Automation CNC machining combines numerically controlled machine tools with automated handling, monitoring, and data systems to produce parts with minimal manual intervention. This page provides a systematic overview of technologies, workflows, materials, tolerances, surface finishes, and cost models so that engineers, buyers, and plant managers can plan, evaluate, and operate automated CNC systems effectively.

Fundamentals of Automation in CNC Machining

Automation CNC machining starts from conventional CNC technology and extends it with automatic handling, integrated sensors, and data-driven control. The objective is consistent quality, predictable lead times, and stable unit cost across varying production volumes.

Key concepts include:

- Numerical control of multi-axis machine tools using G-code or similar formats.

- Automated loading and unloading of workpieces, tools, and pallets.

- Integrated measurement and feedback for closed-loop or semi-closed-loop control.

- Centralized data management for tooling, offsets, scheduling, and traceability.

Automation can be applied to milling, turning, turn-mill, grinding, EDM, and drilling. It may range from simple bar feeders on lathes to fully integrated flexible manufacturing systems (FMS) with pallet pools, automated guided vehicles, and centralized cell control.

Core Components of an Automated CNC System

An automated CNC machining setup is a combination of machine tools, peripherals, and control software. Understanding each layer allows better selection and integration.

CNC Machine Tools

The CNC machine is the central hardware element. For automation purposes, several technical characteristics are particularly relevant:

- Stable, rigid structure for repeatable results under continuous operation.

- High-speed servo drives and spindles to shorten cycle time.

- Adequate axis configuration (3, 4, 5 or more axes) to reduce setups.

- Robust automatic tool changer (ATC) with enough tool capacity for unattended jobs.

Typical machine categories include vertical machining centers (VMCs), horizontal machining centers (HMCs), multi-axis machining centers, CNC lathes with or without sub-spindles and live tooling, and grinding or EDM machines.

Robotic and Automatic Loading Systems

Robotic automation covers the transfer of raw stock and finished parts. Common elements are:

Robotic arms: Used for bin picking, machine tending, and transfer between stations. Configurations can be articulated robots, SCARA, or collaborative robots. Selection criteria include payload, reach, repeatability, and integration interface with CNC controllers.

Part feeders: These include conveyors, vibratory bowls, gravity chutes, and flexible feeders with vision systems. Their role is to present parts in consistent position and orientation for the robot or machine.

Bar feeders and gantry loaders: Specialty systems for turning centers that automatically feed bar stock or handle workpieces between spindle and storage locations.

Palletization and Workholding Systems

Pallet and workholding systems are key for repeatable positioning and minimal setup time. Typical technologies:

- Zero-point clamping systems with precise locating features.

- Modular vises, tombstones, and fixture plates tailored to families of parts.

- Pallet pools and automatic pallet changers that queue up multiple jobs.

For automated operation, workholding should support consistent loading, robust clamping force monitoring where possible, and minimal manual adjustment between jobs.

Tool Management and Automatic Tool Changers

Tool management in automation CNC machining has several dimensions:

Automatic tool changers (ATCs) must be reliable, fast, and have sufficient capacity. Magazine capacities can range from 20 tools in smaller machines to more than 200 in complex cells. Tool holders must be standardized across machines where possible to simplify logistics.

Tool presetting may be done off-line using dedicated measuring devices to capture tool length, diameter, and runout. This data is transferred to CNC controls to reduce setup time. Tool life management, tool sistering, and automatic replacement strategies are crucial for stable unattended operations.

Monitoring, Sensors, and Data Interfaces

Automated systems rely on sensors and data connectivity for predictable output. Typical sensors and data points include:

Spindle load, vibration signals, coolant pressure and level, door and safety interlocks, part presence switches, and tool breakage detection mechanisms. Probing systems allow automated zero-point setting, in-process measurement of dimensions, and comparison to tolerances.

Machine connectivity is often achieved via Ethernet-based protocols. Data may be collected for runtime, downtime, alarms, and part counters. This enables analysis of cycle time and machine utilization.

CNC Programming and Workflow for Automated Cells

Automation requires a disciplined workflow from CAD model to finished part. Programming and data management are central to this.

CAD/CAM Integration and Post-Processing

Most automated CNC machining uses CAD/CAM suites to generate toolpaths. Parametric models and feature-based machining strategies can help standardize operations. Post-processors translate toolpaths into machine-specific G-code, taking into account kinematics, tool changers, and available cycles.

For automation, consistent post-processor templates are important to ensure predictable tool call patterns, safe retract positions, and standardized probing cycles where used.

G-Code Structure and Safety Logic

Automated systems operate without constant human supervision, so G-code must be structured for robustness. Common practices include:

- Clear separation of setup, machining, and end-of-cycle sequences.

- Use of safe start blocks to initialize modal states (units, coordinate systems, plane selection, feed modes).

- Standardized reference positions for tool change and robot access.

- Automatic part clamping and unclamping commands integrated into programs.

Many controllers support macros and parametric programming. These can encapsulate common operations, such as probing routines or multi-part patterns, reducing programming time and variability between jobs.

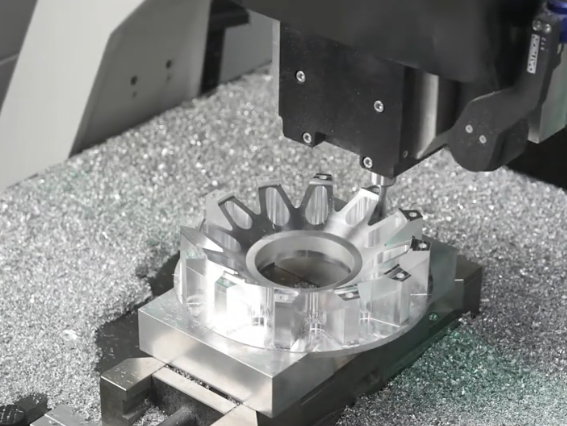

Tool Path Strategies in Automated Production

Toolpath strategies influence cycle time, tool wear, and stability. In automated cells, consistent and predictable tool wear is often prioritized. This leads to selection of conservative cutting parameters balanced with acceptable cycle time. Toolpaths may be optimized for chip evacuation and thermal stability, especially during long unattended runs.

Batch-oriented programming for multiple parts on a fixture or pallet is common. Programs might address each part location systematically using work coordinate system offsets or parametric loops.

Materials for Automation CNC Machining

Material selection affects tool life, achievable tolerances, and overall cost. Automated CNC machining is applied to metals, plastics, and specialized alloys. Properties like hardness, toughness, thermal conductivity, and abrasiveness influence process parameters.

| Material Type | Common Grades | Characteristics Relevant to Automation | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum alloys | 6061, 6082, 7075, 2024 | High machinability, good chip formation, low cutting forces, moderate tool wear | Consumer products, housings, automotive, aerospace structural parts |

| Carbon steels | 1018, 1045, 4140 | Moderate hardness, predictable tool life, good strength; requires suitable coolant | Shafts, fasteners, fixtures, machinery components |

| Stainless steels | 304, 316, 17-4PH | Austenitic grades can cause work hardening; heat generation and tool wear must be controlled | Chemical processing, food equipment, medical, marine hardware |

| Tool steels | D2, O1, H13 | High hardness, significant tool wear; requires rigid machine and robust tooling | Molds, dies, wear-resistant inserts and tooling |

| Titanium alloys | Ti-6Al-4V | Low thermal conductivity, high strength; demands sharp tools, rigid setups, controlled heat | Aerospace, medical implants, high-performance components |

| Nickel-based superalloys | Inconel 718, Hastelloy C-276 | High-temperature strength, strong work hardening; tool life and heat management are critical | Gas turbines, aerospace hot sections, chemical equipment |

| Copper alloys | Brass (C360), bronze | Good machinability in free-cutting grades, smear tendencies in some alloys | Fittings, connectors, valves, electrical components |

| Engineering plastics | POM (Delrin), PEEK, PTFE, Nylon | Low cutting forces, possible heat-related deformation, careful fixturing needed | Insulators, medical devices, fluid handling components |

Material Behavior and Process Stability

For automated machining, the stability of the process over long runs is essential. Material batches with variable hardness or inclusions can disrupt tool life predictions and increase scrap. Consistent supply of certified material, with known mechanical and metallurgical properties, is preferred.

Abrasive materials such as some cast irons or fiber-reinforced composites cause accelerated tool wear, requiring well-defined tool life management and possibly more frequent inspection cycles within the automated process.

Tolerances and Dimensional Control

Automated CNC machining can achieve tight tolerances provided that machine condition, environment, and process design are controlled. Tighter tolerances typically require more measurement and compensation in the automated loop.

Linear and Geometric Tolerances

Linear tolerances in automated CNC machining commonly range from ±0.05 mm down to ±0.005 mm, depending on machine capability, material, tool, and environmental control. For more critical features, tighter tolerances are achievable with suitable setups and machines designed for precision.

Geometric dimensioning and tolerancing (GD&T) such as position, flatness, perpendicularity, and concentricity are controlled through careful fixturing and coordinated machining strategies. Multi-axis machines can minimize re-clamping, reducing stack-up of fixture errors.

Thermal Effects and Compensation

Extended unattended operation causes temperature variations in machine structures, spindles, and tools. These variations can result in dimensional drift. Measures to manage this include:

- Machines with built-in thermal compensation models and temperature sensors.

- Stable shop temperature and isolated heat sources where feasible.

- Warm-up cycles before precision machining sequences.

In-process probing can detect drift and trigger automatic offset adjustments. For some applications, periodic calibration cycles are inserted between batches.

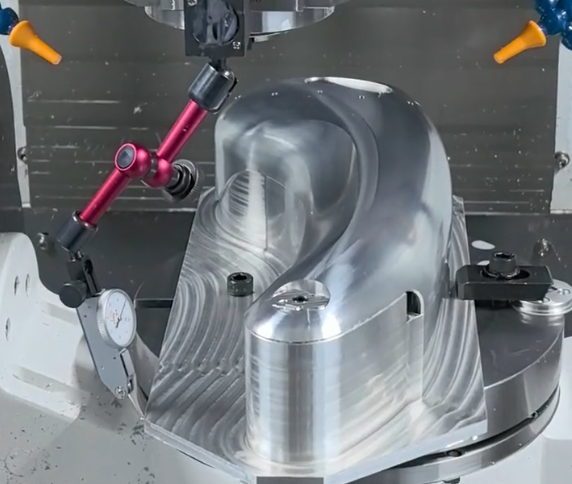

Measurement Integration and Feedback

Automation CNC machining often uses probing for:

Workpiece location: Probing establishes zero references, corrects for fixture tolerances, and supports multi-part setups.

Feature verification: Critical dimensions may be measured during machining. When deviations are detected, the machine adjusts tool offsets or flags a part for inspection or rejection.

Tool measurement: In-machine tool setting or laser measurement monitors tool length, diameter, and breakage. This supports automatic tool changeover to sister tools when limits are reached.

Surface Finish in Automated CNC Machining

Surface finish is determined by tool geometry, feed rate, spindle speed, toolpath strategy, and machine vibration characteristics. Automated systems often target consistent surface finish within specified roughness ranges across long production runs.

| Operation Type | Typical Ra Range (µm) | Notes on Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Rough milling | 3.2 – 12.5 | Optimized for material removal; automated cells monitor load and tool wear |

| Semi-finish milling | 1.6 – 3.2 | Prepares surfaces for final passes; consistent toolpath and coolant supply are important |

| Finish milling | 0.4 – 1.6 | Involves lower feed per tooth and sharp tools; wear tracking is crucial for stability |

| Finish turning | 0.4 – 1.6 | Requires stable cutting conditions and balanced workholding |

| Fine finishing / superfinishing | 0.1 – 0.4 | Often achieved with grinding, honing, or polishing in dedicated steps |

Tooling and Cutting Parameters

Surface finish in automated machining depends on insert radius or end mill cutter geometry, feed per tooth and step-over, cutting speed, and depth of cut. Cutting data must be tuned to each material and tool combination. For stable automation, conservative parameters may be chosen to maintain surface finish across the full tool life rather than only at the beginning.

Coated carbide, cermet, ceramic, and polycrystalline diamond (PCD) tools are common for different material groups. Tool manufacturers provide recommended ranges, and these are adjusted based on machine stiffness and coolant type.

Vibration and Chatter Control

Chatter introduces irregular surface marks and dimensional variation. In automated environments, chatter problems need to be minimized by design:

- Use of stable tool overhang ratios and rigid tool holders.

- Optimized engagement angles and step-over to avoid tool resonance.

- Selection of cutting speeds outside of chatter-prone ranges.

Some controls support adaptive control functions that adjust feed based on spindle load, which can reduce chatter risk in variable cutting conditions.

Automated CNC Cell Layout and Workflow

Beyond individual machines, automation CNC machining often uses cells or lines. Layout and workflow design influence productivity, flexibility, and changeover time.

Cell Configurations

Common layouts include:

Single machine with robot: A robot loads and unloads a machine, presents parts to a deburring or washing station, and transfers finished parts to packaging or inspection. This setup is suitable for moderate volumes and variable part types.

Multi-machine cell: Multiple CNC machines are arranged around a shared robot or robot rail. The robot may serve as the central logistics unit, moving parts between machines, washing, and inspection steps.

Pallet-based FMS: Machines connect to a pallet pool. Parts are clamped to pallets offline, and the system schedules pallets to machines based on priorities and available tools. This enables high mix production with minimal manual intervention.

Material Flow and Buffering

Material flow needs defined buffer zones to avoid starvation or overflow. Storage racks for raw material, in-process parts, and finished goods must be sized according to cycle times and shift patterns. Buffering reduces sensitivity to small disruptions, such as tool changes or short stoppages.

Clear identification methods such as barcodes or RFID tags allow automated tracking of part status and identification in multi-part flows. This supports traceability and correct routing through different operations.

Quality Control Integration

Quality control in automated CNC systems may be integrated at several levels:

- In-machine probing for critical features on each or selected parts.

- Inline or near-line measurement systems that receive parts automatically.

- Random or scheduled sampling directed to coordinate measuring machines (CMMs).

Measurement results can feed back to machining centers via offset adjustments or triggers for tool change. Automated feedback loops help maintain quality without continuous manual inspection.

Cost Structure of Automation CNC Machining

Costs in automation CNC machining consist of capital investment, operating expenses, and overhead. Understanding cost components enables realistic budgeting and pricing.

Capital Expenditures (CapEx)

CapEx includes machine tools, robots, fixtures, sensors, and integration. Major elements are:

CNC machines: Cost scales with size, axis count, precision, and special functionalities. Multi-axis machining centers and turn-mill machines typically carry higher prices but may reduce the number of machines required.

Automation hardware: Robots, grippers, vision systems, conveyors, bar feeders, pallet systems, and automated doors are included here. Complexity and payload capacity significantly influence cost.

Integration and engineering: Mechanical design, robot programming, PLC programming, safety systems, and commissioning add to the initial investment. Custom fixtures and grippers for each part family are part of this category.

Operating Expenses (OpEx)

Operating costs are incurred during production runs and maintenance. Important categories:

- Labor: Operators, programmers, maintenance technicians, and quality staff.

- Tooling: Inserts, end mills, drills, holders, and presetting activities.

- Energy: Electricity for machines, compressors, and coolant systems.

- Consumables: Coolants, lubricants, cleaning agents, and filters.

- Maintenance: Spare parts, scheduled servicing, and unscheduled repairs.

Automated systems aim to spread fixed labor and capital costs over more machine hours by enabling extended unattended operation. Tooling and maintenance practices must support this operating model.

Cost Drivers in Automated CNC Machining

Total cost per part depends on cycle time, scrap rate, machine utilization, and batch size. Major drivers:

Cycle time is influenced by cutting parameters, toolpath optimization, machine acceleration, and tool change times. Automation reduces non-cutting time associated with loading and unloading.

Setups and changeovers affect the proportion of nonproductive time. Standardized fixtures and program templates can shorten changeover. Automation magnifies the benefit of fewer changeovers by allowing longer uninterrupted runs.

Scrap and rework costs include material waste, machining time lost, and capacity used by reworked parts. Stable processes with monitoring and measurement integration tend to reduce this component.

Planning and Implementing Automated CNC Machining

Implementing automation requires structured planning and phased execution. Aligning technical decisions with production requirements is essential.

Defining Requirements and Scope

Before selecting equipment, it is necessary to define:

- Part families, annual volumes, and required flexibility.

- Tolerances, surface finish, and material mix.

- Available floor space, power supply, and environmental conditions.

- Integration needs with existing planning and quality systems.

This data guides the selection of machine type, number of spindles, degree of automation, and level of measurement integration.

Equipment and Supplier Selection

Selection criteria include machine accuracy and capacity, control compatibility across machines and robots, available options for probes, tool setters, and interfaces, expected support for commissioning and service, and the ability of suppliers to provide documentation and training.

CNC control capabilities should support the required macros, data interfaces, and safety functions. Robots and peripheral equipment must integrate with the CNC via digital I/O, fieldbus, or dedicated middleware.

Workflow Design and Documentation

Consistent workflows minimize errors during unattended operation. Documentation should cover part routing and operations sequence, fixture and tool identification, G-code naming conventions and revision control, robot programs, and safety logic.

Standard operating procedures for setup, changeover, and restart after stoppages provide a reference for operators and maintenance teams. Clear, structured documentation contributes to stable long-term operation.

Common Operational Considerations in Automated CNC Machining

During actual operation, several practical issues must be managed to keep automated cells productive and reliable.

Chip Management and Coolant Handling

Continuous machining generates large volumes of chips. Effective chip conveyor systems and chip bins are needed to avoid blockages and heat buildup. Coolant filtration and replenishment are important for consistent cutting conditions and tool life.

Automated systems often incorporate level sensors for coolant tanks and chip bins. These can trigger alarms or scheduled interventions, allowing maintenance tasks to be grouped efficiently.

Tool Life Management

Unattended machining depends on predictable tool life. Tool life management typically involves:

- Preset life in number of parts, cutting time, or distance.

- Monitoring of cutting load or torque where available.

- Automatic switching to sister tools when limits are reached.

- Regular review of wear patterns to adjust life thresholds.

Tool identification codes and centralized tool databases help track usage across machines and jobs. This reduces unexpected tool failures and associated downtime.

Maintenance and Reliability

Automated systems operate for extended hours, so preventive maintenance is essential. Typical actions include lubrication, filter replacement, coolant system cleaning, alignment checks, verification of safety devices and interlocks, and testing of measurement systems and probes.

Spare parts strategies ensure that critical components such as pumps, encoders, and tool changers have reasonable availability. Maintenance records and alarm histories guide improvements in schedules and procedures.

Typical Use Cases and Application Scenarios

Automation CNC machining is used in various industries and production volumes. A few common scenarios illustrate the range of applications.

High-Volume Production of Similar Parts

In automotive or consumer goods production, large batches of similar or identical parts are machined. Automation focuses on high throughput, short cycle times, and minimal variation. Dedicated fixtures and optimized toolpaths are common, and robots or gantry systems handle parts at high speed.

High-Mix, Medium-Volume Manufacturing

In job shops or contract manufacturing for multiple customers, part variety is high while volumes per part are moderate. Flexible pallets, standardized fixtures, and modular tool libraries enable frequent changeovers. Scheduling software and FMS controllers are used to assign pallets and tools dynamically to machines.

Precision Components in Regulated Industries

Aerospace and medical industries require traceability and documented quality. Automated CNC cells can embed measurement, logging, and data retention for each part. Tight tolerances and surface finishes are combined with automatic recording of key process parameters.