Custom sensor housings protect sensitive electronics, provide mechanical interfaces, and ensure reliable operation in real-world environments. Among the most commonly used fabrication methods for these housings are 3D printing and CNC machining. Each method has technical advantages and constraints related to accuracy, strength, materials, cost, and manufacturability.

This guide systematically compares 3D printing and CNC machining for custom sensor housings, from early prototyping to low- and medium-volume production. It focuses on measurable parameters and practical decision criteria for engineers, product developers, and manufacturing professionals.

Functional Roles and Requirements of Sensor Housings

Before comparing manufacturing methods, it is essential to clarify what a sensor housing must achieve. Technical requirements vary widely depending on application, but the main functional roles are relatively consistent.

Environmental Protection

Sensor housings act as a barrier between the environment and the sensing element, PCB, and wiring. Typical environmental protection requirements include:

- Ingress protection (dust, water, moisture)

- Temperature and humidity tolerance

- Chemical and UV resistance

Many industrial or outdoor sensors target IP54 to IP67 ratings, which demand precise fits, reliable seals, and controlled surface finishes at sealing interfaces.

Mechanical and Structural Functions

Mechanical aspects define how the housing withstands loads and interacts with other components:

- Resistance to impact, vibration, and fatigue

- Dimensional stability across temperature range (e.g., −20 °C to +80 °C or wider)

- Provision of mounting features (bosses, flanges, brackets, dovetails)

Requirements for stiffness, impact resistance, and allowable deformation directly influence material choice and wall thickness, which in turn affect manufacturability via 3D printing or CNC machining.

Electrical and Electromagnetic Considerations

Electrical and EMC (electromagnetic compatibility) aspects are frequently critical:

- Electrical insulation or conductivity, depending on design

- EMI/RFI shielding for sensitive circuitry

- Grounding paths and isolation distances

Metal housings provide natural shielding but introduce risks of short circuits without proper isolation. Plastic housings may need metallization, coatings, or internal shields to meet EMC requirements.

Integration and Assembly

Housing design governs assembly complexity and field serviceability. Key factors include:

Fastening methods (screws, snap-fits, bayonet locks), cable glands and overmolded connectors, O-rings and gaskets, and space allocation for PCB, connectors, and potting compounds. Manufacturing method affects how easily fine features can be produced and how repeatable their dimensions are across batches.

Overview of 3D Printing for Sensor Housings

3D printing, or additive manufacturing, builds parts layer by layer from a digital 3D model. For sensor housings, it is widely used for prototypes, functional test units, and small production runs.

Main 3D Printing Technologies Used for Housings

Several additive processes are relevant to sensor housings, each with specific suitability in terms of detail, strength, and material range.

Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM/FFF)

FDM extrudes thermoplastic filament through a heated nozzle. Common materials: PLA, ABS, PETG, PC, PA (nylon), and filled composites (glass fiber, carbon fiber).

Typical performance ranges:

- Layer height: 0.1–0.3 mm for functional parts

- Dimensional tolerance (well-tuned machines): ±0.1–0.3 mm across 100 mm

- Surface roughness (Ra): ~10–25 µm without post-processing

FDM is attractive for quickly iterating housing designs, adding internal channels or complex mounting features, and producing larger enclosures at relatively low cost. However, anisotropy along the layer direction, visible layer lines, and limited fine detail may restrict its use in high-precision or highly sealed enclosures.

Stereolithography (SLA) and Digital Light Processing (DLP)

SLA and DLP cure liquid resin photochemically using a laser or projected light. They offer high resolution and smooth surfaces, suitable for intricate housings and small form-factor sensors.

Typical parameters:

- Layer height: 0.025–0.1 mm

- Dimensional tolerance: ±0.05–0.15 mm across 100 mm (depends on resin and machine)

- Surface roughness (Ra): ~1–5 µm without extensive post-finishing

Engineering resins (tough, high-temperature, flexible, ESD-safe) allow functional housings with good detail. Drawbacks include resin brittleness for some materials, sensitivity to UV over time, and handling/post-curing requirements. For IP-rated enclosures, careful post-curing and gasket design are necessary to maintain dimensional stability.

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) and Multi Jet Fusion (MJF)

SLS and MJF fuse powdered polymers (primarily PA12, PA11 and their derivatives) using lasers or infrared energy. Parts are supported by surrounding powder, enabling complex geometries without support structures.

Typical characteristics:

- Layer height: 0.06–0.15 mm

- Dimensional tolerance: ±0.1–0.2 mm across 100 mm

- Surface roughness (Ra): ~6–12 µm, slightly grainy texture

Mechanical properties are generally more isotropic than FDM, and nylon materials are robust, chemically resistant, and suitable for many industrial sensor housings. SLS/MJF is often used for low- to mid-volume batches where tooling is not justified.

Metal 3D Printing for Specialized Housings

For extreme environments (high pressure, high temperature, aggressive chemicals) or when integrated shielding is required, metal additive processes such as Selective Laser Melting (SLM) or Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) can be considered.

Typical properties:

- Dimensional tolerance: ±0.1–0.2 mm (often followed by CNC finishing of critical interfaces)

- Materials: stainless steel (e.g., 316L), aluminum, titanium alloys

- Excellent temperature resistance and strength

Metal additive manufacturing is usually reserved for applications where performance requirements justify higher cost and more complex post-processing.

Overview of CNC Machining for Sensor Housings

CNC machining is a subtractive process in which material is removed from a solid block (stock) using computer-controlled cutters. For sensor housings, CNC machining is widely used in both prototyping and production, especially when high precision and robust performance are needed.

Core CNC Processes Relevant to Housings

Most sensor housings can be manufactured using a combination of milling, turning, and drilling. For complex shapes, multi-axis machining or multiple setups are used.

3-Axis and 5-Axis Milling

3-axis milling is suitable for housings with features accessible from the top or from limited directions. 5-axis milling adds rotational freedom, enabling machining of complex geometries, angled surfaces, and undercuts in fewer setups, which enhances accuracy and reduces cumulative error.

Common parameters for precision CNC milling:

- Dimensional tolerance: ±0.02–0.1 mm for most features; tighter for critical dimensions if specified and feasible

- Surface finish: Ra 0.8–3.2 µm for typical machined surfaces without polishing

- Minimum wall thickness: as low as 0.5–1.0 mm for metals, 0.8–1.5 mm for plastics, depending on material and part size

Turning for Cylindrical Housings

For cylindrical sensor bodies (pressure sensors, temperature probes, flow sensors), CNC turning is often the main process. It yields excellent coaxiality and roundness, which are important for sealing and mounting.

Typical capabilities:

- Roundness and concentricity: often within 0.01 mm for precision applications

- Surface finish: Ra 0.4–1.6 µm achievable with appropriate tooling

Materials Commonly Machined for Sensor Housings

CNC machining supports a broad range of engineering materials. For sensor housings, typical selections include:

| Material Category | Examples | Key Attributes for Sensor Housings |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum alloys | 6061-T6, 6082, 7075 | Lightweight, good strength-to-weight ratio, easy machining, good thermal conductivity, can be anodized |

| Stainless steels | 304, 316, 316L | Corrosion resistance, strength, suitable for harsh and marine environments, good for hygienic designs |

| Carbon steels | 1045, 4140 | High strength, may require coatings or plating for corrosion protection |

| Copper alloys | Brass, bronze | Good machinability, corrosion resistance, used for specific electrical or mechanical requirements |

| Engineering plastics | ABS, PC, PA, POM, PEEK | Electrical insulation, lower weight, chemical resistance, lower tooling cost than metals |

Selection depends on environmental exposure, required stiffness, allowable weight, and cost constraints. Machined housings can achieve high repeatability and tight-fitting features, which is beneficial for sealing surfaces and precision alignment.

Design Considerations Specific to 3D Printing

Designing sensor housings for 3D printing requires balancing functionality with process-specific constraints related to layer-based fabrication, support requirements, and thermal behavior.

Wall Thickness and Structural Integrity

Minimum wall thickness depends on process and material:

- FDM plastics: practical minimum 1.2–2.0 mm for structural walls

- SLA resins: 0.8–1.5 mm for non-load-bearing walls; thicker for load-bearing areas

- SLS/MJF nylon: 1.0–1.5 mm typical minimum for functional parts

Thin sections may warp or fail during printing or service, especially along the layer direction. Ribbing and local thickening can improve stiffness without excessively increasing weight.

Anisotropy and Load Orientation

Most 3D-printed plastics exhibit lower strength between layers than within a layer. For sensor housings, this affects:

- Screw boss placement and orientation

- Snap-fit design direction

- Mounting flange orientation relative to expected loads

Where possible, orient the part so that critical load paths are aligned in the plane of the layers, or select processes like SLS that reduce anisotropy.

Dimensional Accuracy and Fit Features

Tolerancing 3D-printed housings requires consideration of machine capabilities and post-processing.

Common practices include:

- Allowing clearance of 0.2–0.5 mm between mating plastic parts, depending on process

- Oversizing holes intended for drilling or reaming post-print

- Using flat gasket surfaces instead of complex sealing profiles if precision is limited

Critical alignment features (sensor windows, optical paths, O-ring grooves) may need post-machining on reference surfaces if tight tolerances are required.

Surface Finish and Sealing Interfaces

Surface quality influences sealing performance and aesthetics. Raw FDM surfaces often require sanding, vapor smoothing, or coating to reduce roughness. SLA provides smoother surfaces suitable for O-rings after minor finishing. SLS/MJF surfaces are matte and slightly porous; sealing surfaces may need additional machining or sealing compounds.

For gasketed seals, common design practices include:

- Flatness tolerance on sealing surfaces based on IP rating requirements

- O-ring groove dimensions consistent with standard O-ring sizes (cross-section and squeeze percentage)

- Avoiding abrupt steps or unsupported edges that may deform under compression

Feature Design for Additive Processes

Additional considerations include:

- Support requirements: overhangs beyond 45–60° may need support (FDM, SLA), increasing post-processing time

- Drainage holes for SLA to avoid trapped resin in cavities

- Escape holes for SLS/MJF to remove unsintered powder from internal cavities

For sensor housings with internal channels, cable routes, or potting cavities, these considerations need to be integrated early into the CAD model.

Design Considerations Specific to CNC Machining

CNC-machined housings must be compatible with tool access, workholding, and material removal strategies. These constraints affect geometry, tolerances, and cost.

Tool Access and Geometry Constraints

Milling tools are typically cylindrical, which imposes constraints on internal corners and deep pockets. Consider the following:

- Internal fillet radius: ideally ≥ tool radius; typical internal corner radii 1–3 mm or larger

- Depth-to-diameter ratio of tools: high aspect ratios increase deflection and risk of chatter

- Undercuts: may require special tools or multi-axis machining

When designing sensor housings with deep cavities for electronics, include sufficient corner radii and limit depth relative to the cavity width when possible.

Wall Thickness and Stability During Machining

Very thin walls can vibrate or deflect under cutting forces, leading to poor surface finish and dimensional deviation. Practical guidelines:

- Metal housings: avoid walls thinner than 0.8–1.0 mm unless necessary and properly supported

- Plastic housings: walls of 1.5–2.5 mm are common to handle machining loads and service use

Where lightweight design is important, pocketing with ribs offers a compromise between stiffness and material removal.

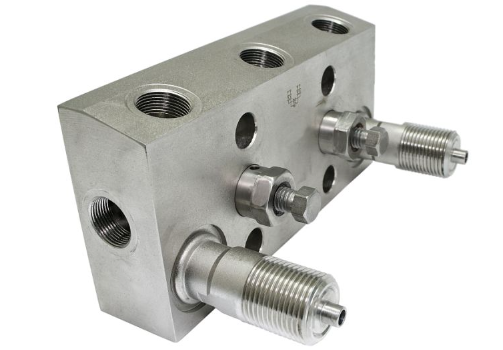

Tolerances, Fits, and Alignment Features

CNC machining is well suited for precision features used in sensor housing design:

- Bored holes and reamed seats for connector shells or alignment pins

- Flat, parallel sealing surfaces

- Precision grooves for O-rings and retaining rings

Typical general tolerances for sensor housings may be ±0.05–0.1 mm, with tighter tolerances on critical sealing or alignment features. Over-specifying tolerances can significantly increase machining time and inspection requirements, so it is important to differentiate between critical and non-critical dimensions.

Fastening and Thread Features

CNC machining can produce robust threads directly in metal or plastic housings. For sensor housings, threads are often required for:

- Enclosure covers (threaded lids)

- Process connections (e.g., G1/4, NPT, M10×1)

- Mounting holes for brackets and panels

In plastics, metal inserts (press-fit or heat-set) improve thread durability. Thread engagement length must be selected to balance pull-out strength with material characteristics.

Surface Finishes and Post-Processing

CNC-machined surfaces may be left as-machined for internal areas, but external and sealing surfaces often undergo additional steps:

- Bead blasting for uniform matte appearance and deburring

- Anodizing of aluminum for corrosion resistance and electrical insulation or conductivity (depending on specification)

- Passivation of stainless steel to enhance corrosion resistance

- Painting or powder coating for environmental protection and labeling

Surface treatment may also affect dimensions slightly, so this must be accounted for when specifying critical fits.

Performance Comparison: 3D Printing vs CNC Machining

Comparing 3D printing and CNC machining for sensor housings involves multiple criteria: accuracy, mechanical performance, sealing capability, surface quality, and repeatability. The following table summarizes typical characteristics for commonly used processes.

| Aspect | 3D Printing (Typical Polymer Processes) | CNC Machining (Metals & Plastics) |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensional accuracy | Approx. ±0.05–0.3 mm, depending on process and size | Approx. ±0.02–0.1 mm typical; tighter possible |

| Surface roughness (Ra) | FDM: 10–25 µm; SLA: 1–5 µm; SLS/MJF: 6–12 µm | Machined: 0.4–3.2 µm typical without polishing |

| Mechanical properties | Anisotropic for many plastics; strength depends on process and orientation | Isotropic bulk material properties; higher strength and stiffness for metals |

| Sealing capability | Feasible with careful design and post-processing; limited by roughness and warping in some processes | Well-suited to precise sealing surfaces, O-ring grooves, and tight fits |

| Material variety | Engineering polymers, some filled composites, limited metals for specialized setups | Broad range of metals and engineering plastics; high-temperature and high-strength options |

| Design freedom | High; complex internal geometries and lattice structures possible | Limited by tool access; internal cavities and undercuts more constrained |

| Batch-to-batch repeatability | Good with stable machines and process control; may require calibration checks | Very high repeatability with controlled fixtures and validated programs |

In practice, CNC machining often provides tighter tolerances and more robust mechanical performance, particularly for metal housings and high IP-rating requirements, while 3D printing offers greater freedom in geometry and shorter lead times for new designs or variants.

Cost and Lead Time Factors

For custom sensor housings, cost structure and lead time are crucial in selecting between 3D printing and CNC machining. Both one-off prototypes and production quantities must be considered.

Tooling and Setup Costs

3D printing generally has low upfront costs. There is no dedicated tooling, and setup typically involves slicing models and preparing build jobs. This is particularly useful when designs are expected to change.

CNC machining requires programming, fixturing, and sometimes custom soft jaws or fixtures for complex housings. Setup time is amortized over the batch size, so it is relatively more expensive for very low quantities but efficient for repeat work.

Per-Part Cost Across Quantity Ranges

3D printing is often cost-effective for:

- Prototypes and engineering samples (1–20 pieces)

- Small batches (e.g., 20–200 pieces) where flexibility is more important than lowest per-unit cost

CNC machining becomes increasingly cost-competitive as quantities grow, due to faster cycle times per part and the ability to run multi-part fixtures or automated production. For metal housings or where long-term production is anticipated, CNC machining usually offers lower per-part cost beyond a certain volume threshold, even without casting tooling.

Lead Time and Iteration Speed

3D printing can deliver functional housings in hours to a few days, depending on queue and post-processing. This enables fast design iterations based on test results or field feedback.

CNC machining lead times depend on programming workload, machine availability, and complexity. Prototyping may take several days to a couple of weeks. However, once a machining process is established, repeat runs can be scheduled quickly with predictable throughput.

Material and Consumable Costs

Material utilization differs significantly between the two methods. 3D printing typically uses only material that becomes part of the part plus support material or unsintered powder (which can often be reused in part). CNC machining removes material from a larger stock, generating chips that may be recycled but still represent wasted material.

For expensive materials (e.g., titanium or high-grade stainless steel), this difference can influence total cost. For common polymers or aluminum alloys, the material portion is often less dominant compared to machine time and labor.

Application-Specific Suitability

The optimal method depends strongly on the application environment, functional requirements, and product lifecycle stage. Different sensor types and use cases emphasize different performance aspects.

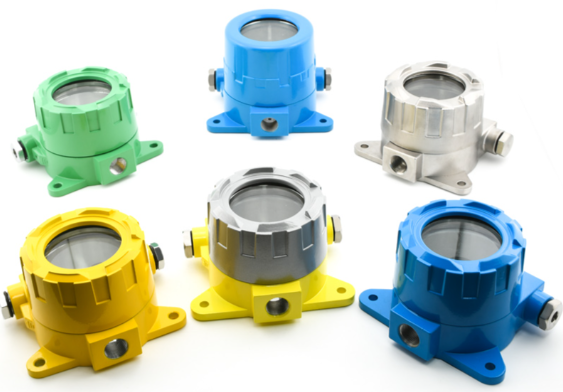

Industrial and Process Sensors

Industrial pressure, flow, temperature, and position sensors often operate in demanding environments with exposure to high pressure, vibration, and chemicals. Key requirements are robust sealing, corrosion resistance, and mechanical durability.

Typical characteristics:

- Process connections with standardized threads or flanges

- Metal housings (stainless steel, aluminum with coatings) for pressure boundaries

- High IP rating (IP65–IP67 or higher), sometimes explosion-proof housings

For such applications, CNC machining of metal housings is generally the primary choice. 3D printing may still be used for internal non-pressure-bearing sub-housings, fixtures, or prototype evaluation, but long-term production housings are commonly machined or cast and machined.

IoT, Smart Home, and Building Automation Sensors

These sensors often operate indoors or in semi-protected environments. Aesthetic requirements and compact form factors are important, while mechanical loads are relatively moderate.

Typical characteristics:

- Plastic housings with integrated snap-fits and complex internal structures

- Wireless modules, antennas, and battery compartments

- Moderate IP rating (IP20–IP54) or higher for certain outdoor units

In this segment, 3D printing is widely used for prototyping and early pilot runs, especially with SLA or SLS for good surface quality and detail. For higher quantities, CNC machining of plastic or aluminum may be used for low-volume production, though injection molding is often considered beyond certain volumes. Sensor housings with integrated antenna windows or translucent sections may require careful material selection and process compatibility.

Automotive and Transportation Sensors

Automotive sensors face vibration, thermal cycling, and exposure to oils, fuels, and road contaminants. Requirements include:

- Temperature resistance across wide ranges (often −40 °C to +125 °C or more)

- Long-term durability under vibration and shock

- Compatibility with automotive fluids and standards

3D printing is frequently used for design validation, packaging studies, and preliminary performance tests. For production housings, CNC machining of metal or high-performance plastics may be used for low-volume or specialized sensors, while high-volume parts typically migrate to molded solutions. CNC machining is well suited for complex multi-part housings that must maintain tight dimensional stability under temperature variations.

Medical and Laboratory Sensors

Sensor housings for medical and laboratory environments may require biocompatibility, sterilization resistance, and chemical resistance to cleaning agents or reagents.

Considerations include:

- Smooth, easy-to-clean surfaces

- Materials compatible with disinfection or sterilization methods

- Precise features for optical paths or fluidics

Both high-resolution 3D printing (e.g., SLA with biocompatible resins) and CNC machining of plastics or stainless steel are used, depending on quantity and regulatory requirements. CNC machining offers consistent surfaces and dimensional precision, while 3D printing allows rapid iteration of complex geometries for fluidic channels or integrated optical features.

Hybrid Approaches and Post-Processing Strategies

In many cases, an optimal solution combines 3D printing and CNC machining or uses post-processing to bridge gaps in capability.

3D Printing with Critical Surfaces Machined

One common approach is to 3D print the housing body and then machine critical surfaces such as:

- O-ring grooves and sealing faces

- Threaded connections

- Reference planes for PCB alignment

This enables complex internal structures while achieving high accuracy where needed. It is particularly relevant for SLS/MJF nylon parts and metal additive parts, which can be fixtured and machined after printing.

Use of Inserts, Gaskets, and Coatings

Performance of additively manufactured housings can be enhanced by incorporating:

- Metal inserts for threads, heat sinking, or mounting surfaces

- Standardized cable glands and connectors rather than directly printed threads

- Conformal coatings or metalized layers for EMI shielding

For CNC-machined housings, O-rings, flat gaskets, and sealants provide robust sealing even with moderate surface roughness, reducing the need for extremely fine surface finishes on all areas.

Stage-Based Use Across Product Lifecycle

A typical lifecycle strategy for custom sensor housings may include:

- Concept and early prototype: primarily 3D printing (FDM, SLA, or SLS)

- Functional testing and field trials: refined 3D-printed housings with limited machining, or directly CNC-machined housings for critical applications

- Low- to medium-volume production: CNC machining of metals or plastics, possibly with some 3D-printed ancillary components

This staged approach allows rapid learning in early development while ensuring robust performance in later production.

Decision Guidelines for Selecting 3D Printing or CNC Machining

Selecting between 3D printing and CNC machining for sensor housings can be organized around a few key technical criteria. While each project has unique constraints, the following guidelines summarize typical patterns.

When 3D Printing Is Generally Suitable

3D printing is usually appropriate when:

- Quantities are low and designs are likely to change (prototypes, early-stage projects)

- Complex internal geometries or integrated features are required that are difficult to machine

- Mechanical loads are modest and environmental exposure is moderate

- Rapid turnaround is more important than the tightest possible tolerances

For example, an indoor air quality sensor with a compact plastic housing and intricate airflow paths may be initially produced via SLA or SLS for evaluations, with attention to material stability and sealing for any later field deployment.

When CNC Machining Is Generally Suitable

CNC machining is typically favored when:

- High dimensional accuracy and stable sealing interfaces are required

- Housings must withstand high pressures, temperatures, or aggressive chemicals

- Metal housings are needed for structural or EMC reasons

- Quantities justify setup costs and benefit from repeatable production

Examples include stainless steel housings for pressure transmitters, aluminum enclosures for outdoor industrial gateways, or high-precision plastic housings for optical displacement sensors.

Balancing Requirements and Constraints

In real projects, constraints such as available equipment, supplier capabilities, regulatory requirements, and time-to-market also influence the choice. A structured decision often considers:

- Required IP rating and sealing strategy

- Operating temperature range and environmental exposure

- Mechanical load cases (shock, vibration, mounting stresses)

- Target production volume over product lifetime

- Budget allocation for development versus production tooling

By aligning these parameters with the capabilities of 3D printing and CNC machining, teams can select a manufacturing route that supports both technical performance and economic efficiency.

FAQ: Custom Sensor Housings, 3D Printing, and CNC

Which process is better for waterproof sensor housings?

For waterproof or high IP-rated sensor housings, CNC machining of metal or engineering plastic generally offers more reliable results. It provides better control over flatness, surface finish, and dimensional tolerances for sealing surfaces and O-ring grooves. 3D printing can be used for waterproof housings if suitable materials and processes are chosen (e.g., SLS/MJF with careful design) and if post-processing addresses surface porosity and warping. However, achieving consistent high IP ratings is typically more straightforward with CNC-machined housings.

Can 3D-printed sensor housings be used for long-term field deployment?

3D-printed sensor housings can be used in long-term deployments when appropriate materials, processes, and design practices are applied. For example, SLS/MJF nylon and certain engineering-grade SLA resins can provide sufficient strength and environmental resistance for many applications. Key considerations include UV stability, moisture absorption, thermal performance, and mechanical load paths. It is common to validate long-term suitability through environmental and endurance testing. For highly critical or harsh environments, CNC-machined metal or high-performance plastic housings are often preferred for greater safety margins and predictability.