Corrosion protection of metal parts is a critical engineering task that directly affects safety, reliability, lifecycle cost, and regulatory compliance. An effective corrosion control strategy combines correct material selection, protective coatings, surface treatments, design optimization, and suitable inspection and maintenance practices. This guide provides a systematic overview of corrosion mechanisms, influencing factors, protection methods, relevant standards, and testing approaches for a wide range of industrial applications.

Fundamentals of Corrosion in Metals

Corrosion is the deterioration of a metal due to chemical or electrochemical interaction with its environment. Understanding the fundamental mechanisms is essential to select adequate protection methods and predict service life.

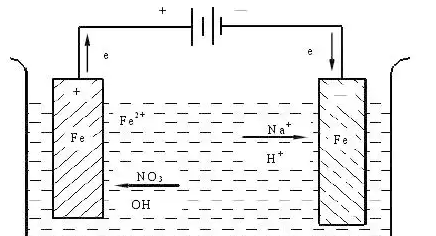

Electrochemical Principles

Most metallic corrosion in aqueous and atmospheric environments is electrochemical. Metal atoms lose electrons and become ions (anodic reaction), while a reduction reaction consumes electrons (cathodic reaction). For example, steel in an aerated electrolyte typically exhibits:

- Anodic reaction: Fe → Fe²⁺ + 2e⁻

- Cathodic reaction (in neutral aerated solution): O₂ + 2H₂O + 4e⁻ → 4OH⁻

- Formation of corrosion products: Fe²⁺ + 2OH⁻ → Fe(OH)₂, which can convert to rust (hydrated iron oxides)

These reactions occur on different locations of the metal surface, forming microscopic or macroscopic galvanic cells. Differences in composition, microstructure, stress, or environment generate potential differences that drive corrosion currents.

Common Corrosion Types in Metal Parts

Recognizing corrosion forms helps in selecting appropriate protection methods and inspection techniques.

- Uniform corrosion: Metal loss occurs fairly evenly over large areas. It is common on unprotected carbon steel and is relatively predictable.

- Galvanic corrosion: Occurs when two dissimilar metals are electrically connected in the same electrolyte, causing the more active metal to corrode preferentially.

- Pitting corrosion: Localized, highly penetrative attack producing small pits or cavities, frequently seen on stainless steels, aluminum, and copper alloys in chloride-containing environments.

- Crevice corrosion: Localized attack in shielded areas such as joints, under gaskets, deposits, or lap joints where the environment becomes stagnant and more aggressive.

- Intergranular corrosion: Attack along grain boundaries, usually associated with improper heat treatment or sensitization (e.g., chromium carbide precipitation in stainless steel).

- Stress corrosion cracking (SCC): Cracking driven by the combination of tensile stress and a specific corrosive environment. It can occur at stress levels below the yield strength.

- Erosion-corrosion: Accelerated attack due to relative motion between a corrosive fluid and the metal surface, often at high velocity or with solid particles present.

- Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC): Corrosion affected by microorganisms, such as sulfate-reducing bacteria, which alter local chemistry and electrochemistry.

Key Factors Influencing Corrosion of Metal Parts

Corrosion rate and morphology depend on multiple interacting factors. Quantifying and controlling them is fundamental for long-term protection.

Environmental Parameters

Important environmental variables include:

- Electrolyte composition: Presence of chlorides, sulfates, carbonates, nitrates, and other ions strongly affects corrosion rates. Chloride ions are particularly aggressive to many alloys.

- pH: Acidic (pH < 7) or alkaline (pH > 9) environments can significantly accelerate corrosion or influence passivity. For carbon steel, minimum corrosion is often near neutral pH in oxygen-poor environments.

- Oxygen availability: Oxygen is the most common oxidizing agent. Its concentration influences cathodic reaction rate and can promote differential aeration cells leading to localized corrosion.

- Temperature: Higher temperatures generally increase corrosion rate due to enhanced reaction kinetics and decreased oxygen solubility, but may also alter film stability and phase equilibria.

- Flow conditions: Stagnant conditions can produce crevice-like behavior, while high flow may remove protective films and corrosion products, leading to erosion-corrosion.

- Humidity and contaminants: In atmospheric corrosion, relative humidity above the critical humidity (often around 60–70% for chloride-contaminated surfaces) can form a persistent electrolyte layer. Industrial pollutants (SO₂, NOx) and sea salts increase aggressiveness.

Material Properties and Metallurgy

Intrinsic characteristics of the metal or alloy influence corrosion behavior:

- Chemical composition: Alloying elements (Cr, Ni, Mo, Cu, Si, Al) can promote passivation, increase corrosion resistance, or influence localized corrosion susceptibility.

- Microstructure: Grain size, phase distribution, inclusions, and segregation can cause local galvanic cells and susceptibility to intergranular corrosion.

- Heat treatment: Improper solution treatment or tempering can generate precipitates at grain boundaries, sensitization, or residual stresses, impacting SCC and intergranular attack.

- Surface condition: Roughness, machining marks, weld defects, and cold work increase surface area, create stress concentration sites, and may break protective films.

Design and Operational Conditions

Design and operation affect how the environment interacts with metal surfaces.

- Geometry: Sharp corners, dead zones, narrow gaps, blind holes, and overlapping joints favor stagnation and crevice conditions.

- Assembly and joints: Galvanic couples, dissimilar fasteners, and conductive gaskets can create galvanic corrosion. Welds can introduce local composition changes and residual stresses.

- Loads and vibration: Applied stresses influence SCC and fatigue-corrosion interaction, and may reduce effectiveness of certain coatings.

- Maintenance and cleaning: Inadequate cleaning leaves deposits that trap moisture and contaminants. Over-aggressive cleaning can damage protective layers.

Material Selection for Corrosion-Resistant Performance

Selecting appropriate materials is the first line of defense. Material choice should consider environmental conditions, expected lifetime, mechanical requirements, fabrication processes, and economic constraints.

Carbon Steels and Low-Alloy Steels

Carbon and low-alloy steels are widely used due to their mechanical properties and cost-effectiveness, but they are inherently susceptible to corrosion in most environments. Their use typically requires protective coatings, inhibitors, or cathodic protection, particularly in marine, industrial, or buried conditions.

Low-alloy steels with small additions of Cr, Cu, Ni, or Mo can provide improved atmospheric corrosion resistance (weathering steels), but they are not suitable as a universal substitute for coatings, especially in persistent wet or chloride-laden environments.

Stainless Steels

Stainless steels owe their corrosion resistance to a chromium-rich passive film. Chromium content of at least about 10.5% is required for stainless behavior, and higher contents improve resistance in many environments.

Common families include:

- Austenitic stainless steels (e.g., 304, 316): Good general corrosion resistance, excellent formability and weldability. Alloys with molybdenum (such as 316) exhibit improved resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion in chloride environments.

- Ferritic stainless steels: Lower nickel content, good resistance to stress corrosion cracking in many environments, but sometimes reduced toughness and weldability compared to austenitic grades.

- Duplex stainless steels: Mixed austenitic-ferritic microstructure with high yield strength and improved pitting and crevice corrosion resistance due to higher chromium, molybdenum, and nitrogen contents.

Selection among stainless steels often uses quantitative indices such as the Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number (PREN), which estimates resistance to localized corrosion in chloride-containing media.

Aluminum and Its Alloys

Aluminum forms a stable oxide layer that provides good corrosion resistance in many environments, especially neutral pH with limited chlorides. However, some aluminum alloys are prone to pitting and SCC in marine atmospheres and chloride solutions. Proper alloy selection, surface treatments (anodizing, conversion coatings), and isolation from more noble metals are important when aluminum parts operate in mixed-metal assemblies.

Copper, Nickel, and Other Alloys

Copper and copper alloys generally exhibit good resistance in non-oxidizing environments and drinking water systems but may experience dezincification (for brass) or erosion-corrosion in high-velocity fluids. Nickel-based alloys provide high resistance in strongly corrosive and high-temperature environments, including acid and high-chloride systems, but are more expensive. They are often reserved for critical components where failure has high safety or operational consequences.

Coating Systems for Corrosion Protection

Coatings act as physical barriers, sacrificial layers, or both. They are widely used because they can be tailored to specific environments and applied to many substrates. Performance depends on correct surface preparation, application method, film thickness, and adherence to specification.

Organic Paint and Powder Coatings

Organic coatings include liquid paints and powder coatings. They primarily provide barrier protection, isolating the metal from corrosive agents.

Key parameters and considerations include:

- Total dry film thickness (DFT): Often in the range of 60–300 µm depending on exposure category. Thicker multi-coat systems are used in severe marine or industrial environments.

- Coating system structure: Typically a primer (for adhesion and corrosion inhibition), intermediate coats (build layer, barrier), and topcoat (UV resistance, color, gloss).

- Resin type: Epoxy coatings offer excellent chemical resistance and adhesion but poor UV resistance. Polyurethane and polysiloxane topcoats provide UV stability and color retention for outdoor applications.

- Curing conditions: Ambient-cure systems must achieve full cure before exposure to severe environments. Heat-cure powder coatings require specific temperature-time cycles to reach designed performance.

Poor surface preparation (such as insufficient cleaning or incomplete rust removal) is a frequent cause of premature coating failure. Standardized surface preparation grades and cleanliness levels are often specified to minimize this risk.

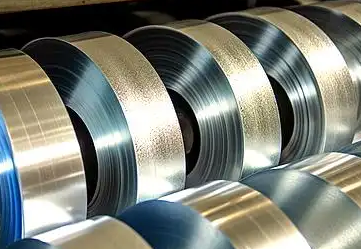

Metallic Coatings by Hot-Dip and Electroplating

Metallic coatings offer both barrier and often sacrificial protection. The most common are zinc-based systems for steel, but aluminum and other metals are also used.

Hot-dip galvanizing immerses steel components in molten zinc, forming a metallurgically bonded zinc-iron alloy layer with an outer zinc layer. Typical coating thickness values range from approximately 45 to more than 85 µm depending on steel thickness and process conditions. This approach provides long-lasting protection in many atmospheric and splash zone environments.

Electroplated coatings (zinc, nickel, chromium, tin, and others) are formed by passing current through an electrolyte bath. Electroplated zinc coatings are generally thinner than hot-dip layers but offer good sacrificial protection in many automotive, fastener, and hardware applications when combined with supplementary conversion and sealing layers.

Zinc-Rich Primers and Duplex Systems

Zinc-rich primers contain a high proportion of zinc dust in an organic or inorganic binder. When in electrical contact with the steel substrate, the zinc particles provide sacrificial protection, while the binder offers barrier properties. They are frequently used as the first coat in multi-layer systems for structures and equipment exposed to aggressive atmospheres.

Duplex systems combine galvanizing with organic coatings. The synergy between the zinc layer and the paint system significantly extends the service life compared to either protection alone. Duplex systems are common for bridges, towers, and poles in environments with high corrosion categories.

Surface Treatments and Chemical Conversion Layers

Surface treatments modify the metal surface to improve corrosion resistance, coating adhesion, or both. They are widely used for aluminum, magnesium, zinc, and some steels, especially in automotive, aerospace, and electronics applications.

Phosphate Coatings

Phosphate conversion coatings are formed by immersing steel or other metals in phosphate-containing solutions, producing a crystalline layer (such as zinc phosphate or manganese phosphate). They are commonly used as pretreatment before painting to improve adhesion and corrosion resistance. Typical coating weights for automotive-grade phosphate layers are often in the range of a few grams per square meter.

Chromate and Non-Chromate Conversion Coatings

Chromate conversion coatings are widely used on aluminum, zinc, and magnesium alloys for their excellent corrosion resistance and self-healing behavior. However, due to environmental and health concerns associated with hexavalent chromium, there is extensive use of trivalent chromate and other non-chromate technologies in many applications.

These conversion layers serve several functions:

- Provide initial corrosion protection.

- Promote adhesion of paints and sealants.

- Offer electrical conductivity where required (e.g., for electromagnetic shielding in electronics enclosures).

Anodizing

Anodizing is an electrochemical process that thickens the natural oxide layer on metals such as aluminum, titanium, and magnesium. On aluminum, sulfuric acid anodizing is widely used for architectural, aerospace, and consumer parts. The oxide layer thickness can range from a few micrometers for decorative or conductive applications to 25 µm or more for enhanced wear and corrosion resistance.

Porous anodic films can be sealed in hot water, steam, or specific solutions to close the pores and increase corrosion resistance. Dyeing treatments may be applied before sealing when color is required.

Cathodic Protection for Metal Structures

Cathodic protection (CP) is an electrochemical method that reduces the corrosion rate of a metal surface by making it the cathode of an electrochemical cell. It is widely applied to buried pipelines, tanks, offshore structures, ship hulls, and reinforced concrete.

Galvanic Anode Systems

In galvanic (sacrificial) anode CP, metals that are more active than the protected structure (such as magnesium, zinc, or aluminum alloys) are electrically connected to the structure in the presence of an electrolyte. The sacrificial anodes corrode instead of the structure.

Key elements for effective galvanic CP include:

- Selection of appropriate anode alloy with suitable driving potential and capacity for the environment.

- Correct sizing of anode mass and distribution to maintain protective potentials over the design life.

- Reliable electrical continuity within the structure to ensure uniform protection.

Impressed Current Cathodic Protection

Impressed current cathodic protection (ICCP) uses inert or semi-inert anodes (such as mixed metal oxide, silicon iron, or graphite) connected to a DC power source. The applied current is adjusted to maintain the required protection potentials.

Typical components include:

- DC power supply (rectifier or transformer-rectifier).

- Anode beds or distributed anodes in soil, water, or concrete.

- Reference electrodes for potential monitoring.

- Cabling and junction boxes to connect structure, anodes, and monitoring points.

ICCP offers greater control and flexibility for large or complex structures, but it requires monitoring, maintenance, and reliable power supply.

Design Considerations to Minimize Corrosion

Engineering design has a decisive impact on corrosion performance. Incorporating corrosion control measures at the design stage reduces the need for corrective actions and complex protection systems later.

Geometry and Drainage

Design principles to reduce moisture retention and contaminants include:

- Provide adequate slope and openings for drainage; avoid horizontal surfaces that accumulate water.

- Eliminate sharp corners and abrupt section changes that act as coating weak points and stress concentrators.

- Avoid narrow crevices, blind joints, and overlapped plates where possible. Where joints are necessary, use continuous welding instead of intermittent welds to reduce crevice formation.

- Ensure accessibility for cleaning, inspection, and recoating operations.

Galvanic Compatibility and Isolation

When different metals must be assembled in conductive environments, design measures should minimize galvanic corrosion:

- Choose metals with similar potential where feasible to reduce driving voltage.

- Isolate dissimilar metals using non-conductive gaskets, sleeves, washers, or coatings.

- Use protective coatings on the more noble metal or on both metals to reduce galvanic current.

- Increase the area of the more noble metal relative to the active one is generally unfavorable; the area ratio should be evaluated during design.

Welding, Brazing, and Joint Design

Welded and brazed joints can exhibit distinct corrosion behavior due to microstructural changes, residual stresses, and crevices. Recommended measures include:

- Select filler metals and procedures compatible with base materials and environment.

- Control heat input and post-weld heat treatment to minimize sensitization and residual stresses.

- Design welded joints to avoid pockets and crevices. Smooth transitions and continuous welds are preferable.

- Provide sufficient access for surface preparation and coating application across joints.

Cleaning, Surface Preparation, and Pretreatment

Correct preparation of metal surfaces before applying coatings or treatments is one of the most critical stages for reliable corrosion protection.

Removal of Contaminants

Surfaces must be free of oil, grease, salts, dust, and loose corrosion products. Common techniques are:

- Solvent cleaning: Organic solvents, aqueous detergents, or emulsions remove oils and organic contaminants.

- Alkaline cleaning: Alkaline solutions dissolve oils and form soaps, often followed by rinsing and neutralization.

- Pickling: Acid solutions remove mill scale and rust; inhibitors are frequently used to reduce base metal attack.

- High-pressure water jetting: Removes loose rust, coatings, and soluble salts, especially on large structures.

Surface Profile and Mechanical Preparation

The surface roughness and profile influence coating adhesion and mechanical interlocking. Mechanical preparation methods include abrasive blasting, power tool cleaning, and brushing.

Abrasive blasting parameters typically considered are:

- Abrasive type and hardness.

- Particle size distribution.

- Air pressure or wheel speed.

- Stand-off distance and angle of impact.

Resulting surface cleanliness and profile are often specified by standardized grades and roughness ranges appropriate for the coating system used.

Inhibitors and Controlled Environments

Corrosion inhibitors are chemicals that, when present in small concentrations in a corrosive environment, reduce the corrosion rate of a metal. Controlled environments include closed systems or storage conditions where humidity, oxygen, or contaminants are managed.

Types and Mechanisms of Corrosion Inhibitors

Corrosion inhibitors are commonly classified as:

- Anodic inhibitors: Promote the formation of protective oxide films, reducing anodic dissolution.

- Cathodic inhibitors: Reduce the rate of cathodic reactions, such as oxygen reduction or hydrogen evolution.

- Mixed inhibitors: Affect both anodic and cathodic processes.

- Volatile corrosion inhibitors (VCI): Sublime or evaporate to form a protective atmosphere within enclosed spaces, depositing on metal surfaces.

Proper inhibitor selection requires compatibility with the metal and environment, avoidance of unwanted deposits, and adherence to health, safety, and environmental regulations.

Environmental Control

Examples of environmental control include:

- Dehumidification of storage areas to maintain humidity below critical levels.

- Use of inert gas blanketing in tanks and process equipment to reduce oxygen availability.

- Filtration and purification of process fluids to remove corrosive species and solids.

Inspection, Testing, and Performance Evaluation

Verification of corrosion protection performance relies on inspection and testing methods. These methods are used during qualification of protection systems, quality control in production, and condition monitoring in service.

Visual and Non-Destructive Inspection

Visual inspection is the first and most frequently used method to detect coating defects, rust, blistering, cracking, or mechanical damage. It is often combined with simple tools such as magnifiers, mirrors, and thickness gauges.

Non-destructive testing (NDT) methods used in the context of corrosion protection include:

- Coating thickness measurement by magnetic, eddy-current, or ultrasonic instruments.

- Adhesion tests (pull-off tests, cross-cut) to evaluate bonding of coatings.

- Electrochemical tests, such as potential measurements on cathodically protected structures.

- Radiography, ultrasound, and other NDT techniques to detect internal corrosion or wall thinning.

Laboratory Corrosion Testing

Laboratory tests accelerate corrosion to compare materials or coatings and estimate relative performance. Common tests include:

- Salt spray (fog) tests using sodium chloride solutions to evaluate coatings and platings.

- Cyclic corrosion tests combining wet/dry cycles, salt spray, and temperature variations to simulate service environments more realistically.

- Electrochemical tests such as potentiodynamic polarization, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and linear polarization resistance (LPR) to characterize corrosion rates and protective film behavior.

Test method selection and interpretation require attention to the correlation between test conditions and actual service environments. Laboratory results provide comparative data but may not directly translate into absolute service life without additional field exposure data.

Standards, Specifications, and Compliance

Numerous international and national standards define procedures for corrosion protection, surface preparation, coating application, and testing. Applying standardized practices helps ensure consistent quality and facilitates communication between designers, manufacturers, applicators, and inspectors.

| Standard Category | Typical Content |

|---|---|

| Surface preparation and cleanliness | Definitions of rust grades, preparation grades, and methods for abrasive blasting, power tool cleaning, and measurement of surface profile. |

| Protective paint systems | Requirements for primers, intermediate coats, and topcoats; systems for specific environments; guidance on film thickness and application conditions. |

| Galvanizing and metallic coatings | Process requirements for hot-dip galvanizing, minimum coating thickness, adhesion criteria, and inspection procedures. |

| Cathodic protection | Design, installation, operation, and monitoring of CP systems for pipelines, tanks, offshore structures, and reinforced concrete. |

| Laboratory corrosion testing | Procedures for salt spray testing, cyclic corrosion tests, electrochemical measurements, and reporting of results. |

Project specifications usually reference particular standards and may add project-specific requirements such as minimum service life, maximum allowable defect size, test acceptance criteria, and detailed documentation needs.

Maintenance Strategies for Corrosion-Controlled Assets

Even well-designed corrosion protection systems require periodic assessment and maintenance to sustain performance throughout the intended service life.

Inspection Planning and Monitoring

Inspection intervals depend on criticality of components, environment severity, type of protection, and historical performance data. Common practices include:

- Routine visual inspections of exposed structures, focusing on edges, welds, drains, and fasteners.

- Scheduled coating thickness measurements and adhesion checks on representative areas.

- Regular potential and current measurements on cathodically protected systems.

- Corrosion coupons or probes in process lines to measure metal loss over time.

Repair and Rehabilitation

When deterioration is detected, appropriate repair measures are implemented:

- Localized coating repairs using compatible primers and topcoats after proper surface preparation.

- Replacement of sacrificial anodes approaching depletion, or adjustment of ICCP currents when structure potentials fall outside target ranges.

- Removal of corrosion products and deposits, followed by reapplication of protective systems.

- Structural repair or reinforcement when section loss exceeds acceptable limits, using corrosion-resistant materials or additional protection.

Comparison of Corrosion Protection Methods

Different corrosion protection strategies provide distinct balances of durability, cost, complexity, and suitability for specific environments. An integrated approach often combines multiple methods on the same component or structure.

| Protection Method | Main Mechanism | Typical Application Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Organic coating systems | Barrier protection, sometimes with active pigments | Structural steel, machinery, automotive bodies, equipment housings |

| Hot-dip galvanizing | Sacrificial metallic coating with barrier effect | Structural members, fasteners, poles, guardrails, lattice towers |

| Electroplated coatings | Barrier and sacrificial protection | Fasteners, small components, decorative hardware, connectors |

| Cathodic protection | Electrochemical potential control to suppress anodic dissolution | Pipelines, storage tanks, marine structures, ship hulls, reinforced concrete |

| Conversion and passivation treatments | Formation of protective films and coating adhesion promotion | Aluminum aircraft parts, automotive body panels, electronic enclosures |

| Material selection (stainless, nickel alloys) | Intrinsic corrosion resistance and passive film stability | Chemical process equipment, high-temperature service, critical components |

Typical Issues in Corrosion Protection of Metal Parts

Several recurring issues can compromise corrosion protection if not managed appropriately:

- Insufficient surface preparation: Residual contaminants or inadequate surface profile reduce coating adhesion and barrier effectiveness.

- Incorrect coating selection: Mismatch between coating system and environment can lead to rapid degradation, blistering, or underfilm corrosion.

- Galvanic coupling not considered: Neglected dissimilar metal contacts, especially in humid or marine conditions, can drive unexpected localized attack.

- Inadequate inspection and maintenance: Lack of periodic monitoring fails to detect early signs of deterioration, allowing minor defects to evolve into major damage.

- Uncontrolled process variations: Deviations in coating thickness, curing, or chemical treatment parameters reduce the performance margin of the protection system.

Integrated Approach to Corrosion Protection of Metal Parts

Effective corrosion protection is rarely achieved by a single measure. Instead, an integrated strategy is built from the following elements:

- Environmental characterization to understand exposure conditions and corrosion mechanisms.

- Material selection aligned with both mechanical and corrosion performance requirements.

- Appropriate combination of coatings, surface treatments, and cathodic protection where necessary.

- Design choices that minimize crevices, galvanic couples, and moisture traps.

- Well-defined surface preparation and application procedures, supported by training and quality control.

- Regular inspection, monitoring, and adaptive maintenance over the life of the asset.

When applied consistently, such a systematic approach ensures that metal parts achieve their intended service life with controlled corrosion-related degradation, contributing to reliability, safety, and cost-effective operation.

FAQ on Corrosion Protection of Metal Parts

What is the most effective way to protect steel parts from corrosion?

There is no single universally most effective method. The optimal protection for steel parts depends on the environment, required service life, geometry, and maintenance possibilities. In many atmospheric applications, a combination of high-quality surface preparation, a suitable multi-layer paint system, and, where appropriate, galvanizing (a duplex system) offers extended durability. For buried or submerged structures, cathodic protection combined with coatings is widely used. Material upgrades to more resistant alloys may be justified for critical components or particularly aggressive environments.

How important is surface preparation before applying an anti-corrosion coating?

Surface preparation is essential and often determines the success or failure of the entire corrosion protection system. Even a high-performance coating will perform poorly if applied on surfaces contaminated with oils, salts, loose rust, or mill scale. Proper cleaning, removal of corrosion products, and achieving a suitable surface profile are necessary to ensure adhesion, uniform film formation, and long-term barrier performance. Many coating failures can be traced back to inadequate or inconsistent surface preparation rather than the properties of the coating itself.

When is cathodic protection needed for metal components?

Cathodic protection is typically applied when metal components are continuously in contact with conductive environments such as soil, seawater, brackish water, or concrete with sufficient moisture. Examples include pipelines, underground storage tanks, offshore platforms, ship hulls, and reinforcing steel in concrete. It is especially beneficial when high reliability and long service life are required, and when coatings alone may be insufficient or difficult to maintain. Suitability and design of cathodic protection must be established through engineering analysis and relevant standards.

Can stainless steel corrode, and does it still need protection?

Stainless steel can corrode under certain conditions, especially in chloride-containing environments, acidic solutions, or when the passive film is damaged or locally broken. Forms of attack include pitting, crevice corrosion, and stress corrosion cracking. Protective measures may still be needed, such as selecting higher alloy grades with improved localized corrosion resistance, avoiding crevices in design, controlling temperature and chloride levels, and, in some cases, applying coatings or cathodic protection. Selection of stainless steel grade should be based on the specific environment and required service life.