CNC machining of aluminum and titanium is fundamental to aerospace, automotive, medical, electronics, and general industrial production. Both alloys offer high specific strength and corrosion resistance, but they behave very differently during machining and in service. This article systematically compares CNC machining of aluminum vs. titanium from a technical and engineering perspective.

Material Overview: Aluminum vs. Titanium for CNC Machining

Aluminum and titanium are both lightweight structural metals, yet they differ significantly in density, strength, stiffness, and thermal behavior. Understanding these fundamentals is the basis for rational material selection in CNC machining projects.

| Property | Aluminum Alloy (e.g., 6061‑T6) | Titanium Alloy (e.g., Ti‑6Al‑4V) |

|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ≈ 2.70 | ≈ 4.43 |

| Ultimate tensile strength (MPa) | ≈ 290–320 | ≈ 900–1000 |

| Yield strength (MPa) | ≈ 240–275 | ≈ 830–880 |

| Elastic modulus (GPa) | ≈ 69–72 | ≈ 110–120 |

| Hardness (HV) | ≈ 95–110 | ≈ 330–360 |

| Thermal conductivity (W/m·K) | ≈ 150–180 | ≈ 6–8 |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (µm/m·°C) | ≈ 23–24 | ≈ 8–9 |

Aluminum offers lower density and higher thermal conductivity, making it relatively easy to machine at high cutting speeds. Titanium provides substantially higher strength and corrosion resistance, but with low thermal conductivity that complicates heat evacuation during cutting.

Machinability Comparison

Machinability directly influences cycle time, tool life, surface finish, and dimensional accuracy. Aluminum is considered a highly machinable material, whereas titanium requires more controlled cutting strategies.

Chip Formation and Cutting Forces

Aluminum alloys generate relatively soft, continuous chips, especially in wrought grades such as 6061, 6063, 6082, and 7075. Proper use of chip breakers and sharp cutting edges prevents long, stringy chips and built‑up edge. Cutting forces are moderate, allowing high metal removal rates.

Titanium, particularly Ti‑6Al‑4V, tends to produce tough, segmented chips. Cutting forces are significantly higher for a given depth of cut due to the higher strength of the material. The combination of high strength and low thermal conductivity leads to elevated cutting temperature at the tool–chip interface, which increases tool wear and may cause edge chipping if cutting parameters are too aggressive.

Cutting Speeds and Feeds

Typical cutting parameters differ sharply between aluminum and titanium. Actual values depend on tool material, coating, machine rigidity, coolant delivery, and specific alloy, but the approximate ranges illustrate the contrast.

| Parameter | Aluminum (e.g., 6061) | Titanium (e.g., Ti‑6Al‑4V) |

|---|---|---|

| Cutting speed, Vc (m/min) – carbide tools | 250–800 | 30–90 |

| Feed per tooth, fz (mm/tooth) | 0.05–0.25 | 0.02–0.10 |

| Radial depth of cut, ae (mm) | 0.1–1.5 × tool diameter (depending on strategy) | 0.05–0.5 × tool diameter (often reduced for heat control) |

| Axial depth of cut, ap (mm) | Up to full flute length in roughing (with proper setup) | Limited to maintain stability and avoid chatter |

| Typical metal removal rate (roughing) | High | Moderate to low |

Aluminum permits very high spindle speeds and feed rates, leading to short cycle times. Titanium requires significantly lower cutting speeds and more conservative engagement to protect tools and maintain dimensional stability.

Tool Wear Behavior

During aluminum machining, tool wear is dominated by abrasion and built‑up edge formation. Built‑up edge can affect surface finish and dimensional accuracy, but it can be mitigated with sharp tools, appropriate rake angles, and reliable coolant or lubrication. Tool life is typically long, especially with modern carbide or PCD (polycrystalline diamond) tools.

In titanium machining, adhesive and diffusion wear mechanisms are prominent. Heat is concentrated at the cutting edge, causing rapid flank and crater wear. Titanium can chemically react with tool materials at elevated temperatures, further reducing tool life. This requires careful selection of tool grade and coating, controlled cutting parameters, and effective high‑pressure coolant to extend tool life.

Tooling Strategies for Aluminum and Titanium

Tool material, geometry, and coating selection is critical to achieving efficient CNC machining performance.

Tool Materials

- Aluminum: Solid carbide tools are standard for milling and drilling. Uncoated or TiB2‑coated cutters are often preferred for reducing built‑up edge. PCD and CBN tools are used for very high volume production and ultra‑high surface finish requirements, especially in automotive and electronics housings.

- Titanium: Fine‑grain or ultra‑fine‑grain carbide tools are commonly used. Cobalt‑enriched carbides provide increased toughness to resist chipping. High‑speed steel may be used for some operations but is generally less productive. Ceramic and CBN tools are applied selectively in high‑speed finishing, with strict control of engagement to avoid catastrophic failure.

Tool Geometry

For aluminum, sharp cutting edges with high positive rake angles and polished flutes are beneficial. Large chip gullets promote efficient chip evacuation. Helix angles around 35–45° are common for end mills, with 2‑ or 3‑flute designs supporting high chip load per tooth.

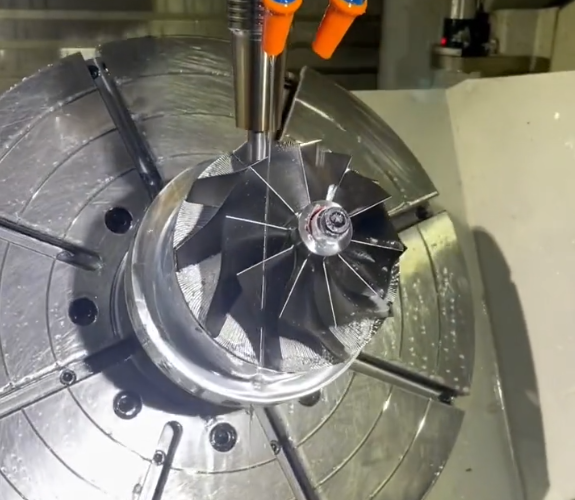

For titanium, tool geometry favors high edge strength and reduced friction. Moderate positive rake with adequate edge reinforcement, optimized clearance angles, and variable helix designs can help suppress chatter. 4‑ to 6‑flute cutters tailored for titanium are employed for stable roughing and finishing, especially in high‑rigidity setups.

Tool Coatings

In aluminum machining, coatings are optional. When used, they must prevent built‑up edge without reacting chemically with aluminum. TiB2, DLC (diamond‑like carbon), or certain non‑stick coatings are commonly applied. PCD tools offer very low friction and long life in high‑speed milling of abrasive aluminum alloys with high silicon content.

In titanium machining, wear‑resistant coatings are essential. TiAlN, AlTiN, and related nano‑layer coatings withstand high thermal loads and reduce diffusion wear. Coatings must have good adhesion and be optimized for high‑temperature stability. Some cutters combine advanced coating systems with micro‑polished cutting edges to balance wear resistance and sharpness.

Thermal Behavior and Heat Management

Heat generation and dissipation are key factors distinguishing aluminum and titanium machining behavior.

Aluminum’s high thermal conductivity allows heat to be carried away in the chips and workpiece, reducing thermal load on the tool. This property supports higher cutting speeds and permits both flood coolant and minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) strategies. However, aluminum’s relatively high coefficient of thermal expansion means dimensional changes must be considered in precision machining, particularly for large parts and long machining cycles.

Titanium’s low thermal conductivity localizes heat at the cutting edge and in the immediate cutting zone. This significantly raises tool temperature and intensifies wear. High‑pressure, high‑flow coolant directed precisely to the cutting zone is widely used to evacuate chips and maintain tool life. Balanced heat control is necessary to limit thermal deformation and avoid microstructural changes in critical aerospace or medical components.

Dimensional Accuracy and Tolerances

Both materials can achieve tight tolerances with properly configured CNC machines, but process strategies differ.

Aluminum tends to be more stable under machining loads due to lower cutting forces. It is relatively straightforward to achieve tolerances in the range of ±0.01 mm for precision features on rigid setups. Thermal expansion of the workpiece must be considered for long cycles or large components. Machining strategies may include intermediate cooling pauses or temperature compensation in CAM to preserve accuracy.

Titanium’s higher cutting forces and tendency to spring back after cutting can cause elastic deformation, leading to undersized or distorted features if clamping and tool paths are not carefully designed. Achieving comparable tolerances often requires:

- More robust fixturing to minimize workpiece deflection

- Reduced depth of cut and feed in finishing passes

- Multiple semi‑finishing and finishing passes to gradually approach final dimensions

In thin‑walled titanium structures, common in aerospace applications, dimensional control becomes more sensitive to tool engagement and direction of cut. This may increase machining time compared with similar aluminum structures.

Surface Finish and Surface Integrity

Surface finish requirements vary by application: aesthetics in consumer electronics, fatigue life in aerospace, or bio‑compatibility in medical implants. CNC machining solutions must address both roughness and subsurface integrity.

Aluminum typically yields very good surface finish with appropriate cutting parameters. Ra values below 0.8 µm are readily achievable in finishing operations, and Ra < 0.4 µm is possible with optimized tools and conditions. Avoiding built‑up edge is the main consideration, as it can cause surface tearing or smearing.

Titanium surfaces require more attention. The material’s tendency to work‑harden and generate heat can affect surface integrity. Excessive temperature may produce a heat‑affected layer with altered microstructure, which in turn influences fatigue performance. Finishing strategies for titanium often use lower feed rates and sharp, well‑cooled tools to maintain specified surface quality while limiting residual tensile stresses.

Fixturing and Workholding Considerations

Workholding influences stability, accuracy, and surface quality. Material stiffness and cutting force levels dictate different practices for aluminum and titanium.

Aluminum parts are generally lighter and more flexible, but cutting forces are modest. Standard vises, clamps, and modular fixtures are sufficient for many applications. Vacuum fixtures and soft jaws are frequent choices for thin‑wall housings or plate‑like components because they distribute clamping force and protect delicate surfaces.

Titanium components experience higher cutting forces and are often used in structural applications where geometry is complex and stiffness varies across the part. Fixturing must ensure:

- Uniform support of thin walls and ribs to reduce chatter and deflection

- Secure clamping to resist tool forces without inducing excessive residual stress

- Accessibility for multi‑axis machining to avoid repeated re‑clamping

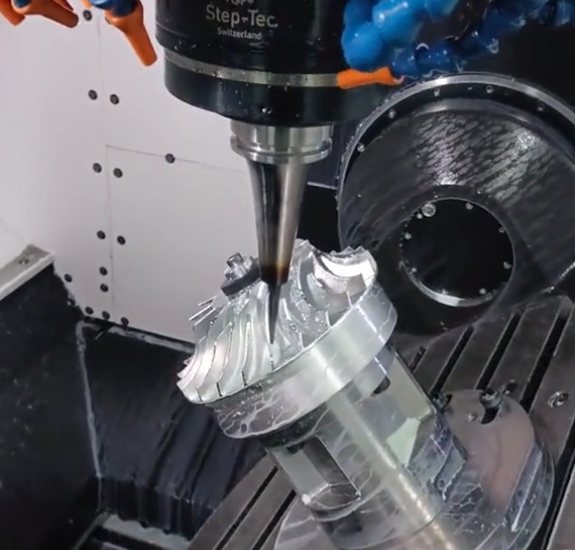

Multi‑axis (4‑ or 5‑axis) CNC machines combined with carefully designed fixtures can reduce setup counts and minimize positional error buildup, which is especially beneficial for high‑precision titanium components.

Material Grades Commonly Used in CNC Machining

Different alloy grades within aluminum and titanium families offer specific trade‑offs in strength, machinability, and corrosion resistance.

Typical Aluminum Grades

Common CNC‑machined aluminum alloys include:

- 6000 series (e.g., 6061‑T6, 6082‑T6): Widely used for structural parts, fixtures, machine components, and general‑purpose applications. Good balance of strength, corrosion resistance, and machinability.

- 7000 series (e.g., 7075‑T6): High‑strength aluminum for aerospace components, high‑performance sporting goods, and critical structural elements. Machinability remains good, though partially reduced compared with 6000 series. Offers higher mechanical strength but may require additional corrosion protection in some environments.

- 5000 series (e.g., 5052, 5083): Often used when improved corrosion resistance is required, such as in marine or chemical environments. Machinability is acceptable but may be slightly less favorable than 6000 series depending on temper.

Typical Titanium Grades

In titanium machining, the following grades are frequent:

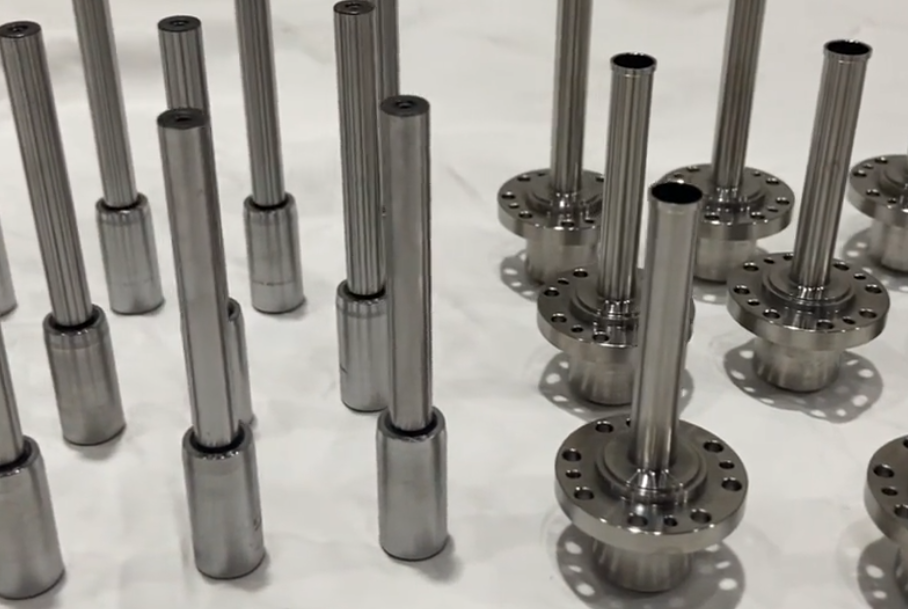

- Ti‑6Al‑4V (Grade 5 and Grade 23 / ELI): The most widely used titanium alloy for aerospace structures, turbine components, and medical implants. High strength‑to‑weight ratio, good fatigue performance, and excellent corrosion resistance. Machining is demanding but well documented.

- Commercially pure (CP) titanium (Grades 1–4): Lower strength than Ti‑6Al‑4V but excellent corrosion resistance and good biocompatibility. Used in chemical processing equipment, medical devices, and marine environments. Machinability is still more challenging than aluminum but somewhat less severe than Ti‑6Al‑4V.

Cost and Production Efficiency

Cost evaluation includes raw material, machining time, tooling, and quality assurance. Aluminum and titanium differ significantly in each of these factors.

Aluminum is relatively inexpensive and widely available in plates, bars, and extrusions. High machinability reduces cycle times and extends tool life, improving throughput and lowering unit costs. For medium to high production volumes, aluminum components can be produced efficiently on standard CNC mills and lathes. Quality control is straightforward, and scrap recycling is simple.

Titanium is more expensive as a raw material and requires specialized processing routes. Machining times are longer due to reduced cutting speeds and the need for multiple passes to maintain stability. Tooling costs are higher because tool wear is accelerated and often demands premium carbide grades and advanced coatings. Machine tool requirements are stricter: high rigidity, powerful spindles, and reliable coolant systems are important to achieve consistent productivity.

For high‑value applications where weight reduction, strength, or bio‑compatibility are critical, these increased costs are justified. In general‑purpose industrial applications where such properties are not mandatory, aluminum usually offers a more cost‑effective solution.

Application Suitability

Selection between CNC‑machined aluminum and titanium should be driven by functional requirements, environmental conditions, and cost targets.

Aluminum Applications

Aluminum is well suited to:

- Electronics housings, heat sinks, and communication equipment where thermal conductivity and lightweight construction are beneficial.

- Automotive and transportation components requiring reduced mass without extreme service temperatures or loads.

- General mechanical parts, fixtures, machine frames, and prototypes where good machinability and moderate strength are sufficient.

- Aerospace components where high strength aluminum (e.g., 7075) meets design requirements and titanium is not strictly necessary.

Titanium Applications

Titanium is preferred when:

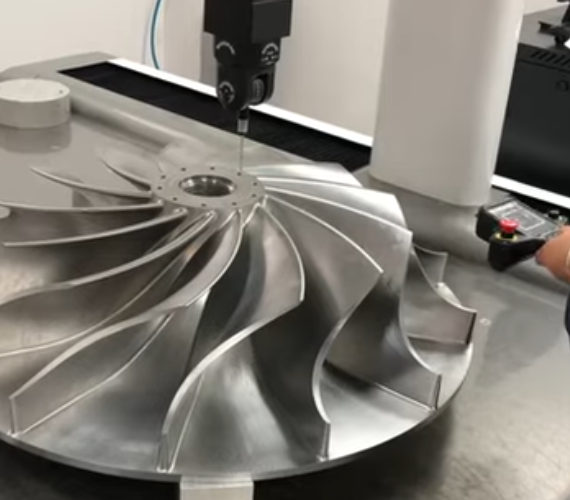

- High strength‑to‑weight ratio is essential in combination with corrosion resistance, as in aerospace structures and turbine engine components.

- Bio‑compatibility is required, such as orthopedic implants, dental implants, and surgical instruments.

- Parts face aggressive media, elevated temperatures, or cyclic loading conditions that demand consistent performance and long service life.

- Weight reduction must be achieved without compromising fatigue strength, particularly in high‑performance sports and racing sectors.

Design Considerations When Choosing Aluminum or Titanium

Engineering design choices determine whether aluminum or titanium is the more appropriate CNC machining material. Designers must consider mechanical loads, environment, manufacturability, and cost simultaneously.

For aluminum, design freedom is high. Thin walls, complex internal cavities, and intricate features can be machined efficiently, especially on multi‑axis machines. Larger features and deep pockets remain economical due to high metal removal rates. However, designers should consider:

- Minimum wall thickness appropriate to stiffness and vibration, especially in long, slender geometries.

- Potential distortion from internal stress release during machining, particularly in thick or heavily stressed extrusions.

- Surface treatments such as anodizing or conversion coatings when additional corrosion protection or wear resistance is required.

For titanium, design should minimize excessive stock removal because each cubic centimeter of material removed incurs significant machining time and tool wear. Considerations include:

- Optimization of blank geometry (e.g., near‑net‑shape forgings) to reduce machining volume.

- Balancing wall thickness for weight saving with the need for stiffness to resist machining loads.

- Ensuring sufficient fillet radii and avoiding sharp internal corners to reduce stress concentration and simplify tool paths.

Both materials benefit from early collaboration between design engineers, manufacturing engineers, and machinists to ensure that performance targets and manufacturability are aligned.

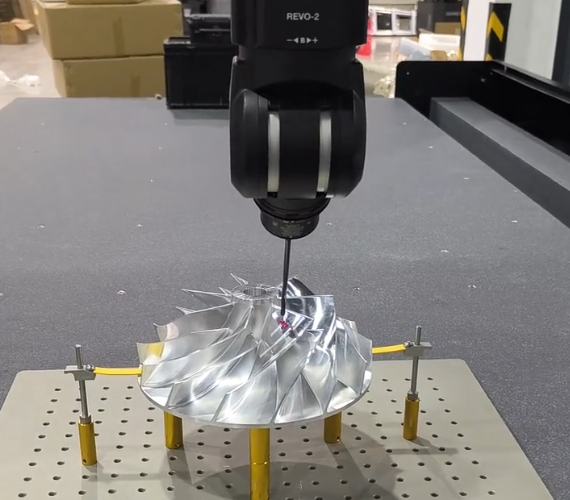

Quality Control and Inspection

Inspection requirements differ according to application criticality and material characteristics.

For aluminum parts, standard dimensional inspection using CMMs, optical systems, and gauges is generally sufficient. Surface finish, flatness, and positional tolerances are routinely controlled. For aerospace or critical mechanical components, additional measurements such as residual stress assessment or non‑destructive testing (NDT) may be introduced.

For titanium, quality control is often more stringent due to the typical application domains. Aerospace and medical components may require:

- High‑accuracy CMM inspection for complex geometries and tight tolerances.

- NDT methods such as dye penetrant testing, ultrasonic inspection, or radiographic testing to detect internal or surface defects.

- Documentation of process parameters, tool condition, and traceability of material certificates.

The low thermal conductivity of titanium can leave internal residual stress if heat is not adequately managed, so process qualification is especially important for long‑term reliability.

Environmental and Recycling Considerations

Aluminum and titanium are both recyclable, but their recycling routes and energy footprints differ.

Aluminum is one of the most recycled industrial metals. Recycled aluminum requires significantly less energy to produce than primary aluminum from ore, and established scrap collection and re‑melting systems exist worldwide. In machining operations, chips and offcuts are easily segregated and sold as scrap, contributing to overall resource efficiency.

Titanium recycling infrastructure is more specialized. Titanium scrap has high value, especially in the aerospace supply chain, but sorting and re‑melting require dedicated processes. Machining chips must be kept clean and separated from other metals to maintain their value. While titanium production is energy‑intensive, its long service life and performance in demanding applications can offset initial energy input over the lifecycle of the component.

Summary: Choosing Between CNC Machined Aluminum and Titanium

Aluminum excels in machinability, cost efficiency, and thermal conductivity, enabling high‑speed CNC machining for a wide variety of parts. It is widely used wherever moderate to high strength, low weight, and good corrosion resistance are sufficient, especially in general engineering, transportation, and electronics.

Titanium provides superior strength‑to‑weight ratio, excellent corrosion resistance, and bio‑compatibility, making it indispensable in aerospace, medical, and high‑performance applications. Its machining requires careful control of cutting parameters, tooling, heat management, and fixturing, which increases cost and complexity but delivers components with exceptional performance in demanding environments.

Material selection for CNC machining should be based on quantifiable requirements such as load, stiffness, temperature range, environment, expected lifetime, dimensional tolerances, and budget. By understanding the distinct behaviors of aluminum and titanium in CNC machining, engineers and buyers can make informed decisions that balance performance and manufacturing efficiency.

FAQ: CNC Machining Aluminum vs. Titanium

Is aluminum or titanium easier to machine on CNC equipment?

Aluminum is significantly easier to machine. It supports much higher cutting speeds and feed rates, generates lower cutting forces, and produces chips that are easier to manage. Tool life is longer and setup requirements are less demanding. Titanium requires reduced cutting speeds, more rigid fixturing, specialized tooling, and careful heat management to avoid rapid tool wear and dimensional issues.

When should aluminum be chosen over titanium?

Choose aluminum for prototypes, cost-sensitive parts, electronics housings, and components needing good machinability and thermal conductivity.

What is the main difference between machining aluminum and titanium?

Aluminum is much easier to machine due to its softness and high machinability, while titanium is harder, generates more heat, and causes greater tool wear.

Why is CNC machining titanium more expensive?

Titanium is harder to cut, requires slower speeds, specialized tooling, and increases tool wear—all of which raise machining costs.

Is aluminum or titanium lighter?

Aluminum is significantly lighter, but titanium offers more strength at a slightly higher weight.