Some metals are inherently difficult to CNC machine because of their strength, hardness, toughness, work hardening, or thermal properties. Understanding how and why these metals are hard to machine is essential for selecting the right cutting tools, parameters, and process strategy to achieve precision, acceptable tool life, and economic productivity.

Key Material Properties Behind Poor Machinability

Machinability describes how easily a material can be cut under specified conditions. Metals that are hardest to CNC machine usually share several material characteristics that complicate chip formation, heat removal, and tool wear.

Hardness and Strength

High hardness and tensile strength increase cutting forces and accelerate tool wear. Hardened steels, tool steels, and some cobalt-chromium alloys require abrasively resistant tools and carefully managed cutting conditions.

- High yield and tensile strength lead to greater cutting loads and deflection.

- High hardness promotes abrasive wear, chipping, and micro-fracture of the cutting edge.

- High compressive strength impedes plastic deformation during chip formation, raising cutting temperatures.

Toughness, Ductility, and Chip Formation

Tough, highly ductile alloys may not break chips easily. Instead, they form long, continuous chips that can wrap around the tool or workpiece, disrupt coolant delivery, and cause chatter.

Examples include many nickel-based superalloys and austenitic stainless steels at lower hardness levels. Their toughness also increases the energy required for cutting and contributes to higher tool stresses.

Work Hardening Behavior

Work hardening is the tendency of a metal to become harder and stronger when plastically deformed. All machining operations involve localized plastic deformation in the shear zone, at the tool-workpiece interface, and sometimes on the machined surface.

Metals with high work hardening rates (e.g., austenitic stainless steels, some nickel alloys) can rapidly increase in hardness just ahead of the cutting edge, making subsequent passes more difficult and magnifying tool wear if cutting parameters, tools, and coolant application are not optimized.

Thermal Conductivity and Heat Resistance

Metals with low thermal conductivity, or very high operating temperature capability, tend to hold heat in the cutting zone. Nickel-based superalloys and titanium alloys are typical examples.

Consequences include:

- High interface temperatures and rapid thermal softening of conventional tool materials.

- Increased chemical and diffusion wear in carbide tools.

- Thermal expansion and localized phase transformations affecting dimensional accuracy and surface integrity.

Elastic Modulus and Deflection

A low elastic modulus increases deflection of the workpiece and sometimes of the tool, especially for slender parts, thin walls, or long overhangs. Titanium alloys and some nickel alloys have relatively low stiffness compared with hardened steels.

Deflection contributes to dimensional inaccuracy, taper, chatter, and irregular surface finish. It also complicates tolerance control in thin-walled aerospace structures or small biomedical components.

Abrasive Phases and Chemical Reactivity

Some difficult-to-machine metals contain hard, abrasive carbides, nitrides, borides, or intermetallics. Others are chemically reactive with common tool materials at elevated temperatures.

Effects include:

- Abrasive wear and micro-chipping of cutting edges (e.g., in hardened tool steels and cobalt-chrome alloys).

- Adhesive wear and built-up edge formation in reactive alloys such as titanium and some stainless steels.

- Diffusion wear and crater wear where strong chemical affinity exists between tool and workpiece materials.

Overview of Commonly Hard-to-Machine Metals

The metals described below are frequent in aerospace, energy, medical, defense, and tooling applications. Their poor machinability stems from combinations of the properties discussed above.

| Metal / Alloy Category | Typical Examples | Key Machining-Related Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel-based superalloys | Inconel 718, Inconel 625, Hastelloy C-276, Waspaloy | High strength at temperature, low thermal conductivity, severe work hardening, abrasive carbides, strong tool–chip adhesion |

| Titanium alloys | Ti-6Al-4V, Ti-6Al-7Nb, Ti-5553 | Low thermal conductivity, low modulus, high strength-to-weight ratio, chemical reactivity with tools |

| Hardened steels and tool steels | AISI D2, H13, M2, A2, bearing steels | High hardness, abrasive carbides, high compressive strength, risk of thermal cracking and surface damage |

| Cobalt-chromium alloys | CoCrMo, Stellite-type alloys | High hardness and strength, abrasive phases, work hardening, poor heat conduction |

| Tungsten and tungsten heavy alloys | Pure W, W–Ni–Fe, W–Cu | Very high hardness and strength, brittleness, high cutting forces, tool edge chipping |

| Refractory metals (other than W) | Molybdenum, tantalum, niobium | High melting points, variable ductility, sometimes strong chemical reactivity and low thermal conductivity |

| Precipitation-hardened stainless steels | 17-4PH, 15-5PH | High strength in aged condition, work hardening, tendency to build-up edge and poor chip control |

| Austenitic stainless steels | 304, 316, 316L | Work hardening, toughness, built-up edge, long chips, low thermal conductivity compared with carbon steels |

Nickel-Based Superalloys

Nickel-based superalloys are widely used where extreme temperature strength and corrosion resistance are required, such as gas turbine hot sections, nuclear components, and chemical process equipment. Common alloys include Inconel 718, Inconel 625, Hastelloy C-276, and Waspaloy. These alloys are among the hardest metals to CNC machine on a routine basis.

Material Behavior Relevant to Machining

Nickel-based superalloys exhibit:

- High tensile and yield strength up to elevated temperatures.

- Low thermal conductivity (often roughly one-fourth that of carbon steel).

- Abundant hard precipitates and carbides responsible for abrasion.

- Severe work hardening in the cutting zone.

The combination of thermal and mechanical properties keeps the cutting temperature high at the tool–chip interface while chip formation remains highly resistant, causing rapid tool degradation if parameters are not tightly controlled.

Typical Cutting Parameters

Cutting speeds for turning or milling nickel-based superalloys are typically much lower than for aluminum or free-machining steels. Example ranges (actual values depend on tool material, insert geometry, coolant delivery, rigidity, and depth of cut):

Typical speed ranges:

- Carbide turning: approximately 20–60 m/min (65–200 sfm).

- Carbide milling: approximately 20–80 m/min (65–260 sfm).

- Ceramic or cBN turning (finishing): possible speeds above 150 m/min, depending on grade and setup.

Feed per revolution and feed per tooth are often kept moderate to avoid excessive loads on the cutting edge while still ensuring adequate chip thickness to minimize rubbing and work hardening.

Tool Materials and Geometry

Typical tool materials for nickel-based superalloys include:

- High-quality coated carbide inserts with wear-resistant and heat-stable coatings.

- Ceramic inserts (SiAlON or whisker-reinforced) for rough turning or high-speed finishing operations on rigid setups.

- PCBN (polycrystalline cubic boron nitride) in certain finishing operations, particularly where hardened conditions or mixed hard phases are present.

Sharp cutting edges, positive rake, and controlled edge preparation are used to reduce cutting forces and heat generation. However, too sharp an edge may be fragile and chip prematurely, so balanced geometry selection is important.

Process Considerations and Common Issues

Common machining issues include short tool life, notch wear near the depth of cut line, crater wear on rake faces, and deformation or smearing of the machined surface. Intensive coolant delivery, preferably high-pressure through-tool coolant, is widely used to evacuate chips and limit thermal damage.

Multi-axis strategies in milling, stable engagement conditions, and minimized tool overhang are central to maintaining dimensional accuracy and preventing chatter in demanding applications such as turbine disks or blisks.

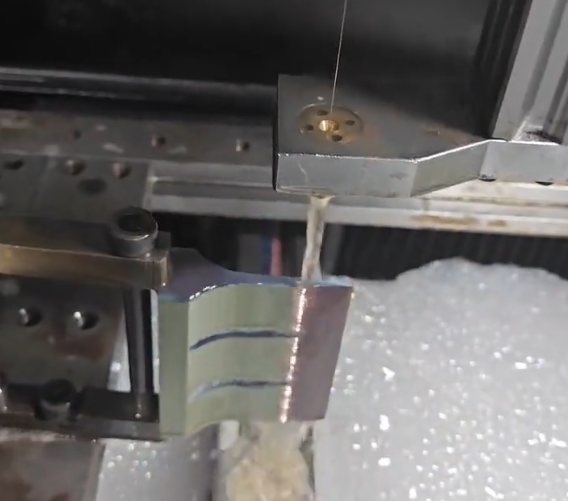

Titanium and Titanium Alloys

Titanium alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V are critical in aerospace structures, engine components, and medical implants because of their high strength-to-weight ratio, corrosion resistance, and biocompatibility. From a CNC machining perspective, titanium is often considered one of the most difficult metals to cut consistently.

Machining-Relevant Properties

Key properties affecting machinability include:

- Low thermal conductivity leading to high cutting temperatures concentrated at the tool tip.

- Medium to high strength combined with relatively low modulus of elasticity.

- High chemical reactivity with common tool materials at elevated temperatures.

The low elastic modulus allows workpieces to deflect under cutting forces, making thin-walled parts and long slender features particularly challenging. The reactive nature and high interface temperatures promote built-up edge and diffusion wear in carbide tools.

General Parameter Ranges

Indicative cutting speeds for Ti-6Al-4V with modern coated carbide tooling:

- Turning: roughly 30–90 m/min (100–300 sfm).

- Milling: roughly 30–120 m/min (100–400 sfm), often on the lower end for heavy engagement.

Feed rates are chosen to maintain a reasonable chip thickness, often in the range of 0.05–0.3 mm/rev for turning or 0.03–0.2 mm/tooth for milling, depending on operation type, tool diameter, and rigidity.

Tooling and Coolant Practices

Carbide tools with tough substrates and heat-resistant coatings are common. Sharp, positive-rake geometries are used to minimize heat and pressure. However, consistent edge strength is required to avoid chipping.

Thorough application of coolant is frequently used, often through-tool delivery, to manage heat and evacuate chips. In some high-speed finishing operations on stable setups, limited or no coolant (controlled dry or near-dry machining) can be used, but this requires careful control of speed, feed, and engagement.

Thin-Walled Structures and Deflection

One of the main practical difficulties with titanium machining is maintaining tolerance and surface integrity in thin-walled or pocketed structures. The combination of workpiece deflection, residual stresses, and cutting forces can cause geometric inaccuracies and vibration.

Strategies often include using light radial engagement, multiple finishing passes with reduced depth of cut, and optimized tool paths to distribute cutting forces uniformly. Rigid fixturing and appropriate selection of step-down and step-over are critical for dimensional control.

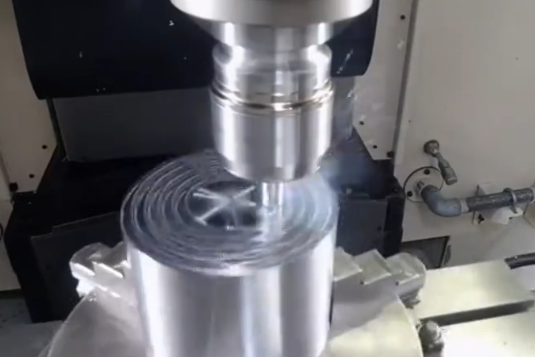

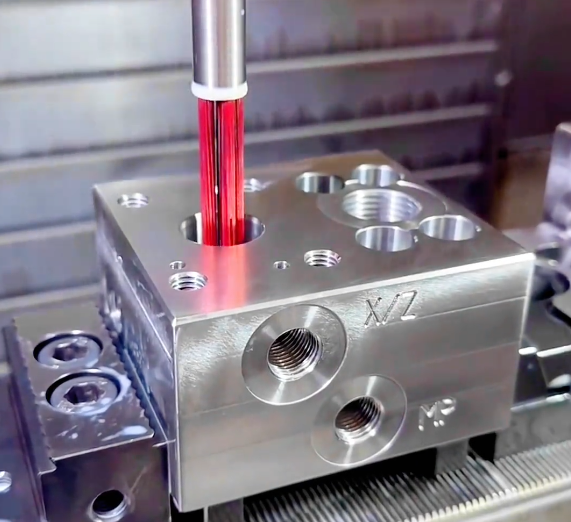

Hardened Steels and Tool Steels

Hardened steels, including tool steels and bearing steels, are used extensively in dies, molds, cutting tools, and high-load machine components. Machining hardened steels requires dealing with high hardness, abrasive carbides, and risk of surface damage such as micro-cracking or white-layer formation.

Typical Hardness Levels and Effects

Common hardness ranges include:

- Quenched and tempered tool steels: frequently 48–62 HRC.

- Bearing steels: typically around 58–64 HRC.

At these hardness levels, conventional high-speed steel tools are generally unsuitable for efficient machining, and even carbide must be carefully selected and applied. The hard phases and high strength generate substantial cutting pressures and abrasive wear.

Common Machining Approaches

There are two broad approaches to machining hardened steels:

- Hard turning and hard milling as a replacement or complement to grinding.

- Conventional or semi-hard machining at intermediate hardness followed by heat treatment and final grinding.

Hard turning often uses PCBN tools at speeds ranging from approximately 80–250 m/min, with light depths of cut and relatively small feeds. Hard milling may employ solid carbide or cBN tools, with high spindle speeds but small step-overs and depths of cut to maintain tool life and surface quality.

Tool Materials and Wear Mechanisms

For high-hardness conditions, PCBN is widely used due to its resistance to abrasive wear and high-temperature stability. Cermet and ceramic tools are also applied in some operations, generally with controlled engagement and requiring rigid setups.

Wear mechanisms include abrasive wear, micro-chipping, and thermal cracking when interrupted cutting or inadequate coolant management leads to large temperature variations. In mold and die work, surface integrity is critical, and a controlled process is needed to avoid tensile residual stresses, white layers, or subsurface damage that could impair fatigue life.

Cobalt-Chromium Alloys

Cobalt-chromium alloys are heavily used in medical implants, dental components, and wear-resistant parts. They combine high strength, wear resistance, and corrosion resistance, but they are also among the hardest materials to machine with conventional CNC equipment.

Mechanical and Metallurgical Features

Cobalt-chromium alloys generally exhibit:

- High hardness and strength at both room and elevated temperatures.

- A high fraction of hard carbides and intermetallic phases.

- Work hardening behavior and toughness that complicate chip breaking.

The machining process is dominated by abrasive wear of cutting tools and high cutting forces, even when small chips are taken. Many parts are near-net-shape cast or additively manufactured and then require careful finishing rather than heavy stock removal.

Cutting Parameters and Tools

Typical cutting speeds for cobalt-chromium alloys with coated carbide tools are low, often in the range of 10–40 m/min for turning or milling. PCBN and some ceramic grades may be used in finishing operations where hardness is high and the setup is rigid.

Chip control can be difficult due to toughness and work hardening, so insert geometries with well-designed chip breakers and appropriate feeds are used to avoid continuous chips. High-pressure coolant assists in chip evacuation, especially in internal features.

Application-Specific Considerations

For medical components, surface finish and dimensional precision are critical. Small changes in cutting parameters can significantly influence surface roughness and residual stresses. Burr formation is a frequent issue, particularly at small features, edges, and slots, and often requires subsequent deburring operations or use of specialized cutting strategies to minimize burrs at the source.

Tungsten and Tungsten Heavy Alloys

Tungsten and tungsten-based heavy alloys are used in radiation shielding, counterweights, kinetic energy penetrators, and high-temperature applications. Their mechanical and physical properties make them difficult to machine effectively.

Material Characteristics Influencing Machining

Tungsten exhibits extremely high melting point, high density, and high compressive strength. Pure tungsten can be brittle at room temperature, while tungsten heavy alloys (e.g., W–Ni–Fe) offer some improved toughness but maintain very high density and strength.

Consequences for machining include:

- Very high cutting forces even at small depths of cut.

- Propensity for edge chipping in brittle conditions.

- Potential for micro-cracking in the workpiece if feeds, speeds, or coolant application are inappropriate.

Tooling and Cutting Conditions

Carbide tools with robust edge preparation are typically used. Cutting speeds are low relative to aluminum or common steels, often on the order of 10–40 m/min, with feeds chosen to minimize rubbing while avoiding excessive chip load on fragile edges.

Because of high density and potential brittleness, fixturing needs to provide excellent support, especially for small or thin parts. Negative rake angles can improve edge strength but at the cost of increased cutting force; positive rakes reduce force but must be balanced against edge durability.

Machined Surface Quality

Maintaining a consistent surface finish on tungsten can be challenging. Small chips, micro-cracks, and localized chipping at corners and edges may require post-machining polishing or grinding. In many applications where dimensional precision is critical, grinding is used as a secondary process after CNC machining to bring parts to final size and surface quality.

Refractory Metals: Molybdenum, Tantalum, and Niobium

Beyond tungsten, other refractory metals such as molybdenum, tantalum, and niobium also present significant machining difficulties. They are used in high-temperature structural components, furnace hardware, and specialized electronics.

General Machining Behavior

Molybdenum, tantalum, and niobium have high melting points and varying ductility depending on purity, grain size, and processing route. They are often quite tough and, in some conditions, prone to galling and built-up edge.

Cutting speeds are usually low, and chip control can be difficult. Burr formation or tearing may occur if tool geometry and feeds are not well matched to the material condition. Because these materials are relatively expensive, minimizing scrap and ensuring process stability is important.

Tool Selection and Coolant Use

Carbide tools with sharp edges and appropriate coatings are used, often with generous coolant to remove heat and reduce tendency to gall. Workholding must be stable to avoid vibration, which can be particularly damaging when machining ductile but strong materials that resist clean chip formation.

Finishing operations may call for very small depths of cut and fine feeds to achieve desired surface integrity, especially for vacuum or high-temperature applications where surface defects can act as initiation sites for failure.

Precipitation-Hardened and Austenitic Stainless Steels

Stainless steels cover a broad range of compositions and conditions. Among them, precipitation-hardened and austenitic grades are frequently identified as relatively hard to machine compared with low-carbon or free-machining steels.

Precipitation-Hardened Stainless Steels

Grades such as 17-4PH and 15-5PH are widely used in aerospace and mechanical components that require high strength and good corrosion resistance. In their aged (hardened) conditions, they achieve high yield strength and enhanced hardness.

Machining issues include:

- High cutting forces and tool wear due to increased hardness and strength.

- Tendency to work harden at the surface if rubbing occurs.

- Chip control difficulties, especially in drilling and boring operations.

Carbide tools with balanced toughness and wear resistance are generally used, often with coated grades designed for stainless steels. Cutting speeds are moderate, and consistent chip thickness is important to avoid rapid work hardening.

Austenitic Stainless Steels

Austenitic grades such as 304 and 316 are ubiquitous in food processing, chemical, and marine environments. While not necessarily as hard as some precipitation-hardened grades, they can be challenging to machine because of high toughness, strong work hardening, and low thermal conductivity compared with carbon steels.

Common machining issues include:

- Rapid work hardening if feeds are too low or tools are dull.

- Long, continuous chips that interfere with coolant delivery and may require chip-breaking inserts.

- Built-up edge and poor surface finish at low cutting speeds or with inappropriate tool geometries.

Using sharp, positive-rake tools designed for stainless steels, adequate coolant, and sufficient feed rates to avoid rubbing is important. In drilling, specialized point geometries and proper chip evacuation are often necessary to prevent workpiece hardening and tool breakage.

Comparison of Difficult-to-Machine Metals

Different metals present different combinations of problems. The following table summarizes selected machinability-related aspects for several typical materials.

| Material Category | Dominant Machining Difficulty | Typical Tooling | Approximate Relative Cutting Speed (vs. free-machining steel) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-based superalloys | High cutting temperature, work hardening, abrasive wear | Coated carbide, ceramics, PCBN | Low (often <30–40%) |

| Titanium alloys | Heat concentration at tool, deflection, chemical reactivity | Coated carbide, high-strength solid carbide | Low (roughly 30–50%) |

| Hardened tool steels | High hardness and abrasive carbides | PCBN, ceramics, high-grade carbide | Low to moderate for hard turning, often <50% |

| Cobalt-chromium alloys | Abrasion, high strength, work hardening | Coated carbide, PCBN for finishing | Low (often <25–35%) |

| Tungsten and heavy alloys | High cutting force, brittleness, edge chipping | Carbide with strong edge prep | Low (often <30–40%) |

| Refractory metals (Mo, Ta, Nb) | Heat, ductility, galling | Sharp carbide, coated carbide | Low to moderate |

| PH stainless steels | High strength, work hardening | Stainless-specific coated carbide | Moderate (roughly 50–70%) |

| Austenitic stainless steels | Work hardening, long chips, built-up edge | Stainless-specific coated carbide | Moderate (roughly 50–70%) |

Issues in CNC Machining of Hard Metals

Across the metals described, several recurring pain points appear in CNC machining environments that handle high-strength and high-temperature alloys.

Tool Life and Tool Cost

Short and unpredictable tool life is a direct consequence of high cutting forces, extreme temperatures, work hardening, and abrasive phases. Frequent tool changes impact machine uptime and labor utilization and create variability in dimensional accuracy and surface finish if offsets are not kept under close control.

Dimensional Accuracy and Stability

Deflection of tools and workpieces, thermal expansion, and inconsistent chip loads can lead to deviations from nominal dimensions, especially on thin walls, long features, and complex 5-axis geometries. Hard turning and milling of hardened steels, or high-strength titanium components, often requires multiple semi-finishing and finishing passes to gradually approach final dimensions while minimizing distortion.

Surface Integrity and Residual Stresses

Surface integrity is a critical concern in many aerospace, power-generation, and medical applications. High cutting temperatures combined with mechanical loading can lead to tensile residual stresses, micro-cracking, or white layers, particularly in hardened steels and nickel-based superalloys.

Where fatigue performance, corrosion resistance, or contact wear are critical, process parameters and tool paths must be selected to limit thermal damage while still achieving required material removal rates.

Chip Control and Coolant Delivery

Long, stringy chips from tough, ductile alloys and insufficient chip breaking can obstruct the cutting zone, damage surfaces, and interfere with coolant flow. High-pressure coolant systems, carefully designed chip breakers, and strategies such as peck drilling or trochoidal milling are frequently used to maintain chip control and temperature management.

General Strategies for Machining the Hardest Metals

Although each metal family requires tailored solutions, several general strategies are applicable when machining difficult metals on CNC machines.

Tool Material and Geometry Optimization

Choosing a tool material with the right combination of toughness, hot hardness, and wear resistance is essential. PCBN and ceramics are often reserved for hardened steels and superalloys in stable, predictable operations. High-performance coated carbides with optimized edge preparation and chip control features are prevalent for titanium, stainless steels, cobalt-chromium, and refractory metals.

Positive rake angles, controlled edge radius, and appropriate chip breaker profiles reduce forces and manage chip formation. However, edge geometry must be robust enough to resist chipping under heavy loads or interrupted cuts.

Selecting Cutting Parameters

Proper selection of cutting speed, feed per tooth or revolution, and depth of cut significantly influences tool life and surface integrity. Generally:

- Speeds are reduced relative to easily machined steels to limit temperature and wear.

- Feeds are kept high enough to avoid rubbing and work hardening but within tool load limits.

- Depth of cut is chosen to balance productivity with the need to avoid notch wear at the depth-of-cut line.

For many difficult metals, controlled entry and exit strategies, modest radial engagement, and constant chip load tool paths improve stability and consistency.

Coolant Application and Heat Management

For metals such as nickel-based superalloys and titanium alloys, concentrated heat at the cutting zone is a primary concern. High-pressure coolant delivered directly to the cutting edge and chip-tool interface helps reduce temperature, flush chips, and dampen built-up edge.

In some finishing operations, controlled dry or minimum-quantity lubrication strategies are used instead of flooding coolant, but this requires careful control of speeds, feeds, and tool engagement to avoid excessive thermal loading.

Workholding and Machine Rigidity

Rigid workholding and minimized tool overhang are crucial when machining hard metals. Any flexibility in the system amplifies chatter and deflection, undermining surface finish and dimensional accuracy.

Fixtures must support thin walls and slender features without distorting functional surfaces. Balanced clamping forces and minimized jaw pressure help maintain component shape while ensuring sufficient stability for high cutting loads.

Process Planning and Toolpath Strategy

Process planning for difficult-to-machine metals often emphasizes:

- Roughing with higher material removal rates using robust tools and moderate cutting conditions.

- Multiple semi-finishing passes to reduce residual stresses and deflection effects.

- Finishing with light cuts and stable engagement to achieve final tolerance and surface finish requirements.

Advanced toolpaths that maintain constant engagement and avoid sudden changes in chip thickness can extend tool life and deliver more uniform surfaces. For five-axis machining of complex geometries in superalloys or titanium, continuous tool orientation control is used to avoid unfavorable cutting angles and localized tool overload.

FAQ About Hard-to-Machine Metals

What are hard-to-machine metals?

Hard-to-machine metals are materials that are difficult to cut, mill, or drill using standard CNC machining processes due to high strength, high hardness, low thermal conductivity, or severe work hardening.

Which metals are considered the most difficult to machine?

Common hard-to-machine metals include titanium alloys, nickel-based superalloys (such as Inconel), hardened steels, tool steels, stainless steels (especially austenitic grades), cobalt-based alloys, and tungsten alloys.

Why are titanium and Inconel difficult to machine?

Titanium and Inconel have low thermal conductivity, causing heat to concentrate at the cutting edge. They also maintain high strength at elevated temperatures, which accelerates tool wear and increases cutting forces.

What challenges occur when machining hard-to-machine metals?

Typical challenges include rapid tool wear, excessive heat generation, work hardening, poor chip control, dimensional inaccuracies, and increased machining costs.

What tools are recommended for machining hard-to-machine metals?

Carbide tools, coated cutting tools (such as TiAlN or AlTiN), ceramic tools, and CBN tools are commonly used. Proper tool geometry and high-pressure coolant systems are also critical.