CNC marine machining is widely used to produce precise, corrosion‑resistant parts for boats, ships, offshore platforms and underwater systems. This guide explains the main machining features, common materials, performance requirements, production workflows, and cost structures specific to marine applications.

Overview of CNC Marine Machining

CNC marine machining is the use of computer numerical control (CNC) milling, turning, drilling and related processes to manufacture components that operate in seawater or marine environments. Typical parts include structural fittings, propulsion components, steering and motion systems, deck hardware, fluid handling components and underwater housings.

Compared with general industrial machining, marine parts must withstand continuous exposure to saltwater, cyclic loads, vibration, and often difficult maintenance conditions. As a result, CNC marine machining emphasizes dimensional consistency, sealing surfaces, corrosion resistance and robust surface treatments.

Typical Marine Components Made by CNC Machining

Marine systems use a wide variety of machined parts. Many of them are low‑to‑medium volume components that benefit from CNC flexibility and repeatability.

| Component Type | Typical Function | Main Machining Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Propeller hubs and blades (prototypes, small series) | Power transmission and thrust generation | 3D contoured surfaces, tight balancing, smooth surface finish |

| Propeller shafts and intermediate shafts | Transmit torque from engine to propeller | Long precision turning, straightness control, concentricity, keyways, spline machining |

| Rudder stocks, tiller arms, steering quadrants | Steering load transfer | High strength alloys, accurate hole patterns, bearing seats, fillets and radii |

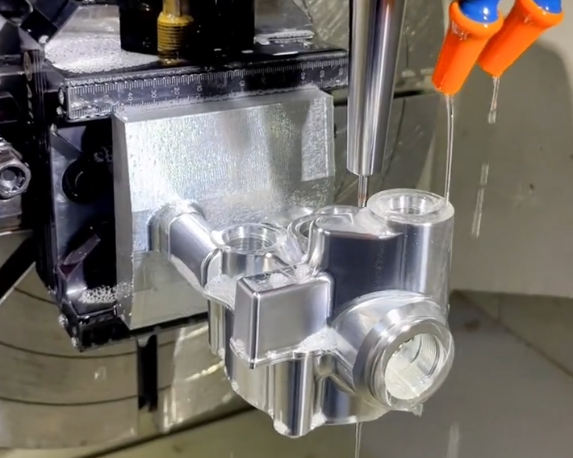

| Flanges, manifolds, valve bodies | Fluid transfer and control | Flat sealing faces, bolt circles, internal channels, threaded ports |

| Winch drums, capstan parts | Anchoring and mooring systems | Large diameter turning, groove machining, wear‑resistant surfaces |

| Deck cleats, fairleads, chocks and bollards | Line handling, mooring and towing | Robust designs, radiused edges, corrosion‑resistant materials and finishes |

| Engine brackets, mounts and subframes | Support and alignment of power units | Flatness, hole location accuracy, vibration resistance |

| Hydraulic cylinder components | Actuation for steering, cranes, ramps | Precision bores, rod ends, threads, sealing grooves |

| Underwater housings and enclosures | Protect sensors, electronics and optics | Accurate O‑ring grooves, flat sealing faces, controlled wall thickness |

| Instrumentation brackets and sensor mounts | Positioning of navigation and monitoring devices | Repeatable geometry, corrosion resistance, vibration stability |

Key Machining Features in Marine Applications

Marine parts typically combine several functional features that must be controlled precisely to ensure performance and safety.

Shafts and Rotating Features

Rotating elements such as propeller shafts, pump shafts and winch drums require attention to straightness, runout and surface finish.

- Diameter tolerances for bearing seats commonly fall within IT6–IT7 ranges, for example 20 mm f7 or h6 depending on fit.

- Total indicated runout (TIR) of critical journals is often specified at 0.02–0.05 mm for medium‑sized shafts.

- Shaft shoulders and fillets must be free of sharp transitions to reduce stress concentration; radii are commonly 0.5–3 mm depending on shaft size.

Flanges, Sealing Faces and Gaskets

Flange connections and sealing faces are widely used in piping systems, ballast systems, cooling circuits and hydraulic lines.

Key machining aspects include:

- Flatness of sealing faces, often specified at ≤0.05–0.1 mm across the full face for moderate diameters.

- Surface roughness of gasket faces in the Ra 1.6–3.2 μm range for many elastomeric or fiber gaskets, and Ra 0.8–1.6 μm where metallic gaskets are used.

- Accurate bolt circle diameters and bolt hole positions to match standard marine flanges and valves.

O‑Ring Grooves and Sealed Housings

Underwater housings and submerged connectors depend on correctly machined O‑ring grooves.

Common parameters are:

For a typical static O‑ring groove:

- Groove width: O‑ring cross‑section diameter plus 5–15% clearance, depending on material and pressure rating.

- Groove depth: designed to provide 15–30% squeeze on the O‑ring cross section.

- Surface finish: often specified at Ra ≤ 0.8–1.6 μm to avoid leakage paths and O‑ring damage.

Threads, Ports and Pipe Connections

Marine systems use various standard thread forms for pipe and hose connections, including NPT, BSPP, BSPT and metric threads.

Machining considerations include adequate thread engagement length, chamfering, thread relief and protective radii between threaded and unthreaded regions. Threads in corrosion‑prone areas are often machined with additional allowance for coatings or are sealed using compatible thread sealants.

Surface Finishes and Contact Surfaces

Surface roughness requirements vary by function:

- Bearing seats: Ra 0.4–0.8 μm to support stable lubrication and load transfer.

- Sliding and sealing surfaces: typically Ra 0.2–0.8 μm depending on sealing method and contact pressures.

- Non‑critical external surfaces: Ra 3.2–6.3 μm is common, especially if a thick coating or paint layer is applied later.

Materials for CNC Marine Machined Parts

Material selection is central to marine component performance. It affects corrosion resistance, strength, machinability and total cost.

Aluminum Alloys for Marine Use

Marine aluminum alloys offer a favorable strength‑to‑weight ratio and good corrosion resistance in seawater, particularly when anodized or painted.

Common alloys include:

5083 and 5086 are non‑heat‑treatable aluminum‑magnesium alloys often used for structural parts, brackets and hull fittings. They provide high corrosion resistance in seawater and good weldability. Tensile strength is typically in the 270–320 MPa range for 5083‑O/H111, depending on thickness.

6061‑T6 is widely used where higher strength and machinability are required but with somewhat reduced saltwater corrosion resistance compared with 5xxx series. It is often selected for machined brackets, instrument mounts and housings located above the waterline. Typical tensile strength is about 290–320 MPa in T6 temper.

Stainless Steels in Marine Environments

Stainless steels are used where higher strength or harder surfaces are needed, or where hardware is continuously wet or partially submerged.

Common grades include:

- 316 / 316L: molybdenum‑bearing austenitic stainless steel with improved pitting and crevice corrosion resistance in chloride environments compared with 304. Widely used for fasteners, fittings, shafts with moderate loads, and deck hardware.

- Duplex stainless steels (such as 2205): used when higher strength and enhanced corrosion resistance are required, for example in heavy‑duty shafts, components exposed to high chloride concentrations or higher temperatures.

When machining stainless steels, lower cutting speeds and suitable tool materials are necessary compared with aluminum. Coolant selection and flow are important to control heat and maintain tool life.

Bronze and Copper Alloys

Bronze and copper alloys are often used where excellent corrosion resistance and favorable tribological properties are needed.

Typical applications and alloys:

- Propellers: nickel‑aluminum bronze is commonly used for its strength, resistance to cavitation erosion and good corrosion performance in seawater.

- Bearings and bushings: tin bronze and phosphor bronze are used for plain bearings and sliding surfaces, often in combination with stainless steel or other hard shafts.

- Valve bodies and fittings: various bronze alloys provide corrosion resistance and castability, followed by CNC machining of critical faces and threads.

Titanium Alloys for Highly Demanding Components

Titanium is selected for high‑value components where weight reduction, high strength and extreme corrosion resistance justify the material and machining cost. Examples include parts for high‑speed craft, specialized underwater vehicles and high‑end hardware.

Common machining considerations include reduced cutting speeds, high‑performance tooling, and effective cooling to manage heat buildup and tool wear.

Engineering Plastics and Composites

Non‑metallic materials also appear in marine systems, especially for electrical insulation, weight reduction or low friction interfaces.

Examples include:

- Acetal (POM) for precision bushings, gears and low‑friction guides.

- Nylon and UHMW‑PE for wear pads, sheaves and slide surfaces.

- Glass‑filled polymers for structural brackets and housings in non‑submerged areas.

When machining plastics, controlling cutting temperature and avoiding burrs are important to maintain dimensional accuracy and clean edges.

Dimensional Tolerances for Marine CNC Parts

Marine component tolerances are tailored to each function, balancing manufacturing cost against performance and assembly requirements.

General Dimensional Tolerances

For many non‑critical marine parts, tolerances consistent with ISO 2768‑m (medium) or similar practice are used. This typically includes linear tolerances on the order of ±0.1–0.3 mm for general dimensions, depending on nominal length.

Fits for Shafts and Housings

Rotating components rely on defined fits between shafts, bearings and housings. Typical ranges include:

- Press fits and interference fits for couplings and bearing outer rings, using tolerance combinations such as H7/p6 or H7/n6.

- Sliding or clearance fits for removable couplings and sliding bushings, for example H7/g6 or H8/f7 depending on required clearance and shaft diameter.

Correct selection of tolerances helps minimize vibration, wear and fretting corrosion while still allowing assembly and maintenance.

Geometric Tolerances

Geometric tolerances are important for marine parts that must maintain alignment and seal integrity.

- Cylindricity and circularity to ensure accurate bearing contact and sealing.

- Parallelism and perpendicularity to maintain alignment between connected components, such as flanges and shafts.

- Position tolerances for bolt holes and dowel holes to ensure interchangeability and consistent assembly across series production.

Surface Finishing and Corrosion Protection

CNC machining defines the base geometry and finish, but marine parts generally require additional treatments to withstand saltwater and mechanical wear.

Mechanical Finishing Processes

Common mechanical finishing options include:

- Deburring: removal of sharp edges and burrs from machined parts to reduce injury risk and improve corrosion performance.

- Grinding: applied to bearing seats, shafts and sealing faces to achieve tight tolerances and good surface finish (for example Ra ≤ 0.4 μm).

- Polishing: used on propellers and underwater housings to reduce drag, minimize fouling points and improve visual quality.

Chemical and Electrochemical Treatments

Chemical treatments increase corrosion resistance and provide a suitable base for coatings.

- Anodizing of aluminum: often specified as Type II or hard anodizing for components requiring enhanced wear resistance. Thickness is typically in the 10–50 μm range depending on application.

- Passivation of stainless steels: removes free iron from the surface and promotes formation of a uniform passive layer, improving resistance to pitting and general corrosion.

- Phosphating and similar treatments for carbon steels used in protected locations or as pre‑treatment before painting.

Paints, Coatings and Plating

Coatings are selected according to exposure conditions (above waterline, splash zone, full immersion, internal fluid contact).

- Marine paints and epoxy coatings: applied to aluminum and steel structures for long‑term protection. Coating systems may include primer, intermediate and topcoat layers.

- Zinc‑rich primers and metallic coatings: used for sacrificial protection of steel in many marine contexts.

- Nickel and chrome plating: sometimes used on stainless steel shafts and wear surfaces to improve hardness and wear resistance, with careful consideration of hydrogen embrittlement and adhesion requirements.

Production Workflows and Process Planning

Effective CNC marine machining relies on clear process planning, considering material behavior, part geometry and downstream treatments.

CAD/CAM Preparation and Design Review

Digital design data is the foundation of marine machining. Step files, native CAD files or technical drawings are imported into CAM software to generate toolpaths.

Before machining, typical design reviews examine:

- Material specification and availability in required bar, plate or forging formats.

- Wall thickness and transitions to avoid distortion and stress risers.

- Locations of critical sealing surfaces, O‑rings and threads, verifying tolerances and finishes.

- Allowance for coatings, anodizing or plating thickness where dimensions must be maintained.

Fixturing and Workholding for Marine Parts

Marine components often have irregular shapes, large dimensions or long overhangs. Workholding solutions may include custom fixtures, steady rests and tailstocks.

Key objectives are controlling deflection, maintaining alignment across setups and providing access to all critical surfaces. Proper fixture design also helps preserve surface finish by reducing vibration.

Machining Strategies for Large and Long Parts

Long shafts and large flanges require careful machining strategies:

- Multiple support points using steady rests for long shafts to limit deflection.

- Progressive roughing and semi‑finishing passes to balance residual stresses, followed by finishing cuts at stable conditions.

- Symmetrical material removal on both sides of plates or rings to minimize warping, especially for high‑strength alloys.

Quality Control and Inspection

Inspection ensures that CNC marine parts meet drawing requirements before assembly and marine certification processes.

- Dimensional inspection using calipers, micrometers and bore gauges for basic dimensions.

- Coordinate measuring machines (CMM) for complex profiles, bolt patterns, 3D surfacing and geometric tolerances.

- Surface roughness measurement for sealing surfaces, bearing areas and sliding interfaces.

- Pressure or leak testing on housings and flanged assemblies, where required by design or classification rules.

Typical Issues and Considerations in Marine Machining

Marine components must function reliably in a demanding environment. Several technical considerations influence machining decisions.

Corrosion at Mating Surfaces and Assemblies

Contact between dissimilar metals in seawater can cause galvanic corrosion. Design and machining must consider material combinations, contact area, surface finish and potential coatings. Using appropriate isolating materials, sealants or compatible fasteners helps reduce this issue.

Dimensional Stability in Service

Temperature variations and continuous loading can affect dimensional stability. Machining strategies may include stress‑relief heat treatment for certain steels and controlled material removal sequences to minimize internal stresses. For critical shafts, straightness checks after rough machining and before finishing are common.

Maintainability and Replacement

Marine components often need to be replaced or serviced in confined spaces. CNC machining supports maintainability by providing consistent dimensions and fits across batches, facilitating the use of standardized spare parts and simplifying removal and installation procedures.

Cost Factors in CNC Marine Machining

Cost evaluation for marine parts combines material cost, machining time, tooling, finishing and quality control. Because many parts are custom or low volume, detailed cost analysis helps optimize design choices.

| Cost Factor | Influence on Price | Typical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Material type and size | High impact | Marine‑grade alloys and large stock sizes increase raw material and waste cost. |

| Part complexity | High impact | 3D contours, multiple features, tight tolerances and multiple setups lengthen machining time. |

| Tolerance and surface finish | Medium to high impact | Tighter tolerances and smoother finishes require slower feeds, special tooling and additional operations. |

| Quantity and batch size | Medium impact | Larger batches distribute setup and programming cost across more parts, reducing unit cost. |

| Special fixtures and tooling | Medium impact | Custom fixtures, form tools and long‑reach tooling add up‑front cost that is recovered over production volume. |

| Secondary processes | High impact | Anodizing, passivation, painting, plating and grinding increase both lead time and unit cost. |

| Inspection and documentation | Medium impact | Detailed measurement reports, CMM inspection and certification documentation add labor time. |

| Lead time and scheduling | Medium impact | Urgent jobs with tight deadlines may require overtime or schedule changes, increasing cost. |

Material and Stock Utilization

Marine‑grade materials are often more expensive than standard industrial grades. Stock is commonly purchased in bar, plate or forged forms with additional thickness or diameter to allow for machining allowance and potential distortion.

Optimizing part nesting, cutting plans and raw stock selection can reduce waste and total material cost. For long shafts, cutting to appropriate rough lengths and planning center drilling for support can improve utilization.

Machining Time and Programming Effort

Machining time is driven by feed rates, toolpaths, number of operations and tool changes. Complex 3D surfaces and deep cavities increase cycle time. Accurate CAM programming, optimized toolpaths and the use of multi‑axis machines can reduce cycle times, but they add initial programming effort.

Tooling, Inserts and Tool Life

Marine materials such as stainless steel, nickel‑aluminum bronze and titanium require appropriate cutting tools and inserts. Tool wear affects both part quality and cost. Tooling strategy must balance cutting parameters, tool life and time spent on tool changes and offsets.

Secondary Treatments, Coatings and Assembly

After machining, many marine parts require treatments that add both cost and lead time. Planning logistics for an external coater or in‑house finishing line, along with intermediate inspections, is important. Assembly operations, such as fitting bearings or installing threaded inserts, further contribute to total cost.

Cost Optimization Strategies

Cost can be controlled without compromising function if design, material and process choices are aligned.

Design for Machinability

Early collaboration between designers and machinists allows modifications that simplify manufacturing. Examples include using standard radii and chamfers, avoiding unnecessarily deep pockets, selecting standard thread sizes and consolidating features where possible. The objective is to reduce machining time and setups while preserving functional performance.

Selecting Appropriate Tolerances

Tolerances should be as tight as necessary but not tighter. Assessing where functional requirements truly demand high precision can avoid over‑specification. Non‑critical surfaces and features can use broader tolerances and standard fits, which reduce machining time, tool wear and inspection requirements.

Batching and Standardization

Grouping similar components, standardizing dimensions across multiple designs and planning production in batches improve efficiency. Reusing programs, fixtures and inspection plans decreases preparation effort and speeds up delivery of replacement or spare parts.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is CNC marine machining?

CNC marine machining is the precision manufacturing of marine and offshore components using CNC equipment, designed to meet the high strength, corrosion resistance, and reliability requirements of marine environments.

Which materials are commonly used in CNC marine machining?

Common materials include carbon steel, alloy steel, stainless steel, bronze, aluminum alloys, and corrosion-resistant materials suitable for seawater environments.

Why is corrosion resistance important in CNC marine machining?

Marine components are exposed to seawater, humidity, and salt spray, making corrosion resistance critical for ensuring long service life, safety, and reduced maintenance costs.

What surface treatments are recommended for machined marine parts?

Typical treatments include anodizing for aluminum, passivation for stainless steel, epoxy or polyurethane coating systems for steel and aluminum structures, and plating or hard coatings where wear resistance is necessary. Treatment selection depends on material, operating environment (above or below waterline, immersion time) and mechanical load conditions.