CNC turning and CNC grinding are two core processes for producing high-accuracy rotational components such as shafts, pins, bushings, and bearing seats. Although they both work with cylindrical geometries, they remove material in very different ways and are suited to different stages of manufacturing. Selecting the right process directly affects dimensional accuracy, surface quality, throughput, tool life, and overall cost.

This guide explains CNC turning and CNC grinding in detail, compares their technical capabilities, and provides practical guidelines to choose the best process or combination of processes for your parts.

Fundamentals of CNC Turning

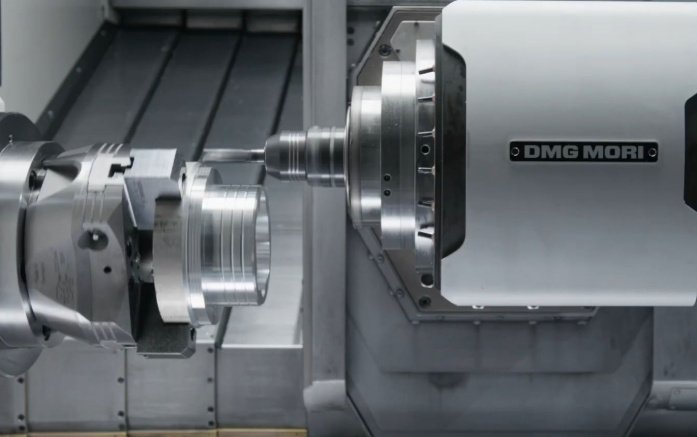

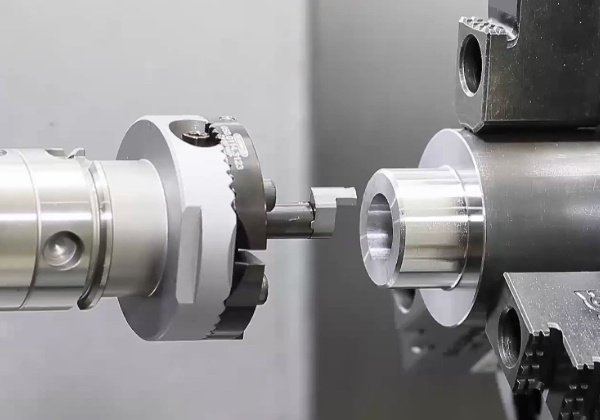

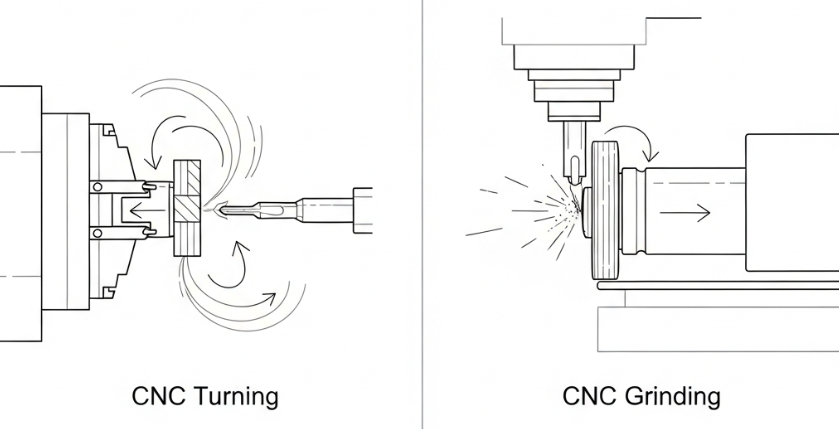

CNC turning is a subtractive machining process where a rotating workpiece is cut by a stationary or linearly moving cutting tool. It is commonly performed on CNC lathes or turning centers and is widely used to produce cylindrical, conical, and complex rotational profiles.

1. Process principle

In CNC turning:

- The workpiece is clamped in a chuck, collet, or between centers and rotated around its axis.

- A single-point cutting tool feeds along or across the rotating workpiece.

- Material is removed in the form of chips by shear deformation.

The cutting conditions are generally defined by cutting speed (m/min or sfm), feed rate (mm/rev or in/rev), and depth of cut (mm or in). CNC control allows precise positioning and contouring of the tool to generate complex geometries in a single setup.

2. Typical operations in CNC turning

Common turning operations include:

- Facing: Machining the end face of the workpiece to establish a datum surface.

- External turning: Reducing the outer diameter to specified dimensions.

- Profiling/contouring: Producing tapers, radii, and complex external shapes.

- Grooving and parting: Cutting grooves, snap-ring seats, and parting off components.

- Threading: Generating internal and external threads.

- Boring: Enlarging or finishing internal diameters.

- Drilling and reaming: Using the spindle or live tools to produce axial holes.

Advanced turning centers may also support milling, drilling at different angles, and live tooling for more complex parts, but the core principle remains material removal by a cutting tool acting on a rotating workpiece.

3. Workpiece geometries suitable for CNC turning

CNC turning is most effective for parts that are:

- Rotationally symmetric about a central axis.

- Moderate to long length relative to diameter (with appropriate support, such as tailstock or steady rests, for slender parts).

- Designed with external or internal cylindrical, conical, or complex radial features.

Typical examples include shafts, axles, pins, rollers, bushings, couplings, flanges, and threaded components.

4. Materials commonly machined with CNC turning

CNC turning can handle a broad range of materials, including:

Metals:

• Carbon steels (e.g., 1018, 1045)

• Alloy steels (e.g., 4140, 4340)

• Stainless steels (e.g., 303, 304, 316, 17-4PH)

• Aluminum alloys (e.g., 6061, 7075)

• Copper and copper alloys (brass, bronze)

• Titanium alloys

• Nickel-based alloys (Inconel, Hastelloy) with appropriate tooling

Non-metals:

• Engineering plastics (POM, PEEK, PTFE, nylon)

• Composites and graphite (with suitable tooling and dust control)

The machinability and achievable surface finish depend strongly on material hardness, microstructure, and work-hardening behavior.

5. Precision, surface finish, and capacity of CNC turning

Typical performance ranges for CNC turning under controlled conditions are:

Dimensional tolerance (standard production):

• ±0.020 mm to ±0.050 mm (±0.0008 in to ±0.0020 in)

Dimensional tolerance (precision, fine turning):

• ±0.005 mm to ±0.010 mm (±0.0002 in to ±0.0004 in), depending on machine rigidity, tool, and material

Surface roughness (Ra, after turning):

• Roughing passes: approx. 1.6–3.2 µm Ra

• Finishing passes with sharp carbide or CBN tools: approx. 0.4–1.6 µm Ra

• High-precision turning on rigid machines can sometimes achieve approx. 0.2–0.4 µm Ra

Part size capacity varies by machine, but common ranges are:

• Maximum swing (diameter over bed): approx. 200–600 mm or more

• Maximum turning length: from a few hundred millimeters up to several meters on long-bed lathes

These figures are approximate and depend on machine configuration, fixturing, and part geometry.

Fundamentals of CNC Grinding

CNC grinding is a high-precision process that removes material from a workpiece using an abrasive wheel. Instead of a cutting edge, countless hard abrasive grains on the wheel surface perform small cutting actions simultaneously. CNC grinding is primarily used for finishing operations where tight tolerances, excellent surface finishes, and precise geometrical control are required.

1. Process principle

In CNC grinding:

- The grinding wheel rotates at high speed and contacts the workpiece surface.

- Individual abrasive grains penetrate the material, shear off tiny chips, and gradually remove stock.

- The wheel is periodically dressed to restore geometry and cutting ability.

Grinding requires carefully controlled wheel speed, work speed, feed rate, depth of cut (often measured in microns), and coolant delivery. CNC controls enable precise positioning and complex grinding paths, especially for camshafts, crankshafts, and other intricate shapes.

2. Types of CNC grinding relevant to turned parts

For parts that could also be turned, the most relevant CNC grinding methods are:

• Cylindrical grinding: Workpiece rotates and is fed past a rotating grinding wheel. Used for external diameters, often after turning.

• Internal cylindrical (ID) grinding: Used to finish internal bores with high accuracy and surface quality.

• Centerless grinding: Workpiece is supported between a grinding wheel and a regulating wheel without centers, suitable for high-volume production of small cylindrical parts.

• Surface grinding (for flat faces on turned parts): Provides flat and parallel end faces, step faces, or mounting surfaces.

3. Wheel types and parameters

The choice of grinding wheel is critical for both performance and part quality. Key parameters include:

• Abrasive type: Common abrasives are aluminum oxide (Al2O3), silicon carbide (SiC), cubic boron nitride (CBN), and diamond. Aluminum oxide is widely used for steels; CBN is suitable for hardened steels; diamond is often used for carbides and ceramics.

• Grit size: Determines surface finish and material removal characteristics. Coarser grits remove material faster but produce rougher surfaces; finer grits produce smoother finishes.

• Hardness grade: Indicates the wheel’s ability to retain abrasives. Softer grades release dull grains quickly; harder grades hold grains longer.

• Structure: Describes spacing between grains and porosity, affecting coolant access and chip removal.

• Bond type: Common bonds include vitrified, resin, metal, and hybrid bonds, which influence wheel strength and performance.

Typical grinding wheel speeds range from about 20 to 60 m/s, depending on wheel type and application. Depth of cut is often in the range of a few micrometers to a few tenths of a millimeter per pass.

4. Materials and applications for CNC grinding

CNC grinding is used on materials that require high hardness or high dimensional precision, such as:

• Hardened steels (e.g., 58–64 HRC bearing steels)

• Tool steels and high-speed steels

• Carbide and ceramic components

• Nitrided, carburized, or induction-hardened surfaces

• High-temperature alloys

Typical applications include:

• Bearing journals and races

• Hydraulic and pneumatic cylinder rods

• Precision shafts and spindles

• Gears, splines, and keyways (often after prior turning and heat treatment)

• Molding and tooling components

5. Precision and surface finish in CNC grinding

CNC grinding is capable of very high accuracy and excellent surface finishes. Typical values are:

Dimensional tolerance:

• Common grinding operations: approx. ±0.005 mm (±0.0002 in)

• High-precision grinding: approx. ±0.001–0.003 mm (±0.00004–0.00012 in), depending on setup and environment

Surface roughness (Ra):

• General cylindrical grinding: approx. 0.2–0.8 µm Ra

• Fine grinding or superfinishing: approx. 0.05–0.2 µm Ra or better

Form and roundness accuracy can be controlled to within a few microns with suitable machines and fixturing.

Key Differences Between CNC Turning and CNC Grinding

Although both processes can machine cylindrical parts, their capabilities and ideal use cases differ. The following table summarizes the most important technical distinctions.

| Aspect | CNC Turning | CNC Grinding |

|---|---|---|

| Material removal mechanism | Single-point cutting tool shears chips | Abrasive grains on wheel remove tiny chips |

| Typical use stage | Roughing and semi-finishing | Finishing and superfinishing |

| Typical stock removal per pass | Up to several mm | Usually microns to tenths of a mm |

| Dimensional tolerance (typical) | Approx. ±0.020–0.050 mm; down to ±0.005–0.010 mm with fine turning | Approx. ±0.005 mm; down to ±0.001–0.003 mm in precision grinding |

| Surface roughness (Ra) | Approx. 0.4–3.2 µm Ra | Approx. 0.05–0.8 µm Ra |

| Suitable hardness range | Usually up to approx. 45–50 HRC for efficient machining | Effective for hardened materials 55–65 HRC and higher |

| Cycle time for large stock removal | Generally faster | Slower due to small depths of cut |

| Tooling | Insert-based tools (carbide, CBN, etc.) | Abrasive wheels (Al2O3, CBN, diamond, etc.) |

| Typical part types | General shafts, pins, bushings, flanges | High-precision shafts, bearing surfaces, hardened components |

| Setup and fixturing | Commonly chuck or collet; flexible | Often centers, chucks, or centerless setups with precise alignment |

| Impact on surface integrity | Risk of built-up edge, tool marks; usually low thermal damage | Needs control of burn, microcracks, residual stress via coolant and parameters |

| Cost per part (for large stock removal) | Usually lower | Usually higher due to slower removal and wheel costs |

When CNC Turning Is the Better Choice

CNC turning is generally the first choice for producing cylindrical components when the requirement is to remove significant material quickly and cost-effectively, and when tolerance and finish requirements are within the normal capabilities of turning.

1. Application criteria favoring CNC turning

CNC turning is usually preferred when:

• The part is rotationally symmetric and can be easily clamped.

• The material is in the soft or pre-hardened range where cutting speeds and tool life are acceptable.

• Stock removal requirements are high, such as reducing a bar or forging to near net shape.

• Dimensional tolerances are moderate, for example ±0.02–0.05 mm, and finishing by grinding is not strictly necessary.

• Surface finish requirements are in the range of approx. 0.4–1.6 µm Ra, which can be achieved by finish turning.

• Production volumes range from prototypes to medium or large batches, where cycle time and machine availability are important.

2. Typical part examples best suited for turning only

Examples of components commonly produced entirely by CNC turning include:

• General-purpose shafts for mechanical assemblies.

• Pins, spacers, and sleeves with moderate tolerance requirements.

• Pipe fittings, connectors, and threaded components.

• Flanges and hubs where surfaces are later welded or assembled without critical fit.

In these cases, using grinding would often increase cost and cycle time without providing significant functional benefit.

3. Economic considerations in favor of turning

From a cost perspective, CNC turning is usually more economical when:

• Material removal per part is high, allowing turning to exploit deeper cuts and higher feeds.

• Part tolerances and surface requirements do not justify a secondary grinding operation.

• Setup costs must be kept low for small batches or prototypes. A lathe setup is often faster and simpler than a grinding setup.

• Tooling costs can be managed with standard inserts and toolholders.

In many workflows, turning is used to achieve a near-net shape with sufficient stock left on critical surfaces for subsequent grinding only where required.

When CNC Grinding Is the Better Choice

CNC grinding becomes the preferred process when the part requires very tight tolerances, exceptional surface finishes, or finishing hardened materials after heat treatment.

1. Application criteria favoring CNC grinding

CNC grinding is usually selected when:

• Dimensional tolerances are in the range of ±0.005 mm or tighter, particularly for fitting components such as bearings or precision shafts.

• Surface finish must be better than approx. 0.4 µm Ra, such as for sealing surfaces, bearing journals, or sliding components.

• The part has undergone heat treatment, and hardness levels exceed typical turning capability (for example above 55 HRC).

• Roundness, cylindricity, or concentricity requirements are in the low micrometer range.

• The design demands low friction, low wear, or tight leakage control, which require superior surface integrity.

2. Typical part examples best suited for grinding

Parts where CNC grinding is often essential include:

• Bearing journals and races in automotive and industrial bearings.

• Precision spindle shafts for machine tools.

• Hydraulic and pneumatic cylinder rods with high sealing performance requirements.

• Hardened gear shafts, camshafts, and crankshafts requiring accurate lobes, journals, and shoulders.

• Fuel system components, such as injector bodies and plungers.

3. Surface integrity and functional performance

CNC grinding affects not only geometry and roughness but also surface integrity. Properly controlled grinding can produce:

• Low waviness and high roundness, improving running accuracy.

• Favorable residual stress profiles that enhance fatigue strength, if process parameters and coolant are controlled.

• Reduced micro-asperities that lower friction in sliding or rolling contact.

However, grinding must be carefully managed to avoid thermal damage (burn), surface cracks, or undesirable residual stresses. Suitable coolant flow, wheel selection, and dressing are essential to maintain consistent surface integrity.

Using CNC Turning and CNC Grinding Together

For many precision parts, the best solution is not turning or grinding alone, but a sequence combining both. This allows efficient material removal with turning and high-accuracy finishing with grinding.

1. Typical process flow: turning then grinding

A common manufacturing route for a precision shaft might be:

1) Rough turning: Remove bulk material to create basic diameters and shoulders, leaving machining allowance on critical surfaces.

2) Semi-finish turning: Improve accuracy and surface finish while still leaving a small allowance (for example 0.1–0.3 mm) on grinding surfaces.

3) Heat treatment: Hardening, tempering, carburizing, or nitriding to obtain required hardness and surface properties.

4) Stress relieving or straightening: Optional, to improve dimensional stability.

5) Finish grinding of journals and critical surfaces: Achieve final size, roundness, and surface finish requirements.

This combined approach balances throughput and precision. Turning takes advantage of high metal removal rates prior to heat treatment, while grinding corrects distortions and provides the final precision after heat treatment.

2. Allowances and datum strategy

When planning a turning-plus-grinding route, it is important to:

• Leave sufficient grinding allowance on surfaces to remove distortions introduced by heat treatment. Typical radial allowances can range from approx. 0.1 to 0.3 mm, depending on part size and heat treatment process.

• Establish clear datums (reference surfaces) during turning that will be used in grinding setups. For example, turning center holes and end faces that are later used between centers in cylindrical grinding.

• Control concentricity and runout between turned features so that subsequent grinding can easily bring all features within final tolerance.

Good datum management ensures that geometry relationships between surfaces remain consistent across turning and grinding operations.

3. Fixturing and setup considerations

To ensure accuracy when combining turning and grinding:

• Use center holes and drive dogs for shaft-type parts during both turning and grinding where possible, improving coaxiality.

• Ensure clamping forces do not distort thin-walled or slender parts during grinding, which could lead to out-of-round conditions.

• Monitor part temperature to minimize thermal expansion effects on measured dimensions, especially for tight tolerances.

Coordinated fixturing strategies help maintain alignment between processes and reduce rework.

Technical Factors to Consider When Choosing the Process

Deciding between CNC turning, CNC grinding, or a combination requires a structured evaluation of design, material, and production requirements.

1. Required tolerances and surface finish

One of the most decisive criteria is the required dimensional and surface quality:

• If tolerances are moderate (for example ±0.02–0.05 mm) and surface finish requirements are above approx. 0.4–0.8 µm Ra, turning can often satisfy the specification with proper tooling and parameters.

• If tolerances are tighter than ±0.01 mm or surface finish requirements are below approx. 0.4 µm Ra, grinding is usually necessary.

• For functional fits such as interference or transition fits, consider the maximum allowable deviation and whether turning can consistently achieve it under production conditions.

2. Material hardness and heat treatment condition

Material hardness strongly influences process selection:

• Soft to medium-hard materials (up to about 250–300 HB or approximately 30–35 HRC) can be efficiently turned with high cutting speeds.

• Pre-hardened or hard materials (above approx. 35–40 HRC) may still be turned with appropriate coated carbide or CBN tools, but tool wear and cost increase.

• Hardened surfaces above approx. 55 HRC are typically ground, as grinding maintains reasonable tool life and consistent results.

Heat treatment sequencing is important. If a part must be hardened for wear resistance, plan turning before heat treatment and grinding after, with allowances for distortion.

3. Part geometry, stiffness, and accessibility

Geometry affects feasibility and quality:

• Long, slender parts are more susceptible to deflection under cutting forces in turning, potentially leading to taper or chatter. Grinding forces are generally lower, which can help on slender parts when properly supported.

• Complex profiles with multiple diameters, shoulders, and undercuts may be faster to generate in turning. Grinding complex profiles may require special wheels or multiple setups.

• Internal features such as deep bores may require specialized boring bars in turning or small ID grinding wheels in grinding, each with their own limits on depth-to-diameter ratio.

Evaluate whether the required geometries are better suited to the flexibility of turning tools or the precision of grinding wheels.

4. Production volume and cycle time

Production volume and takt time affect choice:

• For low-volume prototypes and small batches, turning is often preferred because of lower setup time and simpler tooling.

• For high-volume series, centerless grinding or specialized cylindrical grinding can provide consistent, highly accurate parts, especially for standard diameters and lengths.

• When material removal requirements are high, turning reduces cycle time, and grinding is reserved only for final finishing steps.

Consider balancing equipment load: heavily loaded grinding machines should not be used for tasks that turning can accomplish more economically.

5. Dimensional stability and distortion

Some parts are prone to distortion due to residual stress, heat treatment, or geometry. In such cases:

• Rough and semi-finish turning leave an allowance to be corrected later.

• Interim stress-relief heat treatment may be applied after roughing.

• Final grinding corrects any distortions to achieve final dimensions and geometry.

If a part must maintain high stability in service, the residual stress state induced by turning or grinding and any subsequent treatments should be considered.

Cost and Productivity Comparison

Cost analysis is critical when deciding between CNC turning and CNC grinding. While grinding delivers higher precision, it may not be cost-effective for all surfaces or all parts.

1. Factors influencing process cost

Major cost elements for both processes include:

• Machine hourly rate: Grinding machines are often more specialized and may have higher hourly rates than standard CNC lathes.

• Cycle time: Turning usually offers shorter cycle times for large stock removal, while grinding time increases with tighter finish requirements.

• Tooling costs: Turning uses inserts, which must be replaced based on wear; grinding uses wheels that require periodic dressing and replacement.

• Setup and programming: Complex grinding geometries may require more programming and setup effort, especially for specialized wheels and fixtures.

• Inspection and quality assurance: Tighter tolerances achieved by grinding may require more detailed inspection, adding to overall time.

2. Typical process combinations for cost optimization

In many cost-optimized workflows:

• Turning handles roughing and semi-finishing on all surfaces.

• Only the most critical surfaces are ground, such as bearing seats, sealing surfaces, or reference diameters.

• Less critical surfaces are left in the turned condition, if this is acceptable for assembly and function.

This targeted approach allows resources to be concentrated where precision matters most, avoiding unnecessary grinding operations.

Practical Decision Guide: Turning, Grinding, or Both

To decide which process is right for your part, evaluate the following practical questions:

1) Part function and fit:

• Are there surfaces that serve as bearings, seals, or precision assembly interfaces? If yes, these likely require grinding or fine turning with closely controlled parameters.

2) Specification requirements:

• What are the tightest tolerances on diameter, roundness, and runout?

• What are the required surface roughness values for each feature?

3) Material condition:

• Is the part hardened or will it be hardened after machining?

• Is it made from a difficult-to-machine material that leads to high tool wear in turning?

4) Production constraints:

• What is the required output per shift or per day?

• What machines are available (turning centers, grinding machines, centerless grinders)?

5) Quality and reliability:

• How critical is dimensional consistency across large batches?

• Is there a risk of functional problems if tolerances or finishes are not met consistently?

By answering these questions for each critical feature of your part, you can determine whether CNC turning alone is sufficient, whether grinding is necessary, or whether a hybrid approach is optimal.

| Feature type | Typical requirement | Recommended process |

|---|---|---|

| Non-critical shaft diameter | Moderate tolerance, medium finish | CNC turning only |

| Bearing journal | Very tight tolerance, low Ra | Turning + cylindrical grinding |

| Internal bore for press fit | High dimensional consistency | Turning + ID grinding or reaming |

| Sealing surface | Low roughness, controlled waviness | CNC grinding or fine grinding |

| Threaded area | Standard tolerance | CNC turning (threading) only |

Common Pain Points and How Process Choice Addresses Them

In many machining operations, recurring issues can often be mitigated by appropriate use of turning and grinding.

1. Variation in critical diameters

Problem: Parts exhibit variability in diameter and roundness beyond acceptable limits, leading to assembly difficulties or inconsistent fits.

Mitigation:

• Use CNC turning for roughing and semi-finishing, then apply cylindrical grinding for final sizing of critical diameters.

• Implement stable fixturing between centers to ensure consistent concentricity.

2. Insufficient surface finish

Problem: Turned surfaces do not meet specified roughness, causing higher friction or leakage.

Mitigation:

• Optimize turning parameters (tool geometry, feed, cutting speed) to improve finish.

• When required Ra is below about 0.4 µm, apply grinding as the final process on relevant surfaces.

3. Rapid tool wear in hard materials

Problem: Turning hardened or abrasive materials leads to excessive tool wear and unstable dimensions.

Mitigation:

• Limit turning to pre-hardened stages and switch to grinding after heat treatment.

• Select suitable grinding wheel types (such as CBN for hardened steel) to achieve stable removal rates and quality.

Conclusion

CNC turning and CNC grinding are complementary processes for manufacturing high-quality cylindrical components. CNC turning offers high material removal rates, flexible geometry creation, and cost-effective production for a wide range of parts. CNC grinding provides superior dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and capability to handle hardened materials and critical surfaces.

In many practical cases, the optimal solution is a combined approach: turning for roughing and semi-finishing, followed by grinding on selected critical features after heat treatment. By carefully analyzing functional requirements, tolerances, surface finish targets, material hardness, and production volume, you can determine whether your part is best produced by turning, grinding, or a well-planned sequence of both processes.

Clear specification of requirements for each feature, thoughtful datum definition, and coordinated process planning between turning and grinding will help ensure that your parts meet performance expectations while maintaining cost efficiency and reliable production.

FAQ: CNC Turning vs CNC Grinding

Can CNC turning achieve the same precision as CNC grinding?

In most cases, CNC turning cannot consistently achieve the same level of precision and surface finish as CNC grinding, especially for very tight tolerances and low roughness requirements. Turning can reach tolerances around ±0.005–0.010 mm and surface roughness near 0.2–0.4 µm Ra under optimized conditions, but this often requires rigid machines, fine-tuned parameters, and stable materials. CNC grinding, especially cylindrical and centerless grinding, can routinely achieve tighter tolerances in the ±0.001–0.003 mm range and surface finishes below 0.2 µm Ra. For applications such as bearings, precision spindles, and sealing surfaces, grinding is usually preferred for final sizing and finishing.

Do all turned parts need to be ground afterward?

No, most turned parts do not require grinding. Many industrial components function reliably with turned dimensions and finishes if their tolerance and surface requirements fall within normal turning capabilities. Grinding is mainly used when particular surfaces must meet very tight dimensional tolerances, low roughness values, or must be finished after heat treatment. For non-critical features or parts with moderate requirements, adding a grinding operation would increase cost and lead time without significant functional benefit. It is common to grind only selected critical surfaces on a part and leave the remaining surfaces in the turned condition.

When should I plan heat treatment relative to turning and grinding?

A typical and effective sequence is to perform rough and semi-finish turning in the soft state, then apply heat treatment, and finally use grinding for critical surfaces. This approach leverages the high removal rate of turning before the material becomes hard while allowing grinding to correct any distortion caused by heat treatment and achieve final precision. In some cases, a small amount of turning or hard turning may still be performed after heat treatment, but for very hard materials and tight tolerances, grinding is usually the final step.

Is centerless grinding a replacement for CNC turning?

Centerless grinding is not a full replacement for CNC turning; instead, it is a specialized grinding method that complements turning in high-volume production of cylindrical parts. Centerless grinding excels at finishing long runs of small-to-medium-diameter parts with very consistent diameter, roundness, and surface finish. However, it is less flexible in producing complex profiles, shoulders, and large diameter variations along the part. In many workflows, bar stock is first cut and turned to near-net shape, and then centerless grinding is applied to specific diameters that require high accuracy and finish.