Hard anodizing is one of the most widely used surface treatments for aluminum when very high wear resistance, corrosion protection, and dimensional stability are required. It is a controlled electrochemical conversion process that creates a thick, dense, ceramic-like oxide layer on aluminum and its alloys. This article explains the concept, the complete process flow, key parameters, performance characteristics, and the typical applications of hard anodized components in industrial environments.

Definition of Hard Anodizing

Hard anodizing, also called hardcoat anodizing or Type III anodizing (per MIL-A-8625 in the United States), is an electrolytic oxidation process that converts the surface of aluminum into a thick aluminum oxide (alumina) layer. Unlike a coating that is applied on top, the anodic layer is grown from the substrate itself. The resulting oxide is hard, wear resistant, and tightly adherent.

The term “hard” refers mainly to the high hardness and wear resistance of the oxide, which is considerably higher than that of conventional decorative anodizing (often referred to as Type II). Hard anodizing is typically performed in a sulfuric acid electrolyte at low temperatures with relatively high current density, producing a relatively thick and dense layer.

Key Characteristics of Hard Anodized Coatings

Hard anodized coatings are defined by a series of measurable physical and functional properties. Understanding these characteristics is essential when designing components and specifying process parameters.

| Property | Typical Range / Description |

|---|---|

| Coating thickness | 25–75 μm (0.001–0.003 in) commonly; up to ~150 μm in special cases |

| Hardness (microhardness) | ~350–600 HV (approx. 35–65 HRC), depending on alloy and process |

| Wear resistance | Substantially higher than bare aluminum and standard anodizing; suitable for sliding and abrasive contact |

| Coefficient of friction | Dry: generally higher than bare aluminum; can be reduced with lubrication or PTFE impregnation |

| Corrosion resistance | Excellent in many atmospheric and mild chemical environments, especially when sealed |

| Color | Typically dark gray to black; influenced by alloy composition and thickness |

| Dimensional change | Approx. 50% of thickness grows above original surface, 50% penetrates into substrate |

| Electrical properties | Good electrical insulation; dielectric strength depends on thickness and sealing |

| Thermal stability | Good up to several hundred degrees Celsius; excessive heat can affect sealing and color |

How Hard Anodizing Differs from Conventional Anodizing

Although hard anodizing and conventional sulfuric acid anodizing share the same basic electrochemical principle, they differ in process conditions and performance. These differences impact cost, appearance, and functional suitability.

- Hard anodizing uses lower bath temperature (often close to 0 °C) and higher current density than standard anodizing.

- The resulting layer is thicker, denser, and harder, with significantly better wear resistance and improved load-bearing capacity.

- Color is generally darker (gray to black), often limiting the range of dye colors compared with decorative anodizing.

- Dimensional change is greater and must be considered during precision machining and tolerance setting.

- Electrical insulation is higher due to greater thickness and density of the oxide.

Typical Aluminum Alloys Suitable for Hard Anodizing

Most wrought and cast aluminum alloys can be hard anodized, but alloy composition strongly influences achievable hardness, appearance, and uniformity.

| Alloy series / example | General suitability | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1xxx (pure Al) | Good | Produces clear to light gray coatings; lower hardness but excellent corrosion resistance. |

| 2xxx (Al-Cu, e.g., 2024) | Moderate | Copper reduces corrosion resistance and may lead to darker, less uniform coatings. |

| 3xxx (Al-Mn) | Good | Usually uniform coatings; used when moderate strength and good corrosion behavior are needed. |

| 5xxx (Al-Mg, e.g., 5052, 5083) | Good | Often anodize well with relatively light to medium gray color and good corrosion resistance. |

| 6xxx (Al-Mg-Si, e.g., 6061) | Very common | Widely used for hard anodized parts; good balance of hardness, strength, and anodizing quality. |

| 7xxx (Al-Zn-Mg, e.g., 7075) | Variable | High-strength series; can form hard coatings but may exhibit non-uniform color and microcracking if not properly controlled. |

| Cast aluminum alloys | Variable | High silicon or copper content can cause dark, patchy coatings and reduced thickness in silicon-rich regions. |

Complete Hard Anodizing Process Flow

The hard anodizing process consists of several ordered steps, from incoming inspection to final sealing and quality control. Process details vary among facilities, but the general sequence is similar.

1) Pre-cleaning and Surface Preparation

Proper preparation ensures uniform coating growth and strong adhesion.

Typical preparatory steps include:

- Degreasing or alkaline cleaning to remove oils, coolants, and organic contaminants.

- Rinsing in water to eliminate cleaner residues.

- Mechanical finishing such as sanding, grinding, blasting, or polishing (if specified) to impart the required surface roughness.

- Chemical etching (optional) in alkaline solutions to remove the native oxide and equalize minor surface defects.

- Desmutting in acidic solutions to remove intermetallic particles or smut left after etching.

The condition of the surface at this stage strongly affects the final appearance and roughness of the hard anodized layer.

2) Masking and Fixturing

Regions where the oxide should not form or where tight tolerances exist may need masking. Typical masking materials include specialized tapes, lacquers, or mechanical plugs made from compatible polymers. Proper fixturing is critical because it must:

- Ensure reliable electrical contact for current flow.

- Support the part without causing marks in critical zones.

- Allow adequate solution circulation and gas release around the component.

3) Hard Anodizing Electrolyte Bath

Most hard anodizing lines use a sulfuric acid-based electrolyte with controlled additions of water and sometimes organic additives or other acids. Typical bath parameters (ranges are indicative and adjusted by each facility) include:

- Sulfuric acid concentration: roughly 150–250 g/L.

- Temperature: often between about -5 °C and +5 °C for hard anodizing.

- Agitation: air or mechanical agitation to maintain uniform temperature and composition.

- Electrical power: direct current with controlled voltage and current density.

4) Electrical Parameters and Current Density Control

Current density and voltage are key variables for coating thickness, hardness, and microstructure. Common features of hard anodizing power control include:

- Higher current densities than decorative anodizing, typically in the range of about 2–5 A/dm², although exact values depend on alloy and facility capability.

- Voltage increases during the process as the oxide layer grows and electrical resistance rises.

- Time in the bath is adjusted to achieve the desired thickness, often ranging from several minutes to more than an hour for thick layers.

Cooling capacity and bath agitation must be sufficient to remove the heat generated by the high current and to keep the substrate temperature within the required range. If the workpiece overheats, the coating can burn, soften, or become powdery.

5) Coating Growth and Structure

The anodic film consists of a thin barrier layer at the metal interface and a thicker porous layer above it. In hard anodizing, the porous layer is relatively fine and dense compared with conventional anodizing. An important characteristic is that approximately half of the total coating thickness is formed above the original surface and half grows into the substrate. For example, a 50 μm coating typically causes about 25 μm build-up on the diameter and 25 μm penetration into the base metal.

The internal structure and porosity are influenced by alloy composition, electrolyte chemistry, temperature, and current density. The resulting microstructure determines hardness, wear resistance, and the capacity to accept impregnants such as PTFE or lubricants.

6) Rinsing After Anodizing

Immediately after the anodizing step, parts are thoroughly rinsed to remove acid residues from the pores and surfaces. Multiple rinses in cold water are commonly used, sometimes with conductivity control to ensure removal of residual electrolyte that could otherwise impair sealing or cause staining.

7) Optional Impregnation and Lubrication

Before sealing, some hard anodized parts are impregnated with secondary materials to modify friction and wear behavior. Examples include:

- PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene) or other fluoropolymers to reduce the coefficient of friction and enhance sliding performance.

- Dry film lubricants for applications where liquid lubricants are not acceptable or are difficult to maintain.

- Oils or waxes to improve corrosion protection or provide temporary lubrication.

Impregnation steps must be carefully controlled so they do not excessively alter dimensions or cause contamination in critical assemblies.

8) Sealing of Hard Anodized Coatings

Sealing closes or partially closes the pores of the anodic layer, thereby improving corrosion resistance and affecting dye fastness (if the coating has been colored). For hard anodizing, sealing options include:

- Hot deionized water sealing, where hydration of the oxide partially closes pores.

- Nickel acetate or other chemical sealing solutions for enhanced corrosion protection.

- Mid-temperature and cold sealing chemistries, depending on production requirements.

In some wear-critical applications, coatings may be left unsealed or only partially sealed to maintain higher hardness and better integral lubrication retention. The choice between sealed and unsealed treatments depends on the balance required between corrosion resistance and wear characteristics.

9) Drying, Demasking, and Final Finishing

After sealing, parts are dried by air, warm air, or controlled ovens. Masking materials and temporary plugs are removed, followed by inspection for residues or damage. If needed, minor post-process operations such as:

- Light polishing of non-functional surfaces.

- Application of additional lubricants or preservatives.

may be performed to achieve the specified final condition.

10) Inspection and Quality Control

Quality control in hard anodizing typically covers:

- Coating thickness measurement (e.g., eddy current, magnetic induction for suitable substrates, or cross-section microscopy).

- Hardness testing (microhardness on metallographic cross-sections).

- Wear testing (abrasion tests or application-specific tribological tests where required).

- Corrosion testing (e.g., salt spray according to relevant standards, when specified).

- Adhesion evaluation and visual inspection for burning, pitting, discoloration, or non-uniform coverage.

Main Benefits and Technical Advantages

Hard anodizing is widely used because it combines several functional benefits in a single integrated oxide layer. The main advantages include:

- High surface hardness and wear resistance suitable for sliding pairs, abrasive environments, and frequent mechanical contact.

- Excellent adhesion since the oxide is grown from the substrate and cannot easily delaminate.

- Good corrosion resistance in many industrial and outdoor environments, especially when sealed.

- Good dimensional control compared with many organic or thermal spray coatings because growth is predictable and the coating is relatively thin.

- Improved electrical insulation for components that must resist voltage or prevent short circuits.

- Enhanced heat dissipation for certain designs due to increased surface area and stable oxide behavior at elevated temperatures.

Design and Dimensional Considerations

When designing parts to be hard anodized, it is important to plan for coating thickness, dimensional change, and geometric effects. Key considerations include:

- Allowance for build-up: because about half of the layer thickness grows above the original surface, critical diameters and fits must account for this growth. Designers often reduce machining dimensions accordingly.

- Uniformity on edges and corners: electric field concentration leads to greater coating thickness at sharp edges and corners. Chamfers or radii help distribute current more evenly and reduce localized burning.

- Internal features: deep recesses, blind holes, and narrow gaps may experience reduced coating thickness or more difficult electrolyte circulation. This can affect wear and corrosion performance in these regions.

- Surface finish: the anodic layer replicates the underlying surface texture, and in many cases, it slightly increases roughness. Parts that require low friction or low roughness may need a smoother pre-machined finish before anodizing or additional finishing steps afterward.

- Threaded features: threads can be hard anodized but may experience reduced clearance, tighter fit, or increased risk of galling; thread allowances or masking may be necessary depending on functional requirements.

Typical Pain Points and Limitations in Practice

Despite its advantages, hard anodizing involves some practical limitations that must be considered in engineering and manufacturing:

- Color control: the natural color of hard anodized layers is strongly influenced by alloy composition and thickness, often resulting in dark gray to black hues with limited ability to achieve consistent decorative colors.

- Alloy sensitivity: high-copper or high-silicon alloys can lead to non-uniform or porous coatings with reduced performance, limiting material selection in some designs.

- Distortion risk: for thin or highly machined parts, exposure to low temperatures and electrochemical stress can lead to distortion or residual stress, especially if fixturing is inadequate.

- Dimensional tolerance management: tight tolerances on precision components may require careful pre-calculation of build-up, matched machining and anodizing process capability, and sometimes selective masking of critical dimensions.

- Repair and rework: the oxide layer is difficult to remove without attacking the base aluminum (e.g., in caustic stripping), which can change dimensions and geometry, making rework more complex than simply recoating.

Comparison with Other Surface Treatments on Aluminum

Engineers often compare hard anodizing with alternative treatments to meet specific requirements. Some common alternatives and relative characteristics include:

- Decorative anodizing: lower thickness and hardness, primarily for aesthetics and moderate corrosion protection; less suitable for highly loaded wear surfaces.

- Hard chrome plating on aluminum (with intermediate layers): can offer high hardness and low friction but involves additional process steps, different environmental considerations, and different adhesion characteristics.

- Thermal spray coatings: can provide very thick, extremely hard layers but often require more machining allowance and may not be suitable for very small or intricate parts.

- Organic coatings (paints, powder coatings): provide color, corrosion protection, and electrical insulation but are not usually equivalent to hard anodizing in wear resistance or hardness.

Typical Industrial Applications of Hard Anodizing

Hard anodizing is widely used wherever aluminum must withstand mechanical wear, friction, and environmental exposure while preserving low weight and good mechanical properties.

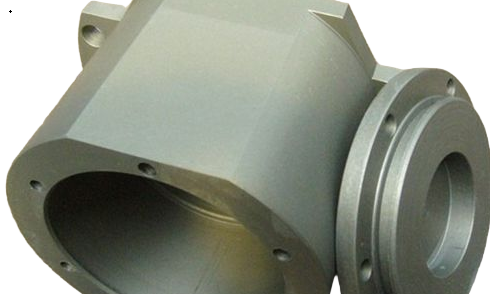

Aerospace and Defense Components

Hard anodizing is common in aerospace and defense sectors due to the combination of light weight and durability. Typical applications include:

- Landing gear components and guiding elements where sliding and impact occur.

- Actuator housings, valve bodies, and hydraulic manifolds requiring wear resistance and corrosion protection.

- Structural fittings, brackets, and connectors exposed to cyclic loads and outdoor conditions.

- Military firearm components, such as receivers and rails, to improve wear resistance and reduce maintenance frequency.

Automotive and Transportation

In automotive and other vehicles, weight reduction and durability are important. Hard anodized aluminum parts are used in:

- Suspension and steering components where metal-to-metal contact or abrasive particles are present.

- Pneumatic and hydraulic system parts such as cylinders, pistons, and valve bodies.

- High-performance engines and driveline components that require both strength and wear resistance.

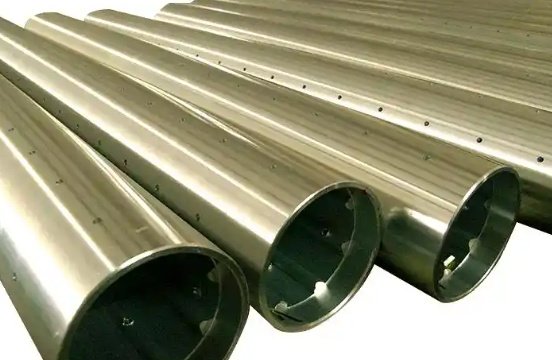

Mechanical Engineering, Machinery, and Automation

Industrial machinery often includes hard anodized aluminum parts to reduce wear while maintaining low mass and good machinability. Example applications:

- Guide rails, linear motion components, and bearing surfaces subject to repetitive sliding.

- Pneumatic cylinder tubes and pistons that must withstand repeated motion and pressure cycles.

- Robotic arms, fixtures, and frames requiring scratch resistance and dimensional stability.

- Pump housings, impellers, and other parts exposed to fluid flow and potential particle abrasion.

Electronics, Electrical, and Thermal Management

Because the anodic layer is electrically insulating yet thermally stable, hard anodizing is used in electrical and electronic equipment such as:

- Housings and enclosures requiring electrical isolation and environmental protection.

- Heat sinks and thermal management structures where surface protection and controlled emissivity are needed.

- Mounting plates and chassis that must provide insulation between conductive components.

Food Processing, Medical, and General Industrial Equipment

Hard anodized aluminum components are also found in sectors where hygiene, corrosion resistance, and surface durability are critical:

- Food processing machinery parts such as mixer blades, conveyor components, and wear strips where cleaning is frequent.

- Medical and laboratory equipment frames, fixtures, and housings that require frequent disinfection.

- Industrial tooling, jigs, and fixtures used in high-volume manufacturing environments.

Process Control and Specification Standards

To ensure reproducible performance, hard anodizing is often performed according to recognized standards and customer specifications. Common standards include, for example:

- MIL-A-8625 (or its successors), particularly Type III for hard anodic coatings on aluminum and aluminum alloys.

- ISO, ASTM, and other regional or industry-specific standards for anodic oxidation of aluminum.

Technical drawings typically specify:

- Required coating thickness or range.

- Sealed or unsealed condition, and any particular sealing method if critical.

- Allowed color or appearance range, where relevant.

- Areas to be masked or exempt from treatment.

- Any special test requirements such as hardness, corrosion resistance, or wear performance.

Maintenance and Service Life of Hard Anodized Parts

The service life of hard anodized components depends on operating conditions, load, lubrication, and environment. In many applications, the hard anodic layer provides long-term protection with limited maintenance needs. Some general points include:

- Regular cleaning to remove abrasive contaminants extends the life of sliding surfaces.

- Use of compatible lubricants can significantly reduce wear and prevent galling.

- Avoidance of strong alkaline cleaners or highly aggressive chemicals helps preserve the integrity of the oxide layer and any sealing treatment.

- Inspection intervals are determined based on criticality of the component and operating severity; worn coatings can sometimes be stripped and re-anodized if dimensional allowances permit.

Safety and Environmental Considerations (Process Perspective)

The hard anodizing process involves handling of acids, electrical power, and low-temperature baths. From a process management perspective, key aspects typically addressed in manufacturing environments include:

- Proper ventilation and handling procedures for acid mist and fumes in the anodizing area.

- Electrical safety measures for high-current DC rectifiers and bus bars.

- Temperature control of baths to avoid overheating or freezing conditions.

- Rinse water treatment and waste management to comply with local environmental regulations.

These aspects are normally handled by the processing facility but can influence production cost, facility layout, and subcontracting choices.

Summary

Hard anodizing is a robust and well-established method for enhancing the surface performance of aluminum and its alloys. By creating a thick, dense aluminum oxide layer, it combines high hardness, wear resistance, corrosion protection, and electrical insulation while preserving the core benefits of aluminum such as low weight and ease of machining. With proper design allowances, alloy selection, and process control, hard anodized components can deliver reliable service in demanding sectors including aerospace, automotive, industrial machinery, electronics, and food processing.

FAQ About Hard Anodizing

What is hard anodizing?

Hard anodizing is an electrochemical process that creates a thick, hard, and wear-resistant oxide layer on the surface of aluminum or aluminum alloys, improving durability, corrosion resistance, and surface hardness.

How is hard anodizing different from regular anodizing?

Compared to standard anodizing, hard anodizing produces a much thicker oxide layer (typically 25–150 µm), higher hardness (up to 60–70 HRC equivalent), and better wear and abrasion resistance.

What is the hard anodizing process?

The process involves immersing aluminum in a sulfuric acid electrolyte and applying a controlled electrical current, which converts the surface into a dense, hard aluminum oxide layer. The part is often cooled to maintain optimal hardness.

What are the benefits of hard anodizing?

Benefits include enhanced surface hardness, improved wear resistance, corrosion protection, low friction, electrical insulation, and longer service life.

Can hard anodized parts be machined after anodizing?

It is difficult because the anodized layer is very hard. Most machining is done before anodizing, and only light finishing or minor adjustments are possible afterward.