Titanium machining is a core process in aerospace, medical, automotive, energy, and high‑performance industrial applications. Titanium alloys combine high strength, low density, and excellent corrosion resistance, but they are also difficult to machine economically and reliably. This guide explains the main machining types, cost factors, cutting parameters, tooling choices, and best practices required to obtain precise, repeatable results with titanium parts.

Overview of Titanium and Its Machinability

Titanium is classified as a reactive, low thermal conductivity material. Compared with carbon and stainless steels, titanium conducts heat poorly and tends to keep heat in the cutting zone. This leads to high cutting temperatures and rapid tool wear if parameters and tooling are not optimized.

The two most commonly machined titanium categories are:

- Commercially Pure (CP) titanium (Grades 1–4) – lower strength, relatively better machinability.

- Alpha–beta alloys (e.g., Ti‑6Al‑4V / Grade 5, Ti‑6Al‑4V ELI / Grade 23) – high strength, widely used in aerospace and medical components, more demanding to machine.

Key machining characteristics of titanium alloys include:

- High strength at elevated temperature, increasing cutting forces and tool load.

- Low modulus of elasticity, leading to workpiece deflection and chatter if clamping is insufficient.

- Tendency to work‑harden and form built‑up edges on tools if cutting speed and lubrication are inadequate.

- Reactive surface, which may cause galling and adhesion to cutting tools at high temperatures.

Main Types of Titanium Machining

Titanium machining is performed using conventional subtractive processes adapted with specific strategies and tooling. The most widely applied include CNC milling, turning, drilling, tapping, and grinding.

CNC Milling of Titanium

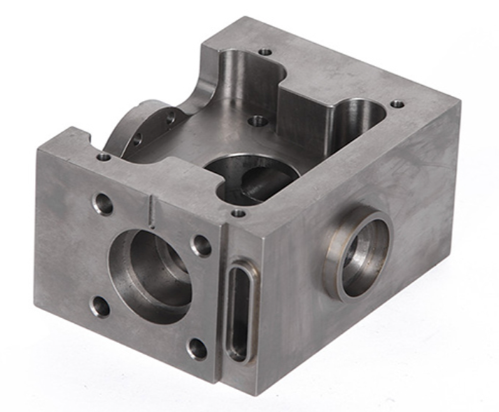

CNC milling is used for prismatic components, structural parts, housings, brackets, and complex 3D shapes. It is especially important for aerospace structural components and medical implants.

Typical methods applied in titanium milling:

- High‑efficiency roughing (trochoidal or adaptive toolpaths) to keep constant chip load and reduce radial engagement.

- Full‑slot or high‑axial depth machining with reduced radial width to control heat and tool load.

- Finishing with small depth of cut and optimized step‑over for dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

Ball‑nose and bull‑nose end mills are widely used for free‑form surfaces; square end mills are used for planar faces, pockets, and slots. Five‑axis machining is commonly used to maintain optimal tool orientation, reduce tool overhang, avoid collisions, and minimize tool deflection.

Turning of Titanium

Turning processes are used to produce shafts, rings, fasteners, and rotationally symmetric parts. Machinability during turning is influenced by chip control, rigidity, and thermal load on the cutting edge.

Common turning operations on titanium alloys include:

- External and internal rough turning with positive‑rake inserts and robust edge geometry.

- Finishing and profiling with sharp, high‑positive inserts to reduce cutting forces.

- Grooving and parting‑off using narrow inserts and careful feed control to manage chip evacuation.

Achieving consistent chip breakage is important. Long, stringy chips can wrap around the part, tool, or chuck, potentially damaging the workpiece or causing machine downtime. Appropriate chip‑breaker geometries and feed rates are essential to mitigate this.

Drilling, Boring, and Tapping Titanium

Drilling titanium requires attention to heat generation, chip evacuation, and tool wear. Poor drilling conditions can rapidly dull tools and lead to hole quality issues such as taper, bell‑mouthing, and burrs.

Key considerations:

Drilling: Use high‑quality carbide or cobalt drills with specialized geometries for titanium. Through‑coolant drills are preferred for deeper holes to maintain temperature control and evacuate chips effectively. Peck drilling is often needed, but the peck cycle should be optimized to minimize rubbing and heat buildup.

Boring: Boring bars used for titanium must be rigid, ideally with anti‑vibration design for deep bores. Finishing passes should be light with stable feed to maintain dimensional accuracy and surface finish.

Tapping: Thread cutting in titanium is sensitive to friction and torque. Form taps and cutting taps for titanium require high lubrication and reduced speeds. In many cases, thread milling with solid carbide tools is preferred, especially for high‑value parts or critical threaded features, because it reduces torque and provides better chip control.

Grinding and Finishing of Titanium

Grinding is used for tight tolerances and improved surface finish on titanium. Due to low thermal conductivity and chemical reactivity, titanium is susceptible to grinding burn and surface damage if parameters and coolant are not controlled.

Important aspects of grinding titanium:

- Use wheels with appropriate bond and abrasive (e.g., aluminum oxide, CBN for some applications).

- Maintain sharp abrasive grains to reduce rubbing and heat.

- Apply abundant coolant with proper delivery to the grinding zone.

Other finishing operations include honing, lapping, shot peening, and polishing, especially for surgical implants or sealing surfaces where low roughness and defect‑free surfaces are critical.

Material Grades and Their Influence on Machining

Different titanium grades have distinct mechanical and thermal properties, which directly affect machining behavior. Among them, Grade 5 (Ti‑6Al‑4V) is the most common structural alloy, while commercially pure grades are used where extreme strength is not required but corrosion resistance and biocompatibility are crucial.

| Grade / Alloy | Type | Approx. Yield Strength (MPa) | Relative Machinability (vs. low carbon steel = 100) | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 2 (CP Ti) | Commercially pure | ~345 | ~25–30 | Chemical processing, medical devices, marine components |

| Grade 4 (CP Ti) | Commercially pure (high strength) | ~550 | ~20–25 | Surgical implants, aerospace hardware |

| Grade 5 (Ti‑6Al‑4V) | Alpha‑beta alloy | ~880 | ~18–22 | Aerospace structures, engine parts, high‑performance components |

| Grade 23 (Ti‑6Al‑4V ELI) | Alpha‑beta alloy (ELI) | ~795 | ~18–22 | Implants, medical devices requiring high fracture toughness |

| Beta alloys (e.g., Ti‑10V‑2Fe‑3Al) | Metastable beta | 900–1100 | ~10–18 | High‑strength aerospace parts, landing gear components |

In general, commercially pure grades are somewhat easier to machine than high‑strength alpha‑beta or beta alloys, but all titanium materials require carefully controlled cutting conditions, sharp tooling, and effective coolant application.

Cost Structure of Titanium Machining

The cost of titanium machining depends on raw material, machining time, tool consumption, required tolerances, and quality control. Because titanium is expensive and difficult to cut, optimizing process parameters has a large impact on total part cost.

Calculate Your Titanium Machining Cost

Rough estimation for titanium machining (Ti-6Al-4V most common)

Material Cost and Stock Utilization

Titanium bar, billet, and plate have significantly higher price per kilogram than common steels or aluminum. In addition, titanium parts often start from oversize stock to allow fixturing and machining allowance, leading to higher buy‑to‑fly ratios (ratio of input material mass to finished part mass).

Typical cost‑relevant aspects:

- High raw material price, particularly for aerospace and medical‑grade alloys.

- Large amount of material removed in structural parts with pockets and ribs.

- Scrap management and traceability requirements for critical industries.

Reducing unnecessary stock, using near‑net‑shape forgings or additive preforms, and optimizing fixture design to allow minimal excess material can contribute significantly to cost reduction, even though the machining approach remains the same.

Machine Time and Labor

Due to conservative cutting speeds and feed rates, titanium machining often takes longer than machining aluminum or steel. Machine hourly rates for high‑performance CNC centers and skilled labor further elevate the cost.

Factors increasing machining time:

- Reduced cutting speeds to control heat and tool wear.

- Multiple semi‑finishing and finishing passes for tight tolerances.

- More complex toolpaths (e.g., adaptive roughing) to maintain chip load and extend tool life.

- Additional inspection and in‑process measurement for high‑value parts.

Tooling and Consumables

Titanium machining requires high‑quality tooling, coatings, and coolant systems. Tool cost per part can be substantial, especially for large production runs or difficult alloys.

Main contributors to tooling cost:

- Solid carbide and indexable tools with advanced coatings (e.g., TiAlN, AlTiN) specifically designed for titanium.

- Frequent tool changes to prevent catastrophic failure and protect expensive workpieces.

- Use of through‑coolant tools and high‑pressure coolant systems.

Balancing tool life against machining time is critical. Running tools too conservatively increases machine time, while aggressive cutting can cause unpredictable tool failure and scrap. Optimized parameters based on controlled testing can significantly improve cost efficiency.

Quality Control and Non‑Destructive Testing

Many titanium parts, especially in aerospace and medical applications, require rigorous quality control measures such as dimensional inspection, surface integrity evaluation, hardness checks, and non‑destructive testing (NDT). These steps add to the cost but are necessary to ensure fitness for service.

Common practices include:

- Coordinate measuring machine (CMM) inspection of critical dimensions.

- Surface roughness measurement with profilometers.

- Dye penetrant testing or other NDT for detecting surface flaws, depending on specification.

Key Cutting Parameters for Titanium Machining

The selection of cutting speed, feed, and depth of cut directly affects tool life, surface finish, and cycle time. Titanium machining generally uses lower cutting speeds, moderate feeds, and carefully controlled engagement.

| Operation | Tool Material | Cutting Speed vc (m/min) | Feed per Tooth / Rev | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rough Milling (Ti‑6Al‑4V) | Solid carbide end mill | 40–70 | 0.04–0.12 mm/tooth | Axial depth up to 2–3×D, radial engagement 5–20% of D, high‑pressure coolant recommended |

| Finish Milling (Ti‑6Al‑4V) | Solid carbide end mill | 60–90 | 0.02–0.06 mm/tooth | Shallow axial and radial cuts, focus on surface finish and dimensional accuracy |

| Rough Turning | Carbide insert | 40–80 | 0.15–0.35 mm/rev | Depth of cut 1–5 mm, use positive geometry and stable setup |

| Finish Turning | Carbide insert | 60–100 | 0.05–0.20 mm/rev | Depth of cut 0.2–1 mm, prioritize surface finish and chip control |

| Drilling (Ø < 10 mm) | Carbide drill | 20–50 | 0.05–0.15 mm/rev | Through‑coolant preferred, use optimized peck cycles for deeper holes |

| Tapping (cutting tap) | HSS‑E / carbide | 5–15 | Refer to tap pitch | Abundant lubrication, reduced speed compared with drilling |

These values are indicative starting points. Optimal parameters depend on machine rigidity, tool design, coolant system, titanium grade, and required part quality. Process verification through controlled trials is recommended whenever a new combination of material, tool, and machine is introduced.

Tooling Strategies and Tool Material Selection

Proper tooling is essential for reliable titanium machining. Tool geometry, substrate, and coating all influence heat management, chip formation, and tool wear.

Tool Material and Coatings

Solid carbide tools are widely used for milling and drilling titanium due to their hardness and hot‑strength. Advanced coatings improve wear resistance and reduce friction.

Common combinations:

- Micro‑grain carbide with TiAlN or AlTiN coatings for general titanium milling and drilling.

- Uncoated or specially coated carbide where built‑up edge is a concern or where coating delamination would be problematic.

- CBN and ceramics for some finishing and continuous turning operations, where conditions are very stable and heat can be localized in the chip.

High‑speed steel (HSS‑E) tools are still used for taps and some drills, especially for small diameters and when machine rigidity is limited, but tool life may be shorter compared with carbide.

Geometry Considerations

Tool geometry should promote sharp cutting, low friction, and stable chip formation. Typical characteristics include:

- Positive rake angles to reduce cutting forces and heat generation.

- Optimized clearance angles to reduce rubbing against the workpiece.

- Polished flutes and chip‑breaker designs to improve chip evacuation and reduce built‑up edge.

- Corner radii or chamfers on inserts and end mills to strengthen the cutting edge.

For milling, multi‑flute tools are used, but flute count must be balanced with chip space. Too many flutes reduce chip space and increase risk of clogging, especially in deep pockets or when chip evacuation is difficult.

Tool Holding and Runout Control

Accurate and rigid tool holding is critical for titanium machining. Excessive runout leads to uneven tooth loading, increased vibration, and poor surface finish.

Common tool holding systems include:

- Shrink‑fit holders for high‑speed, high‑precision milling.

- Hydraulic chucks for excellent runout and vibration damping, especially for finishing.

- Collet chucks for general‑purpose applications, with particular attention to cleanliness and clamping torque.

Minimizing tool overhang reduces deflection and improves tool life. When long reach is necessary, specialized anti‑vibration holders can be used to suppress chatter.

Coolant and Lubrication Practices

Because titanium retains heat in the cutting zone, coolant strategy is a central factor in successful machining. High cutting temperatures can cause rapid tool wear, workpiece surface damage, and dimensional instability.

Coolant Type and Delivery

Water‑miscible cutting fluids with appropriate additives are widely used for titanium machining. Neat oils may be used in specific finishing operations or where maximum lubrication is required, but they can limit cutting speed and generate more heat.

Important considerations:

- High‑pressure coolant (HPC) directed precisely at the cutting edge, particularly in deep pockets and drilling operations.

- Through‑tool coolant channels in drills and end mills for efficient chip evacuation.

- Clean, filtered coolant to avoid nozzle blockage and maintain flow consistency.

Consistent coolant delivery helps prevent localized overheating and maintains dimensional stability, especially on thin‑walled titanium components.

Minimum Quantity Lubrication (MQL) and Dry Cutting

MQL and dry cutting are less common for titanium due to high heat generation and the need for temperature control, but they are used in some dedicated processes with optimized tools and parameters. When applied, careful testing is required to ensure tool life and surface integrity meet specifications.

Workholding, Stability, and Vibration Control

Workholding has a significant influence on dimensional accuracy and surface quality in titanium machining. Due to the material’s low modulus of elasticity, thin features and walls are prone to deflection and vibration.

Rigid Fixturing

Reliable fixtures with good support close to the cutting zone are essential. Considerations include:

- Using robust clamping methods that avoid local distortion.

- Supporting thin walls or ribs with sacrificial supports or fill material where permitted.

- Minimizing unsupported overhangs and cantilevers in the workpiece.

Modular fixturing systems can be configured to provide multiple support points while allowing chip evacuation. Vacuum fixtures can be used for plate‑like parts but must be carefully designed to maintain grip under cutting loads.

Vibration and Chatter Reduction

To control chatter in titanium machining:

- Reduce tool overhang and use anti‑vibration tool holders where necessary.

- Adjust spindle speed to move away from resonant frequencies (spindle speed tuning).

- Use appropriate feed per tooth to maintain positive cutting pressure and avoid rubbing.

- Adopt step‑down strategies that balance radial and axial engagement to avoid intermittent cutting.

Machine structure and spindle condition also play a major role. A rigid, well‑maintained machine tool allows more aggressive yet stable cutting parameters, ultimately improving productivity and cost efficiency.

Surface Finish, Tolerances, and Dimensional Control

Titanium parts often have stringent tolerances and surface finish requirements. Achieving these consistently requires an integrated approach covering toolpath planning, finishing strategies, and inspection.

Surface Roughness Requirements

Typical surface roughness targets for titanium machining include:

- Ra 1.6–3.2 µm for general structural features after finishing.

- Ra 0.4–0.8 µm for sealing surfaces, bearing seats, and many medical components.

- Ra < 0.4 µm for highly polished or tribologically critical surfaces, often achieved through grinding or polishing after machining.

Finishing passes are usually executed at reduced feed and depth of cut with sharp tools. Toolpath direction and overlap are controlled to avoid marks and cusps exceeding allowed roughness. Where surface integrity is critical, additional processes such as superfinishing, lapping, or electropolishing may be applied.

Tolerances and Geometric Accuracy

Typical dimensional tolerances in titanium machining range from ±0.05 mm for non‑critical features to ±0.005 mm or tighter for precision fits. Achieving consistently tight tolerances requires:

- Compensation for thermal effects during machining, especially for long, slender components.

- In‑process measurement (probing) and tool wear compensation to maintain dimensions over long runs.

- Stable clamping and minimal part deformation during machining and unclamping.

Geometric tolerances such as flatness, roundness, cylindricity, and position are controlled through process planning, appropriate machining sequences, and selection of reference surfaces.

Typical Issues in Titanium Machining

In practical environments, titanium machining presents recurring issues that affect quality and cost. Understanding these pain points helps to structure improvement actions.

Excessive Tool Wear and Breakage

High temperatures and mechanical load at the cutting edge can lead to rapid flank wear, crater wear, and chipping. Uncontrolled tool wear increases the risk of dimensional drift and sudden breakage. Key preventive measures include correct cutting data, optimized coolant delivery, periodic tool inspection, and replacement before catastrophic failure.

Chatter and Surface Defects

Vibration can create chatter marks, dimensional inaccuracies, and accelerated tool wear. Incorrect combination of tool overhang, cutting data, and clamping rigidity often leads to this problem. Adapting the machining strategy, reinforcing fixturing, and tuning spindle speeds are practical countermeasures.

Chip Control and Heat Management

Long, continuous chips and poor chip evacuation hinder automated machining and can damage surfaces. Adequate chip‑breaker design, feed control, and high‑pressure coolant are necessary to maintain continuous production and avoid machine stoppages for manual chip removal.

Best Practices for Cost‑Effective Titanium Machining

Cost‑effective titanium machining is achieved by combining proper planning, optimized cutting parameters, suitable tooling, and robust process control. The following best practices are commonly adopted to improve both quality and economics.

Process Planning and Sequence Optimization

Effective process planning includes:

- Defining the machining sequence so that the most rigid state of the workpiece is used for roughing, and final finishing is done after most material removal is complete.

- Allocating enough machining allowance on critical surfaces to correct distortion from earlier operations.

- Using intermediate stress‑relief heat treatments where specifications allow, particularly for parts with large material removal or complex geometries.

Parameter Optimization and Tool Life Management

Testing and optimizing cutting conditions can significantly reduce costs. Approaches include:

- Conduct initial parameter trials on representative samples before full‑scale production.

- Monitor tool wear visually or with tool life management systems and adjust tool change intervals accordingly.

- Use standardized parameter sets for specific combinations of material, tool, and machine to simplify programming and reduce variability.

Monitoring and Quality Assurance

In‑process monitoring and final inspection help maintain quality and avoid scrap:

- Tool load monitoring systems can detect unusual cutting forces that indicate tool wear, chipping, or improper engagement.

- Spindle and vibration monitoring helps identify chatter and potential machine issues.

- Dimensional checks with on‑machine probes reduce handling and improve repeatability for complex parts.

For critical applications, controlled documentation of process parameters, tooling, and inspection results provides traceability and supports continuous improvement.

Applications of Titanium Machining

Titanium machining is essential in industries where strength‑to‑weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility are key requirements.

Aerospace and Defense

Titanium components are used in airframes, landing gear, engine parts, fasteners, and structural brackets. Machining strategies must meet strict requirements for fatigue resistance, surface integrity, and dimensional accuracy. Multiple operations on complex 5‑axis machines are common, and cycle times can be long due to high material removal volumes and tight tolerances.

Medical and Dental Devices

Titanium’s biocompatibility makes it the material of choice for implants, prosthetics, surgical instruments, and dental components. Machining must provide smooth surfaces and accurate geometries to ensure proper fit and minimize surface defects that could affect tissue interaction. Polishing, passivation, and thorough cleaning are often required after machining.

Automotive, Energy, and Industrial Applications

In high‑performance automotive systems, titanium is used for connecting rods, valves, and exhaust system components. In the energy sector, titanium is applied in heat exchangers, offshore structures, and chemical processing equipment where corrosion resistance is critical. Machining strategies are adapted to each application’s requirements, balancing cost, performance, and production volume.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What makes titanium difficult to machine compared to other metals?

Titanium has low thermal conductivity, high strength, and strong chemical reactivity, which leads to heat concentration at the cutting edge, rapid tool wear, and risk of galling.

What are the most common types of titanium used in machining?

Commercially pure titanium (Grades 1–4) and titanium alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V (Grade 5) are the most commonly machined grades.

How much does titanium machining typically cost?

Titanium machining costs are higher than aluminum or steel due to material price, tool wear, slower cutting speeds, and specialized machining requirements.

What are best practices for reducing tool wear in titanium machining?

Maintaining consistent chip load, avoiding dwell time, using sharp tools, and applying adequate cooling are critical best practices.