Titanium and its alloys combine high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility, making them critical in aerospace structures, medical implants, and demanding industrial components. Precision titanium machining enables the production of complex, high-accuracy parts that fully utilize these material properties.

Material Characteristics of Titanium Relevant to Machining

The behavior of titanium during machining is governed by its physical and mechanical properties, which differ significantly from steels and aluminum alloys. Understanding these characteristics is essential for designing parts and selecting machining parameters.

Key Physical and Mechanical Properties

| Property | Commercially Pure Ti (Grade 2) | Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) | Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Grade 23) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ≈ 4.51 | ≈ 4.43 | ≈ 4.43 |

| Ultimate Tensile Strength (MPa) | ≈ 350–450 | ≈ 900–1,000 | ≈ 860–950 |

| Yield Strength (MPa) | ≈ 275–340 | ≈ 830–900 | ≈ 795–860 |

| Elongation (%) | ≈ 20–30 | ≈ 10–14 | ≈ 12–16 |

| Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | ≈ 103 | ≈ 114 | ≈ 114 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) | ≈ 16 | ≈ 6–7 | ≈ 6–7 |

| Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (µm/m·°C) | ≈ 8.6 | ≈ 8.6–9.0 | ≈ 8.6–9.0 |

Low thermal conductivity concentrates heat at the cutting zone, increasing tool wear and affecting surface integrity. The relatively low modulus of elasticity promotes part deflection, which must be considered in fixturing and toolpath strategies.

Machinability Considerations

Titanium is regarded as a difficult-to-machine material compared with aluminum or free-cutting steels. Key aspects include chip control, tool wear mechanisms, and thermal effects on the cutting edge. Process planning must balance cutting speed, feed rate, depth of cut, and coolant delivery to maintain dimensional stability and surface quality.

Titanium Alloys Used in Aerospace, Medical, and Industrial Fields

Different sectors employ specific titanium grades to meet mechanical performance, corrosion resistance, and regulatory requirements. Proper alloy selection affects machinability, achievable tolerances, and inspection strategies.

Aerospace Titanium Alloys

Aerospace structures require high strength at reduced weight, fatigue resistance, and compatibility with composite and metallic assemblies. Common alloys include:

- Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5): Widely used for structural components, brackets, fittings, and engine parts; good balance of strength and machinability.

- Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo and related near-alpha alloys: Used in high-temperature engine components with moderate machinability.

- Beta and near-beta alloys such as Ti-10V-2Fe-3Al: Applied in landing gear and heavily loaded parts, typically more demanding to machine.

Aerospace applications frequently call for high-precision pockets, thin walls, and large aspect-ratio features, requiring optimized tool paths and rigid setups.

Medical Titanium Alloys

Medical implants and instruments rely on titanium’s biocompatibility and corrosion resistance in bodily fluids. Typical materials include:

- CP Titanium (Grades 1–4): Used in dental implants and some orthopedic devices; comparatively easier to machine than high-strength alloys.

- Ti-6Al-4V ELI (Grade 23): Low interstitial version of Grade 5 with enhanced fracture toughness and fatigue performance; standard for load-bearing implants such as hip stems, knee components, and spinal devices.

Medical machining emphasizes fine surface finishes, tight dimensional control, and strict contamination avoidance. Burr-free features and traceable manufacturing documentation are critical.

Industrial Titanium Alloys

Industrial environments often involve aggressive media, elevated temperatures, and cyclic loading. Common use cases include:

- CP Titanium Grade 2: Heat exchangers, chemical processing equipment, and corrosion-resistant fasteners.

- Ti-6Al-4V: High-performance valves, pump impellers, and offshore components.

- Specialized alloys: Designed for high temperature or specific corrosion environments (e.g., chloride-rich or sour service), often requiring specialized machining strategies.

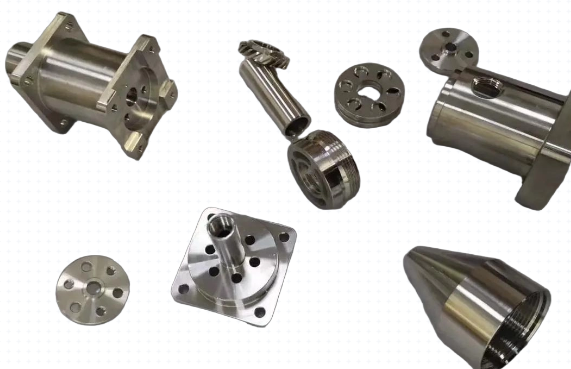

Industrial components can range from simple flanges to complex impellers, requiring consistent machining performance over varied batch sizes.

Precision Machining Methods for Titanium Components

Precision titanium parts are produced using a combination of subtractive and non-conventional processes. Selection depends on geometry, tolerance requirements, surface integrity, and production volume.

CNC Turning and Mill-Turn Machining

CNC turning is widely used for cylindrical components such as fasteners, shafts, and surgical screws. Multi-axis mill-turn centers allow complete machining in a single setup, improving concentricity and eliminating re-clamping errors.

Typical aspects of titanium turning include:

Use of sharp, positive-rake carbide inserts; moderate cutting speeds; and generous coolant flow to evacuate heat and chips. For thin-walled aerospace bushings or medical housings, controlled tool engagement and optimized support (steady rests, tailstocks, or custom fixtures) limit deformation.

3-Axis and 5-Axis CNC Milling

Complex prismatic and freeform geometries in titanium are usually machined by 3-axis and 5-axis CNC milling centers. 5-axis machining is particularly beneficial for:

Maintaining constant tool engagement on curved surfaces, minimizing tool deflection, and reaching intricate features with shorter, more rigid tools. This is fundamental for aerospace structural components with deep pockets and for contoured orthopedic implants.

High-speed machining strategies may be applied with lower radial engagement and higher feed rates, improving tool life and maintaining temperature control in the cutting zone.

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM)

Wire EDM and sinker EDM are used for titanium when the geometry is difficult or uneconomical to produce using conventional cutting tools. Examples include intricate internal profiles, sharp internal corners, and deep narrow slots.

EDM offers high accuracy and fine surface finish, with minimal mechanical loads on the part. However, it introduces a recast layer and heat-affected zone that may require removal for critical aerospace or medical surfaces, depending on specification.

Drilling, Tapping, and Hole-Making Operations

Hole-making in titanium demands careful control of feed and speed, along with high-pressure coolant. For small-diameter holes used in medical devices or aerospace hydraulic systems, peck drilling cycles and micro-lubrication can improve chip evacuation.

Thread formation can be carried out by tapping or thread milling. Thread milling frequently improves thread quality, tool life, and reduces the risk of tap breakage, which is particularly important in high-value aerospace and implant components.

Dimensional Tolerances and Geometric Accuracy

Precision titanium machining must achieve stringent tolerances for fit, function, and interchangeability. The combination of titanium’s low modulus and heat buildup requires tailored strategies to meet geometric specifications.

Common Tolerance Ranges

Typical tolerance ranges for machined titanium components include:

General dimensions for structural aerospace components: ±0.05 mm to ±0.1 mm; high-precision features: ±0.005 mm to ±0.02 mm. Medical implants often demand close control of mating surfaces in the ±0.01 mm range, with critical joint geometries sometimes specified tighter depending on the design and regulatory requirements.

Cylindricity, flatness, and positional tolerances are controlled using GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) to ensure functional alignment and proper load distribution.

Influence of Fixturing and Toolpath Strategy

Rigid fixturing is essential to minimize deflection during machining. Balanced clamping, optimized support points, and well-planned sequence of operations reduce stress accumulation and deformation when material is removed.

Toolpath strategy must account for the release of residual stresses in the material. Symmetrical machining, progressive roughing, and finishing passes at stable temperatures help to maintain dimensional stability. For thin-walled aerospace parts, it is common to rough both sides alternately and leave a uniform stock allowance for final finishing.

Surface Finish and Surface Integrity Requirements

Surface finish of titanium parts affects fatigue life, corrosion performance, osseointegration in implants, and sealing capability of mating surfaces. Surface integrity extends beyond roughness values to include microstructure, residual stress, and potential surface contamination.

Typical Surface Roughness Values

| Application | Typical Ra Range (µm) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aerospace structural surfaces | 0.8–3.2 | General brackets and fittings; critical aerodynamic surfaces may be lower. |

| Hydraulic sealing surfaces | 0.2–0.8 | Enhanced sealing and reduced leakage paths. |

| Orthopedic joint surfaces (pre-polish) | 0.1–0.4 | Followed by mechanical polishing or other finishing steps. |

| Surgical instruments | 0.4–1.6 | Balance of cleanability, aesthetics, and grip. |

| Heat exchanger and industrial surfaces | 1.6–6.3 | Roughness adjusted according to process requirements. |

These ranges vary with customer specifications and applicable standards. Consistent and repeatable surface finish is achieved by stable tool conditions, appropriate cutting parameters, and controlled tool wear.

Surface Integrity and Post-Machining Treatments

Machining can induce residual stresses, micro-cracks, and work hardening near the surface. For high-reliability applications, surface integrity is evaluated by methods such as microhardness testing, microscopy, and sometimes X-ray diffraction.

Common post-machining treatments include:

Fine grinding and lapping for tight flatness and roughness requirements; mechanical polishing of implant surfaces; and deburring processes (mechanical, abrasive flow, or controlled manual methods) to remove sharp edges without compromising dimensions.

For medical components, cleaning and passivation steps remove contaminants and help ensure a clean surface chemistry compatible with biological environments.

Tooling, Cutting Parameters, and Coolant Management

Tool selection and cutting conditions strongly influence efficiency, precision, and tool life in titanium machining. The correct combination minimizes heat concentration and maintains stable cutting forces.

Cutting Tool Materials and Geometry

Carbide tools are widely used for titanium machining, with coatings optimized for high-temperature resistance and reduced friction. For high-precision finish operations, uncoated or finely honed tools may be preferred to achieve superior surface quality.

Tool geometry typically includes positive rake angles and sharp cutting edges to reduce cutting forces and heat generation. Strong edge support and optimized chip breakers help maintain edge stability and control chip flow.

Cutting Speeds, Feeds, and Depth of Cut

Recommended cutting data for titanium are generally lower than for aluminum and many steels. Strategies often involve:

Moderate cutting speeds to limit temperature rise, sufficient feed per tooth to avoid rubbing, and controlled depth of cut to maintain constant engagement. Radial engagement is kept relatively low for high-speed milling strategies to allow heat dissipation through the chip.

Stable and predictable tool wear is preferred over aggressive parameters that may cause sudden tool failure and surface damage, especially in high-value aerospace and medical components.

Coolant Delivery and Chip Evacuation

Efficient coolant management is essential due to titanium’s low thermal conductivity. High-pressure, directed coolant nozzles assist in transporting heat away from the cutting zone and break chips into manageable segments.

For drilling deep holes in titanium, through-tool coolant is particularly effective. Inadequate cooling can lead to thermal softening of the tool, built-up edge, and dimensional drift. Chip evacuation is equally important to prevent re-cutting and surface damage.

Quality Control, Inspection, and Traceability

Precision titanium machining for aerospace, medical, and industrial sectors requires rigorous quality control. Inspection activities confirm that manufactured parts comply with dimensional, material, and documentation requirements.

Dimensional and Geometric Inspection

Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMM) are widely employed to verify dimensions, geometrical tolerances, and complex 3D shapes. Contact probes and scanning heads provide accurate data on critical features, including profiles, holes, and alignment.

Optical and non-contact methods, such as laser scanners and vision systems, can supplement CMM measurements, especially for freeform implant surfaces or large aerospace structures where full coverage is required.

Material Verification and Surface Examination

Material verification ensures that the correct titanium grade and mechanical properties are used. Methods include:

Spectroscopic analysis for chemical composition, hardness testing for mechanical consistency, and in some cases ultrasonic or radiographic inspection for internal defects in critical aerospace components.

Surface examinations may involve roughness measurement with contact profilometers or optical devices, microscopic evaluation of surface integrity, and, for implants, verification of surface cleanliness and passivation effectiveness.

Documentation and Traceability

Traceability links each machined part to its raw material batch, machining parameters, inspection results, and, where required, operator and machine identifiers. This is particularly important in regulated industries such as aerospace and medical devices.

Documentation typically includes material certificates, process records, inspection reports, and final conformity declarations aligned with applicable standards or customer-specific requirements.

Application-Specific Considerations

While the fundamental machining principles are consistent, each industry imposes distinct requirements on design, tolerances, and validation of titanium components.

Aerospace Components

Aerospace titanium parts include structural brackets, bulkheads, engine components, and landing gear elements. Key machining considerations involve:

Efficient removal of large volumes of material from forgings and billets; maintaining dimensional stability in thin-web and thin-wall sections; and ensuring repeatable accuracy across production batches.

Surface finish and structural integrity must support fatigue performance and corrosion resistance over long service periods. Holes for fasteners and joints demand precise location and tight tolerances to achieve correct load transfer within assemblies.

Medical Implants and Instruments

Medical titanium components cover orthopedic implants, dental fixtures, spinal cages, trauma plates, and surgical instruments. Machining must support the creation of intricate shapes, transitions, and functional surfaces.

Frequent requirements include smooth articulating surfaces, controlled roughness for bone ingrowth regions, and well-defined threads for secure anchoring. Cleanroom-compatible finishing, controlled burr removal, and validated cleaning protocols support regulatory compliance.

Industrial and Energy Sector Parts

Industrial titanium applications span chemical processing equipment, heat exchangers, offshore structures, and power generation components. Machining must handle varying part sizes, from small valve components to large plates and tube sheets.

Corrosion resistance and operational reliability are central. Machined surfaces often serve as sealing interfaces, coupling flanges, or rotating elements. Dimensional accuracy and surface finish must be consistent, particularly where titanium interfaces with dissimilar materials under pressure and temperature cycling.

Typical Issues in Titanium Machining and Engineering Responses

Engineering and process planning address several recurring issues associated with titanium machining to achieve reliable, cost-effective production without compromising quality.

Tool Wear and Process Stability

Tool wear in titanium machining tends to be concentrated at the cutting edge due to high temperatures and adhesion. Progressive wear changes the effective tool geometry and can lead to deviations in size and finish.

To maintain stability, machining programs incorporate tool life monitoring, adaptive feed control, and scheduled tool changes based on measured wear patterns rather than solely on time or part count. This approach helps keep tolerances within specified bands throughout production.

Part Distortion and Dimensional Drift

Residual stresses, heat input, and low stiffness can cause subtle dimensional changes during and after machining, especially in slender or thin-walled parts. Design and process measures include:

Use of stress-relieved stock; symmetric material removal; intermediate inspections between roughing and finishing operations; and precise control of clamping forces. In some cases, finishing passes are scheduled after controlled cooling to room-stable temperatures to minimize dimensional drift.

Burr Formation and Edge Quality

Burrs on edges and in small holes can interfere with assembly and, in medical applications, may be unacceptable for safety reasons. Machining parameters, tool geometry, and cutting direction are chosen to reduce burr height at the source.

Where required, secondary deburring processes are defined and validated to remove burrs while maintaining dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and traceability of the operations performed.