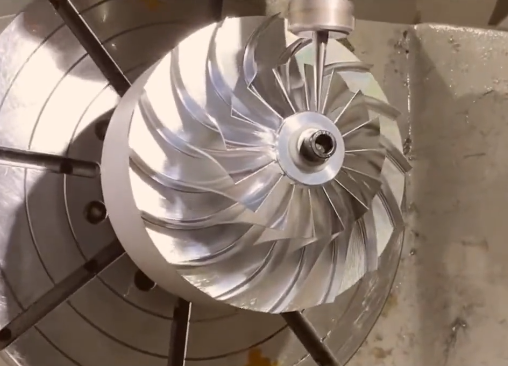

Aluminum is a primary material for CNC machining, turning, milling, drilling, and high-speed cutting due to its low density, high specific strength, good corrosion resistance, and favorable machinability. Selecting the correct alloy and temper directly affects dimensional accuracy, tool life, surface finish, mechanical performance, and overall cost. This guide provides a systematic, technical overview of aluminum machining materials and selection methods for engineering and manufacturing teams.

Fundamentals of Aluminum for Machining

Aluminum is a non-ferrous, lightweight metal with a density around 2.7 g/cm³, approximately one-third that of steel. It exhibits good thermal and electrical conductivity and forms a stable oxide film that contributes to corrosion resistance. For machining, several fundamental properties are especially important:

- Strength and hardness relative to required loads and wear

- Machinability, chip formation, and tool wear behavior

- Dimensional stability during and after machining

- Surface finish quality reachable with standard tools

- Corrosion resistance, weldability, and anodizing capability

Pure aluminum is soft and ductile but has low strength, so engineering applications almost always use aluminum alloys. Alloying elements (such as magnesium, silicon, copper, zinc, and manganese) and thermomechanical treatments substantially modify mechanical properties and machining responses.

Main Aluminum Alloy Series for Machining

Wrought aluminum alloys for machining are typically classified by 4-digit series based on the principal alloying elements. Each series has characteristic property ranges and machinability profiles.

1xxx Series (Commercially Pure Aluminum)

1xxx series alloys (e.g., 1050, 1100, 1200) contain at least 99.0% aluminum. They offer excellent corrosion resistance, high electrical and thermal conductivity, and very good formability, but relatively low strength.

For machining, 1xxx series alloys are soft and gummy, often leading to built-up edge on cutting tools and less favorable surface finish at high material removal rates. They are used where electrical conductivity or chemical resistance is critical, such as in bus bars, chemical equipment, and heat exchangers, rather than where tight tolerances under load are required.

2xxx Series (Aluminum-Copper Alloys)

2xxx series alloys (e.g., 2011, 2014, 2024) use copper as the primary alloying element. They offer high strength and good fatigue resistance. Many grades are heat-treatable to further enhance mechanical properties.

From a machining standpoint, free-machining grades such as 2011-T3 are known for excellent chip breaking and dimensional control, making them suitable for high-speed automatic screw machines and high-volume turned parts. However, copper-containing alloys typically have lower corrosion resistance and may require protective coatings, anodizing, or additional corrosion-control measures in service.

3xxx Series (Aluminum-Manganese Alloys)

3xxx series alloys (e.g., 3003, 3103) use manganese as the main alloying element. They provide moderate strength, good formability, and good corrosion resistance. These alloys are widely used in general-purpose sheet and plate but are less common for precision machined components that require high strength or tight tolerances.

Their machinability is generally lower than that of 5xxx or 6xxx series; chips tend to be more continuous, and surface finish is less predictable. They are more often fabricated by forming and welding than by heavy machining operations.

5xxx Series (Aluminum-Magnesium Alloys)

5xxx series alloys (e.g., 5052, 5083, 5754) rely on magnesium as the principal alloying element and are non-heat-treatable. They are known for high corrosion resistance, especially in marine and chloride environments, along with good weldability and moderate to high strength.

Machinability is fair to good, depending on specific grade and temper. These alloys are common in marine, transportation, and pressure vessel applications. When machining thick plate or complex geometries, attention to heat generation and distortion is important due to their relatively high thermal expansion and lower elastic modulus compared to steels.

6xxx Series (Aluminum-Magnesium-Silicon Alloys)

6xxx series alloys (e.g., 6060, 6061, 6082, 6063) contain magnesium and silicon, which form Mg2Si. These heat-treatable alloys provide a balance of strength, corrosion resistance, weldability, and machinability. They are among the most widely used series for machined structural components.

6061-T6 and 6082-T6, in particular, are common choices for CNC-milled and turned parts, fixtures, and structural components. They exhibit relatively consistent machining behavior, good chip formation with appropriate cutting parameters, and compatibility with anodizing and other surface treatments.

7xxx Series (Aluminum-Zinc Alloys)

7xxx series alloys (e.g., 7005, 7050, 7075) use zinc as the primary alloying element, often with magnesium and copper. Heat treatment yields very high strength and good fatigue resistance, making these alloys important in aerospace and high-performance structural applications.

7075-T6 is a frequently specified alloy for high-strength machined components. Machinability is generally good, especially in higher-strength tempers, but higher cutting forces and tool wear should be expected compared with 6xxx alloys. Corrosion resistance, particularly stress-corrosion cracking, must be evaluated based on environment and temper.

Common Machining Aluminum Alloys and Typical Properties

| Alloy / Temper | Series | Typical Yield Strength (MPa) | Typical Ultimate Strength (MPa) | Brinell Hardness (HBW) | Relative Machinability | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011-T3 | 2xxx | ~275 | ~350 | ~95 | Very high | High-volume turned parts, connectors, fasteners |

| 2024-T351 | 2xxx | ~325 | ~470 | ~120 | Good | Aerospace structural parts, fittings |

| 5052-H32 | 5xxx | ~193 | ~228 | ~60 | Fair | Sheet metal parts, enclosures, marine components |

| 5083-H111 | 5xxx | ~145 | ~290 | ~75 | Fair | Shipbuilding, pressure vessels, cryogenic tanks |

| 6061-T6 | 6xxx | ~275 | ~310 | ~95 | Good to very good | General-purpose machined components, fixtures |

| 6082-T6 | 6xxx | ~260 | ~310 | ~90 | Good | Structural parts, machinery components |

| 7075-T6 | 7xxx | ~505 | ~570 | ~150 | Good | Aerospace parts, high-load mechanical components |

| 7075-T73 | 7xxx | ~435 | ~510 | ~135 | Good | Components requiring high SCC resistance |

Values above are representative and vary by product form, exact specification, and supplier. Always consult material standards and certificates for design-critical values.

Temper Designations and Their Effect on Machining

Temper designations (such as O, H32, T6) describe the specific combination of cold work and heat treatment that an alloy has undergone. This strongly influences hardness, strength, residual stresses, and machining response.

Annealed and As-Fabricated Tempers

O-temper (annealed) indicates the alloy has been fully softened, providing maximum ductility and minimum strength. Machining very soft tempers can lead to built-up edge, smeared surfaces, and long, stringy chips. However, low hardness reduces cutting forces and can extend tool life if chip control is properly managed.

As-fabricated tempers (F) are supplied with no special control over strain-hardening or heat treatment. Properties and machining behavior may be less consistent, so they are less common where dimensional control is critical.

Strain-Hardened Tempers

H tempers (e.g., H32, H34) are applied to non-heat-treatable alloys (such as 5xxx and some 3xxx). They are produced by cold working, sometimes followed by partial annealing. Higher H numbers generally correspond to higher strength and hardness, which can improve chip fragmentation and surface definition but increase cutting forces.

For machining, moderate strain-hardened tempers often provide a useful balance between chip control and tool load. Excessive strain hardening may lead to localized work hardening at the cutting edge and accelerated tool wear during interrupted cuts.

Heat-Treated Tempers

T tempers (e.g., T4, T5, T6, T73) apply to heat-treatable alloys (2xxx, 6xxx, 7xxx). A T6 temper generally represents solution heat treatment followed by artificial aging to reach near-maximum strength. These tempers are widely used for machined parts because they provide consistent strength and dimensional stability.

Higher-strength T tempers typically result in better chip control but require more robust tooling and machine rigidity. Overaged tempers such as T73 may slightly reduce strength but improve toughness and environmental resistance, which is important for 7xxx alloys exposed to stress-corrosion environments.

Key Material Properties Influencing Machinability

Machinability is not defined by a single property but is the combined effect of several material characteristics that govern chip formation, cutting forces, tool wear, and surface texture. For aluminum alloys, the following properties are especially relevant:

Strength and Hardness

Higher strength and hardness generally increase cutting force and tool wear but can improve chip breaking and surface definition. Soft alloys may smear, generating poor surface finish at high speeds unless tool geometry and cutting conditions are optimized.

In many practical applications, medium-strength tempers provide efficient machining with a predictable finish and reasonable tool life. Strength should be matched to functional loads rather than maximized by default, to avoid excessive machining effort.

Ductility and Work Hardening

Ductility influences chip shape. Highly ductile, low-strength alloys tend to form long, continuous chips. This can interfere with automatic chip evacuation and may cause surface scratches and tool damage if chips are not controlled. Work-hardening behavior affects the stability of the cutting zone; minimal work hardening is generally favorable for consistent machining in aluminum.

Thermal Conductivity and Expansion

Aluminum has high thermal conductivity, which can help dissipate heat from the cutting zone. However, it also has a relatively high coefficient of thermal expansion. During high-volume material removal, heat accumulation can cause temporary dimensional changes, particularly in slender or thin-walled parts.

Controlling cutting parameters, using appropriate coolants, and planning machining sequences (such as roughing and finishing in separate stages) help mitigate thermal distortion and maintain tighter tolerances.

Microstructure and Inclusions

Microstructural features such as second-phase particles, intermetallics, and grain size influence cutting behavior. Alloys with well-dispersed, fine precipitates often cut more cleanly than those with coarse or brittle intermetallic particles that can cause micro-chipping of cutting edges.

Cleanliness (low levels of hard inclusions and contaminants) is important to preserve tool edges and achieve consistent surface roughness, especially in high-speed machining operations and fine finishing passes.

Machining Performance of Common Aluminum Alloys

Different alloys exhibit distinct machining profiles. Understanding typical performance characteristics supports rational alloy selection and process planning.

2011 Aluminum

2011 is widely known as a free-machining aluminum alloy. It often contains small additions of bismuth and lead that enhance chip breaking and reduce tool wear. It is especially suitable for high-speed turning and automatic screw machine applications.

Advantages include very short, well-controlled chips, high achievable productivity, and good dimensional accuracy. Limitations include lower corrosion resistance compared with 5xxx and 6xxx alloys and restricted use in food or medical applications where lead-containing alloys may not be allowed by regulatory standards.

2024 Aluminum

2024, particularly in T3 or T351 temper, offers high strength and good fatigue performance and is common in aerospace structures. Machinability is generally good when cutting parameters and tool geometry are optimized. Chips typically break readily, and the alloy can produce fine surface finishes.

Since 2024 contains copper, it is more prone to corrosion and often requires protective coatings or cladding in corrosive environments. Post-machining anodizing or painting is therefore common in aerospace components.

5052 and 5083 Aluminum

5052 is often specified for sheet and plate applications requiring good corrosion resistance and moderate strength, especially in marine and transport sectors. Machinability is moderate; chips may be less well broken, and careful control of tool sharpness is required to avoid smearing and burr formation.

5083 is used for high-strength, welded, corrosion-resistant structures such as ship hulls and pressure vessels. Machining thick 5083 plate requires attention to heat generation, tool selection, and fixturing, since distortion can occur in large parts with uneven material removal.

6061 and 6082 Aluminum

6061-T6 is one of the most frequently machined aluminum alloys. It combines good strength, corrosion resistance, weldability, and consistent machining behavior. It is suitable for a broad range of parts, from mechanical brackets and housings to tooling and fixtures.

6082-T6 is commonly used in structural applications requiring slightly higher strength than 6061 in some markets. Its machining performance is similar, though local availability and standards may determine which is more common in a given region.

7075 Aluminum

7075-T6 provides very high strength and is widely used in critical aerospace and high-load mechanical components. It generally machines well, producing good surface finishes and manageable chips when appropriate cutting tools are used.

Due to its high strength, cutting forces and tool wear are higher compared with 6xxx alloys. When corrosion resistance, particularly stress-corrosion cracking resistance, is important, tempers such as 7075-T73 may be specified at some cost to strength but with improved environmental performance.

Selection Criteria for Aluminum Machining Alloys

Choosing an aluminum alloy for a machined component involves balancing mechanical performance, machinability, environmental resistance, manufacturability, and cost. The following criteria are commonly evaluated.

Mechanical Requirements

Target properties include yield strength, ultimate strength, elastic modulus, hardness, and fatigue resistance. Applications with dynamic or cyclic loading, such as aircraft components, require particular attention to fatigue and fracture properties.

For many general-purpose mechanical parts, 6xxx series alloys provide sufficient strength with favorable machining performance. Very high structural demands may require 2xxx or 7xxx alloys, while highly corrosion-resistant, welded structures may favor 5xxx alloys.

Environmental and Corrosion Resistance

The service environment determines minimum corrosion performance. Marine and chloride-rich environments favor 5xxx alloys. Where galvanic coupling to other metals occurs, potential differences and contact conditions must be evaluated.

When using 2xxx or 7xxx alloys in aggressive environments, protective measures such as anodizing, conversion coatings, or paint systems should be integrated into the design and production plan.

Dimensional Tolerance and Stability

Thin walls, long slender features, and tight tolerances place greater demands on dimensional stability. Residual stresses from rolling, extrusion, or heat treatment can relax during machining, causing distortion.

To mitigate this, stress-relieved tempers or specially processed plate and bar may be specified. Process strategies can include symmetrical material removal, intermediate stress relief, roughing with a machining allowance, and final finishing after stabilization.

Surface Finish and Aesthetic Requirements

Visible parts require uniform surface appearance both before and after finishing. Alloys designed for anodizing or with controlled microstructure can provide consistent visual outcomes. High-silicon or highly alloyed grades may show more pronounced contrast in anodized surfaces compared with 6xxx alloys with balanced composition.

When a very fine surface finish is needed, alloy choice, temper, tool geometry, and cutting conditions must be aligned. In many cases, 6061-T6 and similar alloys are selected because they can reach low roughness values with standard finishing passes.

Cost and Availability

Cost factors include raw material price per kilogram, yield (material utilization), machinability (affecting cycle time and tool consumption), and any secondary operations required (heat treatment, finishing, inspection). Availability in required forms (bar, plate, extrusions, forgings) and dimensions is also critical.

6xxx and 5xxx alloys are generally more readily available in a wide range of stock sizes compared with specialized aerospace-grade 2xxx and 7xxx alloys, which may have longer lead times and stricter procurement conditions.

Machining Strategies and Parameters for Aluminum Alloys

Optimized machining of aluminum requires careful selection of cutting parameters, tools, and process sequences. Although exact values depend on machine capabilities and specific materials, several general principles apply to most aluminum CNC operations.

Cutting Speeds and Feeds

Aluminum allows relatively high cutting speeds due to its thermal conductivity and low hardness. Typical cutting speeds for carbide tools may range from several hundred to over 1,000 m/min in milling, depending on alloy, cutter diameter, and machine rigidity. Feed rates can be correspondingly high to maintain proper chip load and avoid rubbing.

Lower-strength alloys need particular attention to feed rate; too low a feed can cause built-up edge, while too high a feed may lead to chatter or dimensional errors. Adjustments should be based on observed chip forms and measured surface finish.

Tool Materials and Coatings

Carbide tools are standard for most aluminum machining operations. Uncoated or polished tools are often used to avoid adhesion and to maximize sharpness at the cutting edge. However, certain coatings specifically designed for aluminum, such as diamond-like carbon (DLC) or specialized low-friction coatings, can reduce built-up edge and extend tool life.

High-speed steel (HSS) tools may still be used for lower-speed operations, drilling, and reaming, but carbide tools typically provide better productivity and longer life in continuous CNC production environments.

Tool Geometry and Chip Control

Effective chip control is essential for stable and automated machining. Positive rake angles, appropriate relief, and large flute spaces promote free-cutting behavior and chip evacuation. Helix angle and chip breakers should be chosen to produce short or easily evacuated chips without compromising tool strength.

In drilling and deep pocketing operations, chip evacuation is a primary constraint. Optimized flute design, periodic pecking cycles, or through-tool coolant can be necessary to prevent chip packing and tool breakage.

Coolant and Lubrication

Coolant strategies range from dry machining to flood coolant and minimum quantity lubrication (MQL). For aluminum, flood coolant often improves surface finish and tool life while assisting chip removal. However, certain high-speed operations can be performed dry or with MQL, especially when tools and cutting conditions are optimized for low friction.

Coolants and lubricants must be compatible with downstream processes such as anodizing or adhesive bonding. Residual films should not interfere with surface preparation steps.

Workholding and Fixturing

Due to aluminum’s relatively low modulus and high thermal expansion, workholding must prevent part deformation while allowing for efficient tool access. Fixtures should be rigid, but clamping forces must be controlled to avoid permanent distortion or localized marks, especially on thin-walled parts.

Vacuum fixtures, soft jaws, and dedicated support features are common solutions. For highly precise components, fixturing strategies often include multiple setups, reference datums, and relevant inspection steps to ensure geometry is maintained throughout machining.

Dimensional Stability and Residual Stress Management

Residual stresses in aluminum products arise from casting, rolling, extrusion, quenching, and straightening processes. During machining, removal of material can release these stresses, causing distortion, warping, or twisting. Managing these effects is essential for tight-tolerance parts.

Source of Residual Stresses

Residual stresses may be tensile or compressive and vary through the thickness of plate or bar. Quenched heat-treatable alloys can show higher near-surface stresses, while rolled or extruded products have stress patterns related to deformation history and cooling gradients.

Non-uniform machining, where one side or region is heavily machined before the opposite side, can trigger distortion. Complex shapes with asymmetrical material removal are particularly susceptible.

Material and Process Measures

To improve dimensional stability, stress-relieved plate or bar can be specified, especially for thick sections and parts with large machined cavities. Some suppliers offer “precision plate” or “machining plate” with controlled residual stress levels.

Process measures include roughing to leave an allowance, allowing the part to stabilize (sometimes with intermediate stress relief), and then performing finishing cuts. Symmetrical machining patterns and balanced removal from opposite sides can also reduce distortion.

Inspection and Compensation

For critical components, intermediate inspection after roughing may reveal trends in distortion. In some cases, machining strategies are adjusted, or minor design modifications are made to compensate. Precision fixturing and reference features also improve repeatability when small distortions must be controlled tightly.

Surface Quality, Burr Control, and Finishing

Surface quality influences component performance, fatigue life, and appearance. For aluminum, attaining consistent surface roughness and minimizing burrs are key concerns in machining.

Surface Roughness Considerations

Surface roughness depends on tool geometry, feed rate, cutting speed, depth of cut, and machine stability. Aluminum can support low roughness values (e.g., Ra < 0.8 μm) with appropriate finishing passes and sharp tools. Very fine finishing operations may use specialized end mills, wiper inserts, or honing tools.

Directionality of feed marks may influence sealing surfaces, sliding contact areas, or aesthetic surfaces. Where necessary, tool path strategies can be adapted to orient marks in non-critical directions or to minimize visible artifacts.

Burr Formation and Removal

Burr formation is a common issue in aluminum machining, particularly at exit edges of drilled holes and milled features. Burrs can interfere with assembly, sealing, or functional performance. They also add manual or automated deburring operations, which impact overall cost and lead time.

Controlling burrs starts with optimized cutting parameters and tool geometries. Techniques include modified edge preparation, specific entry/exit strategies, and dedicated chamfering or deburring passes within the CNC program. Where necessary, secondary processes such as brushing, vibratory finishing, or thermal deburring may be used.

Post-Machining Surface Treatments

Aluminum parts are often anodized, painted, plated, or chemically treated. These finishes provide corrosion resistance, wear resistance, and sometimes enhanced aesthetics. Anodizing requires careful control of alloy composition and surface preparation to achieve consistent color and thickness.

Machined surfaces must be adequately cleaned and degreased before finishing. Residual coolant, cutting oils, or embedded particles can affect coating adhesion and uniformity. Specifications for conversion coatings, anodic films, and paint systems should be integrated with material selection from the outset.

Application-Oriented Alloy Selection Examples

While each design is unique, typical application categories can guide initial alloy choices, which are then refined based on detailed requirements.

Aerospace Structures and Components

Aerospace applications frequently use 2xxx and 7xxx series alloys, especially 2024, 7050, and 7075, for load-bearing structures, fittings, and mechanical components. When machining these alloys, emphasis is placed on controlling distortion in large, thin-walled parts, achieving high surface integrity, and managing fatigue-critical features such as fastener holes and radii.

Process documentation, traceability, and conformity to aerospace standards and certificates are integral parts of material selection and machining planning.

Automotive and Transportation Parts

Automotive and general transportation components often rely on 5xxx and 6xxx series alloys due to their combination of strength, corrosion resistance, and formability. Machined parts can include chassis elements, brackets, housings, and suspension components.

High-volume production emphasizes cycle time, tool life, and automation. Alloys with good machinability and stable supply are typically selected, and machining centers are configured with standardized tools and fixtures to maintain consistency over large production runs.

Marine and Offshore Components

Marine structures and components, such as hull sections, deck hardware, and structural supports, often use 5xxx alloys like 5083 and 5456 for welded assemblies. Machined elements may be integrated into fabricated structures or produced as separate precision parts.

Material selection prioritizes corrosion resistance in saltwater environments, weldability, and fatigue performance in the presence of cyclic wave or vibration loads.

Precision Machinery and Tooling

Fixtures, jigs, machine frames, and automation components frequently use 6061-T6 and similar 6xxx alloys. These alloys provide adequate stiffness and strength while being straightforward to machine and readily available in plate, bar, and extrusion forms.

Where higher stiffness or wear resistance is necessary for local features, inserts of harder alloys or steel may be combined with aluminum structures to optimize cost and weight.

Comparison of Selected Alloys for Typical Machining Use Cases

| Use Case | Recommended Alloy(s) | Key Selection Reason | Machining Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-volume turned fittings | 2011-T3 | Very high machinability and productivity | Short chips, good dimensional control, assess lead content requirements |

| General structural bracket | 6061-T6 or 6082-T6 | Balanced strength, corrosion resistance, machinability | Stable machining, good surface finish, suitable for anodizing |

| High-strength aerospace component | 7075-T6 or 7050-T7451 | Very high strength and fatigue resistance | Higher cutting forces, control of distortion and surface integrity |

| Marine structural part | 5083-H111 | Excellent corrosion resistance and weldability | Moderate machinability, attention to distortion and burr control |

| Precision machine base plate | 6061-T651 machining plate | Stress-relieved plate with good dimensional stability | Suitable for heavy milling and tight tolerances |

Practical Issues in Aluminum Machining and Mitigation

In production environments, several recurring technical issues can affect machining performance and part quality. Recognizing these pain points and planning mitigation measures is essential for efficient and stable operations.

Built-Up Edge and Surface Defects

Built-up edge occurs when material adheres to the cutting edge, altering geometry and causing surface tearing or roughness. It is more common in softer alloys and at low cutting speeds or improper feeds. Mitigation strategies include using sharp tools with positive rake, optimizing cutting speed and feed, and applying appropriate coolant or lubrication.

Chip Evacuation in Deep Cavities and Holes

Poor chip evacuation can cause tool breakage, surface damage, and dimensional errors. Deep pockets, blind holes, and small-diameter drilling operations are particularly prone to chip packing. Solutions include tailored tool geometries with optimized flute design, through-tool coolant, peck drilling cycles, and tool paths that allow chips to be cleared between passes.

Distortion in Thin-Walled Parts

Thin-walled housings, enclosures, and ribs can distort during or after machining due to residual stress release or thermal effects. Effective measures include selecting stress-relieved material, applying symmetric machining strategies, using multiple lighter passes instead of heavy cuts, and controlling clamping forces with well-designed fixtures.

Burrs on Edges and Cross Holes

Burrs are common at exit edges of drilled holes, intersecting passages, and milled profiles. They can interfere with assembly, sealing, or fluid flow. Mitigation involves tuning cutting parameters, employing specialized deburring tools integrated into CNC programs, or applying secondary deburring methods. Including chamfers and deburring allowances in design drawings facilitates efficient burr removal plans.

Systematic Approach to Alloy Selection for Machined Parts

A structured selection process helps align material choice with performance, manufacturability, and cost objectives. A typical approach includes the following steps:

1) Define Design Requirements

Clarify all functional requirements, including loads, stiffness, weight limits, environmental conditions, expected life, acceptable deflection, and safety factors. Define key dimensions and tolerances, surface finish needs, joining methods, and any regulatory or certification constraints.

2) Shortlist Candidate Alloy Series

Based on strength, corrosion environment, and fabrication route (welded vs. non-welded), identify feasible alloy families. For example, 5xxx and 6xxx for general structural components, 2xxx and 7xxx for high-strength aerospace components, and specific free-machining alloys for high-volume turning.

3) Evaluate Machinability and Process Capability

For each candidate alloy, assess machinability, available stock forms and sizes, and compatibility with existing machine tools, cutting tools, and fixtures. Consider cycle time, tool wear rates, achievable tolerances, and any additional operations needed such as heat treatment or stress relief.

4) Confirm Surface Treatment and Compatibility

Determine required surface treatments, such as anodizing or painting, and confirm that the candidate alloys perform reliably with those processes. Evaluate appearance, coating adhesion, and corrosion performance after finishing.

5) Optimize for Cost and Supply Chain

Compare material cost, availability, procurement lead time, and supplier qualifications. Factor in overall process cost, including machining, finishing, inspection, and potential scrap rates. Select the alloy and temper that best satisfy technical requirements while supporting efficient, stable production.

Conclusion

Aluminum alloys offer a broad combination of lightweight, strength, machinability, corrosion resistance, and cost-effectiveness. Selecting the appropriate alloy and temper for machining requires a systematic evaluation of mechanical requirements, environmental conditions, surface finish needs, and manufacturing constraints. By understanding the characteristics of major alloy series, the effects of temper on machining behavior, and the practical aspects of chip control, tool selection, and dimensional stability, engineers and manufacturers can choose aluminum grades that support reliable, repeatable machining processes and durable, high-performance components.