional surfaces

- For many general mechanical parts, Ra 1.6–3.2 μm is sufficient

- Reserve Ra ≤ 0.8 μm for sealing surfaces, bearing seats, or sliding interfaces that truly need it

An extra finishing pass with reduced feed and speed can easily add several seconds per part. Across high volumes, this has a measurable cost impact.

Rationalize Chamfers, Radii, and Edge Conditions

Edge features are often over-specified. To reduce cost:

- Use standard chamfer sizes (e.g., 0.5 × 45°, 1 × 45°) that can be produced with standard tools

- Where possible, specify “break edges” rather than specific chamfer dimensions for non-critical edges

- Avoid very small radii that require special form tools or additional passes

Standardized and simple edge callouts reduce programming complexity, tool count, and inspection time.

Material Selection and Its Impact on Cost and Quality

Material choice affects raw material cost, machinability, tool life, achievable surface finish, and dimensional stability. Selecting a material optimized for both performance and machining can reduce overall cost significantly.

Evaluate Machinability Ratings

Steels and alloys often have published machinability ratings relative to a benchmark material. Better machinability generally allows:

- Higher cutting speeds and feeds

- Longer tool life

- Less power consumption

- Improved surface finish at given cutting parameters

Where design requirements allow, choosing a more machinable grade (e.g., free-cutting or leaded steels, sulfurized steels, or aluminum alloys) can reduce machining time and tooling costs while maintaining mechanical properties within acceptable ranges.

Balance Material Properties and Machinability

While strength, hardness, corrosion resistance, and temperature performance must be respected, it is often possible to:

- Select a nearby grade within the same standard that offers improved machinability

- Use heat treatment after rough machining to improve machinability during the bulk of material removal

- Separate critical and non-critical components so only truly demanding parts use the most difficult-to-machine alloys

For example, using a normalized condition for pre-machining high-strength parts, followed by final heat treatment and finishing operations, can provide a compromise between machinability and final performance.

Optimize Stock Size and Form

Material form significantly affects cost in turning:

- Drawn or ground bar stock is more expensive but may improve straightness and surface finish, reducing machining allowances

- Hot-rolled bar is cheaper but may require more stock removal to achieve accurate diameters and surface finishes

Selecting a bar size just slightly larger than the maximum final diameter reduces chip volume. For instance, using 20 mm bar for a 19 mm maximum diameter part is typically more economical than using 25 mm bar, especially at scale.

Reducing Cycle Time Without Compromising Quality

Cycle time reduction is one of the most direct ways to lower CNC turning costs. The challenge is to optimize cutting conditions and operations so that part quality remains within specifications or improves.

Optimize Cutting Parameters

Cutting speed (Vc), feed rate (f), and depth of cut (ap) strongly influence both productivity and surface integrity. Practical approaches include:

- Roughing at higher depth of cut and feed to remove material quickly

- Finishing at lower feed with moderate depth to achieve desired surface finish and tolerances

- Using tool manufacturer recommendations as a starting point and adjusting based on tool wear patterns and measured part quality

For example, in steel turning with carbide inserts, it is common to use roughing feeds in the range of 0.2–0.4 mm/rev and finishing feeds of 0.05–0.15 mm/rev, adjusting with regard to material and required Ra.

Minimize Non-Cutting Time

Non-cutting time, while not directly producing chips, contributes to total cycle time. Strategies to reduce it include:

- Optimizing tool path to reduce unnecessary retracts and rapid movements

- Combining operations in a single tool where possible (e.g., turning and facing with one insert)

- Using automatic tool changers efficiently and minimizing the number of tools per part

- Implementing automatic part loading and unloading devices for higher volumes

Even reductions of 0.5–1.0 seconds per tool change or per part handling operation can be meaningful in serial production.

Combine Operations with Multi-Tasking Machines

Modern turning centers often provide capabilities such as:

- Live tooling for drilling and milling

- Y-axis for off-center features

- Sub-spindles for back-working and part transfer

Combining turning, facing, drilling, tapping, and light milling in one setup reduces total handling and fixture costs, and often improves concentricity and positional accuracy. This can eliminate secondary operations and associated machine time, labor, and setup.

Tooling Strategy for Cost-Effective CNC Turning

Tooling decisions strongly influence both cost and quality. A balanced tooling strategy considers insert type, grade, nose radius, and tool holding to achieve stable, predictable performance.

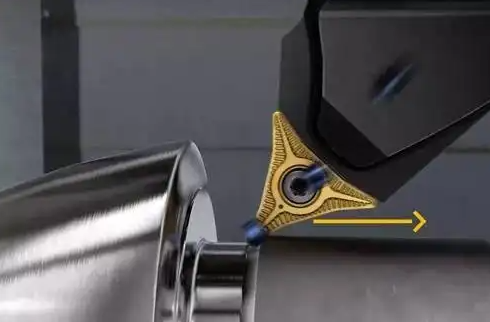

Select Appropriate Insert Geometry and Grade

Insert geometry affects chip control, cutting forces, and surface finish. Key considerations include:

- Positive versus negative rake inserts: positive for lower cutting forces and better chip evacuation; negative for stronger edges

- Appropriate chip breaker design to avoid chip wrapping and surface scratching

- Wear-resistant grades for abrasive materials, tougher grades for interrupted cuts

Using a general-purpose insert for both roughing and finishing may be acceptable for some parts, but dedicated roughing and finishing inserts often yield better tool life and surface finish at lower overall cost per part.

Optimize Nose Radius and Surface Finish

Nose radius affects both surface finish and cutting forces:

- Larger radius (e.g., 0.8–1.2 mm) allows higher feed rates and stronger cutting edge but may induce chatter on slender parts

- Smaller radius (e.g., 0.2–0.4 mm) can produce fine detail and reduce cutting forces but is more fragile

Matching nose radius to required surface finish and part stiffness can reduce the number of passes and improve tool life.

Tool Life Management

Changing inserts too early wastes tool potential; changing too late risks scrap and rework. A controlled tool life strategy might include:

- Setting tool life based on a defined number of parts or cutting time at which wear is predictable

- Monitoring wear patterns to adjust cutting parameters or grades

- Standardizing tool life data for similar materials to streamline planning

Predictable tool life helps maintain consistent surface finish and dimensions, reducing variability and inspection failures.

Part Setup, Fixturing, and Workholding

Effective workholding ensures stability, concentricity, and accurate repeatability. Optimized setups reduce scrap, vibration, and time spent aligning parts.

Choose Efficient Workholding Methods

Common CNC turning workholding options include:

- Three-jaw or four-jaw chucks

- Collet chucks for smaller diameter parts

- Mandrels and expanding collets for internal gripping

- Soft jaws machined to part profile

Collets offer improved concentricity and faster clamping for high-volume small parts. Soft jaws allow robust clamping of complex features and can reduce scrap due to slippage or distortion.

Minimize Number of Setups

Each additional setup introduces potential misalignment and adds labor and machine time. Design and process planning should seek to:

- Finish as many features as possible in a single chucking

- Use sub-spindle or part transfer to machine the second side without manual re-clamping

- Employ soft jaws that allow access to all required features with minimal reclamping

Reducing from two setups to one can dramatically improve geometric relationships (such as concentricity between diameters) while cutting labor and inspection complexity.

Control Part Distortion

Thin-walled or long slender parts are prone to deflection and distortion, which can cause taper, roundness errors, and chatter. Cost-effective methods to manage these issues include:

- Using tailstock, steady rests, or follow rests where appropriate

- Sequencing machining to maintain rigidity as long as possible (e.g., roughing external features before internal boring)

- Optimizing clamping force to avoid deformation of thin sections

Stable, repeatable dimensional control reduces the need for corrective passes and rework.

Programming Practices That Influence Cost

NC program structure and strategies have a direct impact on cycle time, tool life, surface finish, and reliability. Efficient programming can deliver meaningful cost reductions at no capital investment.

Use Efficient Tool Paths

Well-designed tool paths reduce unnecessary motions and maintain cutting stability. Good practices include:

- Using constant surface speed (CSS) modes where beneficial to maintain consistent cutting conditions across diameter changes

- Avoiding sudden changes in direction that promote chatter or tool marks

- Sequencing roughing and finishing passes to minimize rapid moves and idle time

Optimized tool paths also reduce peak cutting forces, improving dimensional consistency and surface quality.

Standardize Programming Structures

Standardization across similar parts makes it easier to implement improvements and reduces programming effort:

- Use common subroutines for repetitive features like grooves, threads, and chamfers

- Standardize naming conventions for tools, offsets, and operations

- Reuse proven cycles (e.g., canned cycles) where possible to reduce debugging time

Standardized programming also reduces the risk of errors when different programmers work on related parts.

Leverage Simulation and Verification

Offline simulation and verification can catch collisions, over-travel, and unexpected tool behaviors before they cause scrap or damage:

- Simulate tool paths with accurate machine models where available

- Verify clearance between tool, chuck, and tailstock for all operations

- Check that retracts and approaches are safe yet efficient

Reducing the need for manual trial runs and corrections saves machine time and improves shop throughput.

Inspection, Quality Assurance, and Cost Control

Quality control activities can represent a significant portion of total cost, especially for tight-tolerance parts. The objective is to ensure specification compliance with minimal waste of time and resources.

Align Inspection to Critical Features

Not all dimensions have equal importance. To control cost:

- Prioritize 100% inspection for critical features that directly affect safety, function, or assembly

- Use reduced sampling plans for non-critical dimensions when permitted by quality requirements

- Group related measurements to be taken in one setup on the measuring equipment

Reducing unnecessary checks allows inspectors and machinists to focus on controlling what truly matters.

Use Appropriate Measuring Equipment

Overly precise or complex instruments for simple dimensions increase inspection time. Consider:

- Using calipers and go/no-go gauges for straightforward dimensions where tolerances allow

- Employing micrometers, bore gauges, and dial indicators for tighter features

- Reserving coordinate measuring machines (CMM) for complex geometries or relationships that cannot be measured easily with simpler tools

Matching measurement method to tolerance and geometry reduces cost without compromising quality assurance.

Implement In-Process Control

Detecting deviations during machining is far more economical than finding them at final inspection. Practical measures include:

- Setting in-process check intervals based on tool life and process stability

- Using statistical process control (SPC) charts for critical dimensions

- Training operators to recognize tool wear indicators and adjust offsets proactively

Stable processes reduce scrap, rework, and inspection overturns, directly lowering total manufacturing cost.

Batch Size, Setup Optimization, and Economies of Scale

Batch size has a strong impact on unit cost. Setup time and programming costs are distributed over the number of parts produced. Understanding this relationship informs sourcing and scheduling decisions.

Amortizing Setup Over Batch Size

Long and complex setups are justifiable for large batches but not for very small ones. To make informed decisions:

- Estimate setup time, including programming, tooling, and first article approval

- Divide setup time cost across batch size to understand its contribution per part

- Where feasible, group similar parts in a family to share setups and tooling

For small batches, consider simplifying workholding or tolerances to reduce setup, even if it slightly increases cycle time, as the net effect may lower cost per part.

Family-of-Parts Approach

Grouping parts with similar diameters, lengths, and features can yield substantial advantages:

- Shared soft jaws or collets

- Common tooling lists and NC program templates

- Reduced need for unique fixtures and setup steps

By designing new parts to align with existing families where possible, companies can reuse established processes and lower NPI (new product introduction) costs.

Supplier Collaboration and Communication

CNC turning costs are not determined solely in-house. When parts are outsourced, active collaboration with machining suppliers can uncover economically viable alternatives while maintaining or improving quality.

Early Supplier Involvement

Involving machinists and process engineers early in the design phase can lead to more manufacturable parts. Benefits include:

- Feedback on feasible tolerances and surface finishes

- Recommendations on material grades and stock sizes

- Identification of features that will drive up cost disproportionately

Early adjustments to drawings are generally much cheaper than late-stage changes or ongoing cost penalties.

Clear Technical Documentation

Ambiguities in technical drawings and specifications can cause conservative assumptions and higher quotes. To avoid this:

- Ensure drawings clearly define all dimensions, tolerances, and surface finish requirements

- Avoid conflicting notes or redundant dimensions

- Provide 3D models when geometry is complex

Clear documentation reduces questions, rework, and quoting uncertainty, often resulting in lower pricing.

Long-Term Partnerships

Building stable relationships with capable CNC turning suppliers encourages investment in optimal tooling, fixtures, and process improvements. Over time, suppliers can:

- Develop dedicated tooling and programs optimized for recurring parts

- Share data on process capability and suggest tolerance relaxations where justified

- Offer better pricing based on predictable demand and efficient scheduling

Reliable supply chains with aligned technical understanding support consistent quality at competitive cost.

Cost and Quality Considerations by Application Type

Different industries and applications prioritize quality attributes differently. Understanding these priorities helps tailor cost reduction strategies.

| Application Type | Typical Key Requirements | Primary Cost Levers |

|---|---|---|

| General industrial components | Moderate tolerances, robust function, reasonable surface finish | Material selection, cycle time, simplified inspection |

| Automotive precision parts | High repeatability, controlled fits, large volumes | Cycle time optimization, multi-tasking, automated handling |

| Aerospace components | Tight tolerances, documentation, traceability | Process stability, in-process control, inspection efficiency |

| Medical implants/instruments | Biocompatible materials, surface integrity, cleanliness | Material choice, finishing processes, controlled handling |

| Hydraulic/pneumatic components | Sealing surfaces, concentricity, surface finish | Surface finish optimization, appropriate tool selection |

Recognizing which quality attributes are critical in each application allows cost efforts to focus where they will not compromise functional performance or regulatory compliance.

Typical Pain Points and How to Address Them

Many organizations experience recurring issues that inflate CNC turning costs. Addressing these systematically can yield lasting savings.

| Pain Point | Impact on Cost | Mitigation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Too many tight tolerances on non-critical features | Longer cycle time, higher scrap, more inspection | Review drawings and relax non-functional tolerances |

| Frequent setup changes for similar parts | High setup cost per part, lower machine utilization | Implement family-of-parts fixtures and standardized tooling |

| Chatter and vibration issues | Poor surface finish, rework, conservative feeds | Optimize tool holding, nose radius, cutting parameters, and support |

| Unpredictable tool life | Unexpected scrap and downtime, conservative parameters | Establish monitored tool life, adjust grades and conditions |

| Overly complex inspection routines | Extended lead times, higher labor cost | Focus inspection on critical features, use appropriate gauges |

By mapping observed problems to targeted actions, companies can reduce cost in a controlled manner while preserving or enhancing quality outcomes.

Integrating Cost Reduction into the CNC Turning Lifecycle

Effective cost control is not a one-time activity. It should be integrated into the entire lifecycle of CNC-turned components:

- Design and development: incorporate DFM principles, select machinable materials, and engage suppliers early

- Process planning: choose efficient setups, tooling, and NC strategies aligned with batch size

- Production: monitor cycle time, tool life, and quality metrics, adjusting parameters as needed

- Continuous improvement: collect data on scrap, rework, and downtime to refine processes and design standards

This systematic approach ensures that cost reduction measures are sustainable, repeatable, and compatible with quality objectives and customer requirements.

FAQ: CNC Turning Cost Reduction

How much can I reduce CNC turning costs by optimizing design?

The potential cost reduction depends on the starting point and complexity of the part. In many cases, revising tolerances, simplifying geometries, and adjusting surface finish requirements can reduce machining and inspection effort enough to cut part cost by a noticeable margin. Parts with many unnecessary tight tolerances, complex contours, or multiple setups typically offer the largest savings. The key is to ensure that any changes are carefully evaluated against functional and regulatory requirements so quality is not compromised.

Does using cheaper material always reduce CNC turning cost?

Using a lower-cost material per kilogram does not necessarily reduce overall part cost. Materials with poor machinability can significantly increase cycle time, tool wear, and scrap rates, offsetting any savings in raw material price. A more machinable material that meets performance requirements can often reduce total cost even if its raw price is higher. Evaluating machinability, tool life, and process stability alongside raw material cost provides a more accurate picture of the true cost per part.