Selecting the right material for machining is a critical engineering decision that affects manufacturability, cost, performance, and lifecycle reliability. Aluminum, steel, and engineering plastics are among the most widely used materials in CNC and conventional machining. Each has distinct mechanical, thermal, and economic characteristics that make it more or less suitable for a given application.

This guide compares aluminum, steel, and plastic from a machining perspective and provides a systematic framework for choosing the best option for your parts.

Key Factors in Machining Material Selection

Before comparing specific materials, it is essential to understand the main criteria that drive material selection for machined parts. In practice, engineers typically balance several factors rather than optimizing for only one.

- Mechanical performance: strength, stiffness, hardness, wear resistance, fatigue.

- Machinability: cutting forces, chip formation, tool wear, achievable surface finish.

- Dimensional requirements: tolerances, stability, distortion control, flatness.

- Thermal behavior: heat resistance, thermal expansion, thermal conductivity.

- Environmental and chemical resistance: corrosion, moisture, UV, chemicals.

- Weight: density and its effect on mass, inertia, and ergonomics.

- Cost: raw material price, machining time, tooling cost, finishing operations.

- Regulations and industry standards: certifications and compliance.

In many projects, trade-offs arise between these aspects. For example, maximizing strength may increase machining difficulty or cost. A structured comparison of aluminum, steel, and plastics helps choose a balanced solution.

Overview of Aluminum, Steel, and Plastic for Machining

The table below summarizes key characteristics of commonly machined aluminum alloys, steels, and engineering plastics used for precision components.

| Property (typical ranges) | Aluminum Alloys | Steels (carbon & alloy) | Engineering Plastics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ~2.7 | ~7.7–8.0 | ~1.0–1.4 |

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | ~130–570 | ~400–2000 (heat-treated) | ~40–170 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | ~68–75 | ~190–210 | ~1–4 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) | ~120–200 | ~15–60 | ~0.2–0.4 |

| Melting / softening | ~580–660 °C | ~1370–1510 °C | Softens from ~80–260 °C (glass transition or melting) |

| Relative machinability | Excellent | From moderate to very good (depends on grade and hardness) | Good but sensitive to heat and deflection |

| Corrosion resistance | Good (improved with anodizing) | Low for plain carbon (needs protection); high for stainless | Often excellent against moisture and many chemicals |

| Material cost (per kg) | Moderate | Low to moderate | Low to high (depends on polymer type) |

| Typical use cases | Lightweight structures, housings, heat-dissipating parts | Load-bearing, wear-resistant, high-temperature parts | Insulating, low-friction, chemical-resistant components |

Aluminum as a Machining Material

Aluminum alloys are widely used in CNC machining due to their high machinability, good strength-to-weight ratio, and excellent thermal conductivity. They are especially common in aerospace, automotive, electronics, and general industrial applications.

Common Machined Aluminum Alloys

The following wrought alloys are frequently used in machined parts:

- 6061-T6: general-purpose alloy with good strength, excellent machinability, and weldability.

- 6082-T6: similar to 6061 but often favored in structural applications.

- 7075-T6/T651: high-strength alloy for critical, lightweight components.

- 2024-T351: high strength and fatigue resistance, used in aerospace structures.

Typical property ranges for commonly machined aluminum alloys:

Density: approximately 2.7 g/cm³.

Ultimate tensile strength (UTS): about 130–570 MPa depending on alloy and temper (e.g., 6061-T6 ~290 MPa, 7075-T6 ~570 MPa).

Yield strength: roughly 70–500 MPa.

Elastic modulus: ~68–75 GPa.

Hardness (Brinell): typically ~60–150 HBW.

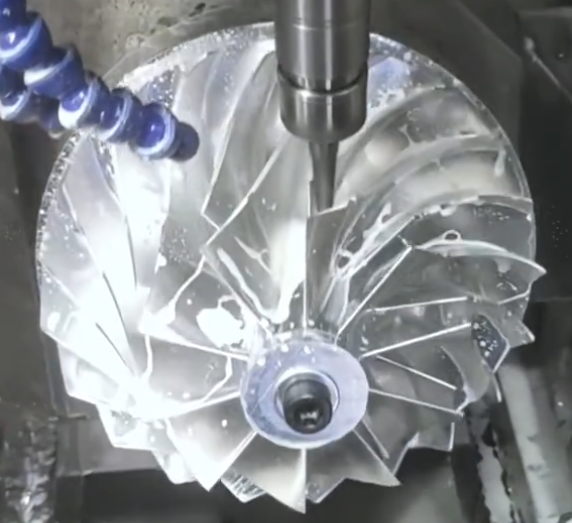

Machinability Characteristics of Aluminum

Aluminum is considered easy to machine, but its behavior depends on the specific alloy and temper.

Key machining characteristics:

- Low cutting forces: reduces machine load and allows higher feed and speed.

- High cutting speeds: surface cutting speeds can exceed 500 m/min with appropriate tools and cooling.

- Tool materials: carbide tools are common; high-speed steel can be used for lower production volumes.

- Chip formation: short, discontinuous chips in many alloys; some grades may produce longer chips requiring chip breakers.

- Built-up edge risk: aluminum tends to adhere to cutting tools, especially at lower cutting speeds or with inadequate lubrication.

Recommended practices include sharp tools, polished flutes, appropriate rake angles, and effective cutting fluids or mist to minimize sticking and improve surface finish.

Dimensional Stability and Tolerances in Aluminum Parts

Aluminum parts can hold tight tolerances when machined with stable setups and controlled temperatures. However, some aspects require attention:

- Thermal expansion: coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) is around 22–24 × 10⁻⁶ /K, higher than steel. Dimensional changes from temperature variation are more significant.

- Residual stresses: large plates or thick sections can warp when heavily machined if internal stresses are not relieved.

- Thin walls: low stiffness compared with steel increases the tendency for deflection and chatter during machining of thin sections.

For high-precision aluminum parts, stress-relieved stock (e.g., 6061-T651) and symmetric material removal strategies help improve dimensional stability.

Surface Finish and Post-Processing for Aluminum

Aluminum typically yields good surface finishes directly from machining, especially with sharp tools and fine feed rates. Average roughness (Ra) values below 0.8 µm are common with standard finishing passes, and finer finishes are achievable with optimized parameters.

Common post-machining processes include:

- Anodizing: enhances corrosion resistance, wears resistance, and allows coloring. Thickness often ranges from about 5 µm (decorative) to 25 µm or more (hard anodizing).

- Conversion coatings: chemical films that improve paint adhesion and corrosion resistance.

- Polishing and bead blasting: to adjust cosmetic appearance and surface texture.

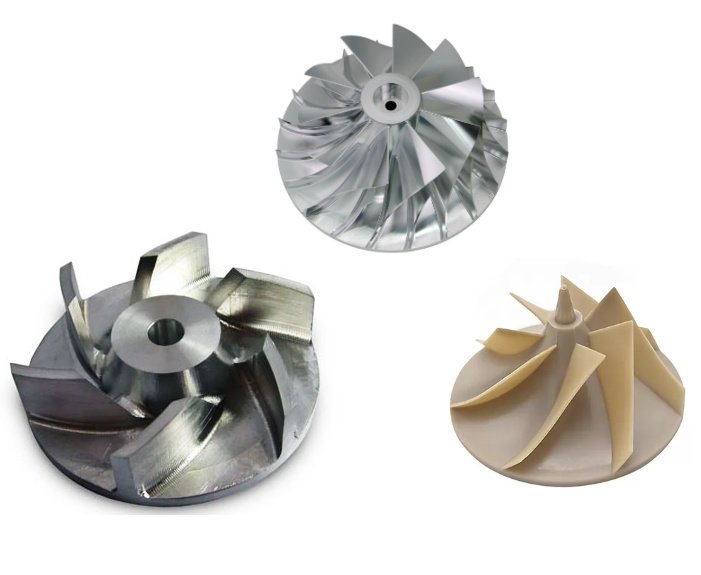

Typical Applications and Use Cases for Aluminum

Aluminum is often chosen when a combination of moderate to high strength, low weight, and good machinability is required. Typical machined products include:

- Structural brackets, frames, and mounts in aerospace and robotics.

- Housings and enclosures for electronics and instrumentation.

- Heat sinks and thermal management components in power electronics.

- Fixtures, jigs, and prototype mechanical parts.

Where higher strength is needed without greatly increasing weight, 7xxx and 2xxx series alloys are preferred despite slightly more challenging machinability and sometimes lower corrosion resistance compared with 6xxx alloys.

Steel as a Machining Material

Steel offers superior strength, stiffness, and wear resistance compared with aluminum and most plastics. It is used for heavily loaded components, safety-critical parts, and high-temperature environments. Steels span a wide range of compositions and heat treatments, which significantly influence machinability.

Common Machined Steel Grades

Steels can be broadly categorized as carbon steels, alloy steels, and stainless steels. Frequently machined grades include:

- Low-carbon steels: e.g., 1018, 1020, 1045 for general mechanical parts and shafts.

- Free-machining steels: e.g., 12L14, 11L41 containing additives (such as lead or sulfur) to improve chip breaking and reduce tool wear.

- Alloy steels: e.g., 4140, 4340 for higher strength and toughness requirements.

- Stainless steels: e.g., 303, 304, 316 (austenitic), 410, 420 (martensitic) for corrosion resistance.

- Tool steels: e.g., D2, O1, H13 for tooling, dies, and wear-resistant parts.

Typical property ranges (depending on grade and heat treatment):

Density: about 7.7–8.0 g/cm³.

Ultimate tensile strength: ~400–2000 MPa.

Yield strength: ~250–1800 MPa.

Elastic modulus: ~190–210 GPa.

Hardness: from ~120 HBW for annealed mild steels to above 60 HRC for fully hardened tool steels.

Machinability of Carbon and Alloy Steels

Machinability of steels varies widely. Factors such as carbon content, alloying elements, microstructure, and hardness strongly influence cutting behavior.

Key points for carbon and alloy steels:

- Cutting forces: significantly higher than aluminum due to higher strength and hardness.

- Machining speeds: lower surface cutting speeds are used to control tool wear and heat, commonly in the range of 80–250 m/min for carbide tools, depending on hardness.

- Chip control: steels generally produce well-defined chips; free-machining grades generate short, segmented chips that improve process reliability.

- Tool wear: abrasion, adhesion, and diffusion wear are common; proper tool selection and cooling are essential.

Pre-hardened steels (e.g., 4140 pre-hardened to ~28–32 HRC) offer a balance between strength and machinability, allowing machining without subsequent hardening for many applications.

Machining Stainless Steels

Stainless steels are selected for corrosion resistance, yet they can be more challenging to machine. Common issues include work hardening and poor thermal conductivity.

Typical characteristics:

- Work hardening tendency: austenitic grades (e.g., 304, 316) can harden rapidly in the cutting zone if feeds are too light or tools rub instead of cutting.

- Lower thermal conductivity: heat accumulates near the cutting edge, accelerating tool wear.

- Built-up edge: can occur if cutting parameters and tool geometries are not optimized.

- Machinability rating: some free-machining stainless steels (such as 303) include sulfur or other additives to improve chip control and reduce tool wear, at the cost of slightly lower corrosion resistance in some environments.

Effective machining of stainless steels typically requires high-quality carbide tools, rigid setups, adequate coolant flow, and sufficiently high feed rates to minimize rubbing.

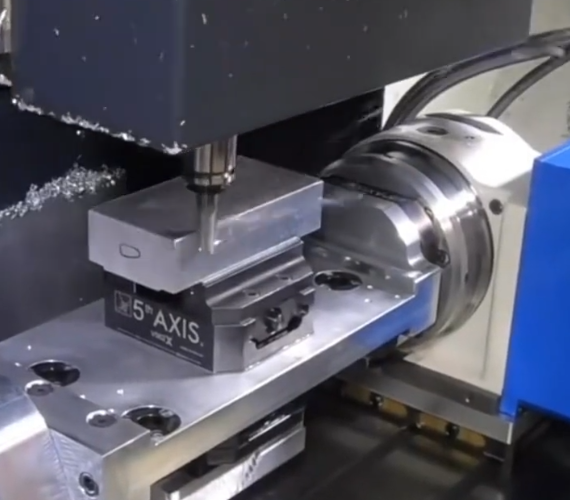

Dimensional Stability, Heat Treatment, and Distortion in Steel

Steel components often undergo heat treatment to achieve required hardness and mechanical properties. However, heat treatment can introduce or relieve stresses and cause dimensional changes.

Important considerations:

- Heat treatment sequence: many designs require rough machining, heat treatment, and finish machining to final dimensions.

- Distortion: quenching and phase transformations may induce warping, especially in asymmetrical or thin-walled parts.

- Stress relief: low-temperature stress-relief cycles can reduce internal stresses after rough machining.

- Stability during machining: higher stiffness of steel compared with aluminum or plastics helps minimize deflection, supporting tight tolerances on small or slender features when fixtures are well designed.

Careful process planning, including allowance for material removal after heat treatment, is often needed for high-precision steel components.

Surface Finish and Post-Processing for Steel

Machined steels can achieve a wide range of surface finishes. Typical Ra values after standard finishing passes range from ~0.8–3.2 µm, depending on conditions and tool geometry. Finer finishes require lower feed rates, optimized tool nose radius, and stable setups.

Common post-processing operations include:

- Heat treatment: quenching, tempering, case hardening, nitriding, or induction hardening.

- Grinding: to achieve tight tolerances and fine finishes, particularly on hardened parts.

- Surface coatings: plating (zinc, nickel, chrome), black oxide, or specialized coatings for wear, corrosion protection, or aesthetics.

- Passivation (stainless steels): removes free iron and improves corrosion resistance.

Typical Applications and Use Cases for Steel

Steel is chosen where high load capacity, wear resistance, and durability are essential. Typical machined steel parts include:

- Shafts, gears, and bearings in mechanical drives.

- Molds, dies, and tooling components.

- Structural elements subjected to high stress or impact.

- Fasteners, safety-critical components, and pressure-containing parts.

For frequently sliding or heavily loaded components, hardened or surface-treated steel is often the default choice due to its combination of strength and wear resistance.

Plastics as Machining Materials

Engineering plastics offer low weight, electrical insulation, chemical resistance, and low friction. While many plastics are processed by molding or extrusion, machining is widely used for low-volume production, prototypes, and complex geometries that are difficult to mold.

Common Machined Engineering Plastics

Several families of thermoplastics and thermosets are used for machined parts. Common examples include:

- Acetal (POM): good dimensional stability, low friction, and moderate strength.

- Nylon (PA): good toughness and wear resistance, some moisture absorption.

- Polycarbonate (PC): impact-resistant, transparent, moderate strength.

- Polyetheretherketone (PEEK): high strength, excellent chemical resistance, and high temperature capability.

- Polyethylene (PE): low friction, good chemical resistance, lower stiffness.

- PTFE: very low friction and excellent chemical resistance, low stiffness and creep resistance.

- GFR (glass fiber reinforced) plastics: improved stiffness and strength compared with unfilled grades.

Typical property ranges for engineering plastics:

Density: about 1.0–1.4 g/cm³ (some reinforced grades higher).

Ultimate tensile strength: ~40–170 MPa.

Elastic modulus: roughly 1–4 GPa (unfilled), higher for reinforced grades.

Continuous use temperature: approximately 80–260 °C depending on polymer.

Machinability Characteristics of Plastics

Most plastics are easy to cut but require parameter adjustments compared with metals due to low stiffness, low melting temperature, and different chip behavior.

Typical machining characteristics:

- Low cutting forces: tool loads are much lower than for metals.

- Heat sensitivity: excessive heat can cause softening, melting, or surface damage. Cutting speeds are often moderate, and sharp tools with positive rake angles are preferred.

- Chip formation: some plastics (e.g., nylon, PE) produce long, continuous chips; effective chip evacuation and chip breaking are necessary to avoid entanglement.

- Tool materials: carbide tools are widely used; for some operations, high-speed steel can also be suitable due to lower cutting temperatures.

Coolant usage may be reduced or omitted for some plastics, but air blast or minimal lubrication helps with chip removal and temperature control. Many plastics respond well to sharp tools with honed edges to prevent tearing.

Dimensional Stability, Creep, and Moisture Effects

Dimensional control in plastics is more complex than in metals due to higher thermal expansion, creep, and moisture absorption in some polymers.

Key considerations include:

- Thermal expansion: CTE is typically in the range of ~50–150 × 10⁻⁶ /K or higher, several times that of steel. Tolerances must account for expected temperature variation.

- Creep and relaxation: under constant load over time, plastics can deform gradually, especially near their service temperature limit. Tight fits and load-bearing dimensions need conservative design.

- Moisture absorption: materials like nylon absorb water and change dimensions. Pre-conditioning the material and controlling humidity may be necessary for high-precision parts.

- Internal stresses: uneven cooling in semi-finished plastic stock can cause warping during machining or later in service.

To improve stability, it is common to rough-machine plastic parts, allow them to relax or condition, and then perform a finish machining step.

Surface Finish and Post-Processing for Plastics

Plastics can achieve very smooth finishes if machined with sharp tools and low feed rates. However, surface tearing or smearing can occur if tools are dull or cutting temperatures are too high.

Post-processing options include:

- Polishing: especially for transparent plastics such as polycarbonate or acrylic to restore clarity.

- Flame or vapor polishing: used for certain clear plastics to improve optical quality.

- Annealing: some plastics may be annealed to relieve residual stresses and improve dimensional stability.

Surface roughness targets must be compatible with the plastic type and its intended function. For example, sealing surfaces or bearing surfaces may require specific roughness ranges to control friction and wear.

Typical Applications and Use Cases for Plastics

Engineering plastics are used where low weight, corrosion resistance, electrical insulation, or low friction are more important than maximum strength.

- Bushings, sliding guides, and wear strips.

- Insulating components in electrical and electronic devices.

- Fluid handling components in chemical environments.

- Prototypes and functional mock-ups where tooling for molding is not justified.

Reinforced plastics, such as glass fiber reinforced PEEK, are used in demanding environments where moderate to high strength and chemical resistance are required, including some aerospace and medical devices.

Comparative Analysis: Aluminum vs Steel vs Plastic

Choosing among aluminum, steel, and plastic requires matching material capabilities to the design and manufacturing requirements of the part. The table below summarizes comparative aspects relevant to machinists and design engineers.

| Criterion | Aluminum | Steel | Plastics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strength and load capacity | Moderate to high | High to very high | Low to moderate |

| Stiffness | Medium | High | Low (higher for reinforced grades) |

| Weight (for same volume) | Low | High | Very low |

| Machining speed | High | Medium | Medium (limited by heat) |

| Tool wear | Low to moderate | Moderate to high | Low (some filled grades can be abrasive) |

| Dimensional stability | Good with proper stress relief | Very good; may require stress relief and controlled heat treatment | Moderate; affected by temperature, creep, and moisture |

| Corrosion and chemical resistance | Good to very good (with coatings) | Low for plain steels; high for stainless and coated steels | Often excellent, depending on polymer and chemical |

| Thermal resistance | Moderate (softens above ~150–200 °C) | High (retains strength at elevated temperatures) | Varies widely; many limited below ~120 °C, high-performance plastics up to ~260 °C |

| Cost of machined part | Often moderate; high cutting speeds reduce machining time | Moderate; longer machining times, additional heat treatment or coatings may add cost | Variable; material cost may be higher per kg, but shorter cycle times and lower weight can offset |

| Typical precision | Tight tolerances achievable with controlled process | Very tight tolerances achievable, grinding often used for finishing | Tight tolerances possible but require allowance for thermal and moisture effects |

Application-Driven Material Selection

Material choice should be driven by the application requirements. The following subsections outline typical scenarios and appropriate material decisions.

High-Strength Structural Components

For parts subject to significant mechanical loads, impact, or fatigue, steel is usually the primary candidate due to its high strength and stiffness. Alloy steels with appropriate heat treatments provide the highest safety margins.

Aluminum can be used when weight reduction is essential and loads are compatible with the selected alloy’s strength. 7xxx and 2xxx series aluminum alloys, while more demanding to machine than 6xxx series, deliver significantly higher strength and are common in aerospace structures.

Plastics are generally limited to moderate loads or applications where deformation is acceptable. Reinforced plastics extend the range but do not reach the stiffness and strength of steel.

Lightweight Components and Moving Assemblies

When minimizing mass and inertia is important, aluminum and plastics are preferred. Aluminum provides a compromise between strength and mass, suitable for moving frames, robotic arms, and drone structures.

Plastics may be chosen for small, low-load moving parts such as cams, levers, or sliding guides, especially where low friction and noise reduction are desired.

Corrosion Resistance and Harsh Environments

In corrosive or chemically aggressive environments, material selection focuses on compatibility with the media.

- Stainless steels (such as 316) are used for marine, chemical, and food processing applications where both strength and corrosion resistance are needed.

- Aluminum with appropriate coatings (such as anodizing) is suitable for many outdoor and industrial environments.

- Plastics such as PTFE, PVDF, or PEEK are used in highly aggressive chemical environments where metals may rapidly corrode.

When combining mechanical load and extreme chemical exposure, high-performance plastics or specific stainless steel grades are often required.

Thermal Management and Heat Dissipation

For components that must dissipate heat efficiently, such as heat sinks, housings for power electronics, or thermal interface structures, aluminum’s high thermal conductivity and machinability make it a primary choice.

Steel has lower thermal conductivity and is less effective for heat dissipation, though its high temperature strength makes it suitable where structural integrity at elevated temperatures is more important than heat transfer.

Plastics generally act as thermal insulators and are chosen when electrical and thermal insulation is needed rather than heat conduction.

Electrical and Magnetic Considerations

Material selection can also be influenced by electrical conductivity and magnetic behavior.

- Aluminum: good electrical conductor, non-magnetic; suitable for lightweight conductive components and enclosures where electromagnetic properties are considered.

- Steel: usually magnetic (except some austenitic stainless steels), electrically conductive; used in magnetic circuits and applications where magnetic properties are functional requirements.

- Plastics: electrical insulators and non-magnetic; ideal for insulating components, connectors, and parts near sensitive electronics.

In high-frequency applications, material conductivity and magnetic properties can affect heating and signal behavior, which must be considered during material selection.

Precision, Tolerances, and Surface Quality Requirements

For parts with very tight tolerances and demanding surface quality, both aluminum and steel are well suited. Steel’s higher stiffness allows better control of deflection for thin, high-aspect-ratio features, while aluminum allows fast material removal and stable cutting at high speeds.

Plastics can also meet tight tolerances, but designers must account for dimensional changes due to temperature, moisture, and long-term creep. Tolerances that are easily achievable in steel may require additional process control and environmental management when parts are machined from plastics.

Cost Considerations for Machining Materials

Cost analysis should consider more than just raw material price. The total cost of a machined part includes material, machining time, tooling, finishing, and any heat treatment or post-processing.

Raw Material and Stock Availability

Steel and aluminum are widely available in diverse stock forms: bar, plate, tube, and profile. This supports efficient material utilization and reduced waste. Commodity grades of steel often have lower cost per kilogram than aluminum, but the higher density means part weight is greater for the same volume.

Engineering plastics may have higher cost per kilogram, especially for high-performance grades like PEEK. However, for small or low-volume parts, material cost can be minor compared with machining time and setup.

Machining Time and Productivity

Aluminum’s high machinability and ability to run at high cutting speeds often reduce machining time and labor cost. For large production batches where machine time is a major cost driver, aluminum may be more economical than steel even if raw material cost per kilogram is higher.

Steel machining typically requires lower speeds and may involve multiple operations such as roughing, semi-finishing, heat treatment, and finishing (for example, grinding). These steps add time and cost but may be necessary to achieve required properties.

Plastics generally allow high feed rates and low cutting forces, yet their sensitivity to heat and deformation requires careful parameter control. For complex parts, the need for multi-stage machining to manage warping or stress relaxation can influence cost.

Tooling and Maintenance

Tool wear is strongly influenced by the material’s hardness and abrasiveness. Steels, especially hardened or alloy grades, consume more tooling and require frequent replacement or regrinding. Free-machining steels reduce tool wear but may not meet all performance requirements.

Aluminum causes low to moderate tool wear and typically extends tool life. The primary issue is built-up edge, which can be mitigated with appropriate tool coatings and cutting conditions.

Plastics cause minimal tool wear in unfilled grades, but glass-filled or mineral-filled plastics can be abrasive, requiring tools with wear-resistant coatings and possibly shorter tool life than expected for unfilled polymers.

Design and Machining Pain Points

Several recurring difficulties appear when machining or designing parts in aluminum, steel, or plastics. Addressing these early in the design phase can reduce manufacturing risks.

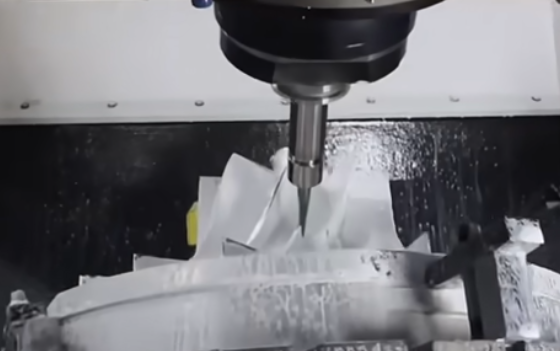

Thin-Walled and Complex Geometry Parts

Thin-walled components, deep pockets, and long, slender features are susceptible to deflection, chatter, and dimensional inaccuracies. While steel’s higher stiffness helps, complex shapes in aluminum or plastics may require specialized setups, fixtures, and machining strategies.

Practical approaches include:

- Using intermediate support ribs during machining that are removed in a final pass.

- Optimizing cutting parameters to reduce cutting forces and vibration.

- Employing multiple light passes rather than aggressive roughing for fragile features.

Residual Stresses and Warping

Residual stresses in rolled or extruded stock can cause parts to warp as material is removed. This is especially visible when machining large plates or long bars.

Mitigation options include:

- Using stress-relieved stock (for example, T651 aluminum plate or normalized steel).

- Symmetrical material removal to maintain balance in the part.

- Roughing the part, allowing it to stabilize, and then performing a finish pass.

Surface Finish Requirements and Secondary Operations

Very low roughness or specific textures may require additional operations such as grinding, polishing, or coating. Each step adds cost and potential dimensional change.

During design, it is important to specify surface finish only where functionally necessary and to understand the achievable finishes directly from machining for aluminum, steel, and plastics.

Guidelines for Selecting Between Aluminum, Steel, and Plastic

A structured material selection process helps align design, performance, and manufacturing requirements. The following guidelines provide a practical decision framework.

1) Define Functional Requirements

Begin by quantifying requirements such as:

- Load conditions (static, dynamic, fatigue).

- Operating temperature range.

- Required lifespan and safety factors.

- Environmental conditions (corrosion, chemicals, humidity, UV exposure).

- Electrical and magnetic properties.

These define a minimum set of material properties for candidate materials.

2) Assess Geometric and Tolerance Constraints

Consider part geometry, tolerances, wall thicknesses, and feature sizes. For extremely tight tolerances or high-aspect-ratio features:

- Steel provides a stiffness advantage and may simplify achieving dimensional targets.

- Aluminum allows high productivity but may need thicker walls or design reinforcement in certain regions.

- Plastics require careful tolerance specification and environment control, especially for long-term stability.

3) Estimate Lifecycle and Manufacturing Cost

Compare total cost including material, machining time, tooling, heat treatment, surface finishing, and expected scrap rates. In some cases, aluminum yields lower cost due to fast machining; in others, steel is more economical due to lower material cost and higher durability.

For small, low-load components, plastics may offer the most cost-effective solution, especially where machining time is short and no post-processing is needed.

4) Verify Compliance with Standards and Industry Practices

Some industries have established material preferences or requirements. For instance, pressure vessels, safety-related automotive parts, or certain aerospace components may be required to use specific steel or aluminum grades. In electrical or medical devices, particular plastics or stainless steels may be preferred for regulatory or cleanliness reasons.

5) Prototype and Evaluate Critical Parts

For critical applications, building prototypes in more than one material and evaluating performance under realistic conditions can reveal hidden issues such as unexpected deformation, wear, or thermal behavior.