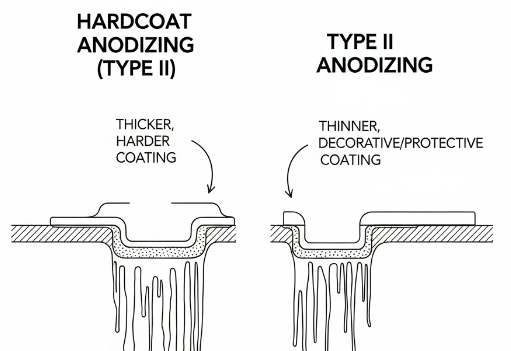

Anodizing is a widely used electrochemical process that converts the outer layer of aluminum into a durable, corrosion-resistant oxide. Among the standard anodizing categories, hardcoat anodizing (commonly referred to as Type III) and Type II sulfuric acid anodizing are the most frequently compared. Understanding their technical differences is essential for selecting the correct finish for performance, cost, and appearance requirements.

Overview of Anodizing Types

Both hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing are based on the sulfuric acid process defined in standards such as MIL-A-8625 and its successors. The key distinction lies in operating conditions and resulting coating characteristics.

In general terminology:

- Type II anodizing: Conventional sulfuric acid anodizing, typically used for decorative and general-purpose protective finishes.

- Hardcoat anodizing (Type III): Heavy-duty sulfuric acid anodizing with increased thickness and hardness for demanding wear and corrosion conditions.

While the base chemistry is similar, variations in temperature, current density, and time lead to significantly different coating structures and properties.

Process Fundamentals

Anodizing uses an electrolytic cell where aluminum acts as the anode in an acidic bath. When current passes through the solution, oxygen is released at the surface and reacts with aluminum to form aluminum oxide. The film grows both inward into the substrate and outward above the original surface.

Typical process elements include:

- Workpiece: Aluminum alloy component, electrically connected as the anode.

- Electrolyte: Sulfuric acid solution with controlled concentration and temperature.

- Power supply: Provides direct current at specified current density and voltage.

- Cathodes: Usually aluminum or lead, arranged around the workpiece.

The specific operating window defines whether the coating qualifies as Type II or hardcoat.

Key Differences Between Hardcoat and Type II Anodizing

Hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing differ primarily in thickness, hardness, wear resistance, and process parameters. The table below summarizes their main technical distinctions.

| Parameter | Hardcoat Anodizing (Type III) | Type II Sulfuric Anodizing |

|---|---|---|

| Typical coating thickness | 1.0–4.0 mil (25–100 µm), common range 1.0–2.5 mil | 0.2–1.0 mil (5–25 µm), common range 0.2–0.8 mil |

| Hardness (approx.) | ~ 400–600+ HV (Vickers), depending on alloy and process | ~ 250–400 HV (Vickers), depending on alloy and dye/seal |

| Bath temperature | Low temperature, typically around –5 to +5 °C (23–41 °F) | Moderate temperature, typically around 18–24 °C (64–75 °F) |

| Current density | High, often around 24–37 A/ft² (2.5–4 A/dm²) or higher | Moderate, often around 12–24 A/ft² (1.2–2.5 A/dm²) |

| Color (as anodized) | Dark gray to nearly black on many alloys | Clear to slightly gray, can be easily dyed to many colors |

| Wear resistance | Very high, suitable for sliding and abrasive contact | Moderate, suitable for general protection, not heavy wear |

| Dimensional impact | Significant, usually 50% growth above original surface | Lower impact, easier to accommodate in tight tolerances |

| Primary use | Functional, industrial, and military components | Decorative, architectural, and general-purpose parts |

Process Parameters and Operating Conditions

The performance of anodized coatings is strongly linked to the process conditions. Hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing use similar materials but different operating windows.

Electrolyte Composition

Both processes commonly use sulfuric acid electrolyte with typical concentrations in the approximate range of 150–220 g/L (about 15–22 wt% H₂SO₄). Hardcoat baths may employ more stringent control of sulfate, dissolved aluminum, and contaminants due to the higher current densities and targeted coating properties. Additives may be used to modify pore structure, reduce burning, or enhance throwing power, but the fundamental chemistry remains sulfuric acid based.

Temperature Control

Temperature is a critical differentiator:

- Hardcoat anodizing: Operated at low temperatures, typically below 5 °C, to minimize dissolution of the forming oxide and allow thick, dense coatings to build. This requires refrigeration and tight control to keep bath temperature in a narrow range.

- Type II anodizing: Operated at 18–24 °C, where formation and dissolution of oxide are more balanced, resulting in thinner, more porous films suitable for dyeing and sealing.

Current Density and Time

Hardcoat anodizing uses significantly higher current density and often longer cycle times:

- Hardcoat: High current density, frequently 2.5–4 A/dm², applied for sufficient time to produce 25–100 µm coatings. Process control is important to avoid burning and to maintain uniform thickness on complex geometries.

- Type II: Moderate current density around 1.2–2.5 A/dm², with shorter anodizing times that produce thin films ideal for decorative applications.

Voltage typically rises during the cycle as the oxide grows and electrical resistance increases. Power supplies must be capable of delivering the required current at higher voltages without excessive ripple.

Coating Structure and Thickness

The oxide layer produced by anodizing has a characteristic structure composed of a thin barrier layer at the metal interface and a thicker porous layer above it. The balance of pore size, porosity, and thickness influences hardness, color, and dye uptake.

Growth Ratio and Dimensional Change

Anodic oxide forms partly by converting aluminum beneath the surface and partly by building outward. A typical rule of thumb is that approximately 50% of the coating thickness grows outward and 50% inward, although this ratio can vary with alloy and process.

For design purposes:

- A 50 µm hardcoat layer may add about 25 µm to the external dimension, while consuming about 25 µm of the original aluminum surface.

- A 10 µm Type II coating may add about 5 µm to the dimension and consume 5 µm of metal.

This dimensional growth is critical where tight fits, threads, or precision sealing surfaces are involved. Hardcoat, with its higher thickness, requires more careful dimensional allowance in the design and machining stages.

Thickness Ranges and Control

Typical practical thickness ranges include:

- Hardcoat anodizing: Commonly 25–50 µm for many industrial applications; can be extended up to about 75–100 µm where necessary and where alloy and geometry permit.

- Type II anodizing: Frequently 5–25 µm, with 10–15 µm being common for decorative and corrosion-resistant purposes.

Thickness is normally measured using eddy current instruments or destructive cross-section methods. Uniformity depends on part geometry, alloy composition, agitation, racking, and electrical contact. Thin Type II coatings tend to be more uniform on complex shapes, while thick hardcoats may show greater variation between edges and recessed areas.

Hardness and Wear Resistance

One of the main reasons to select hardcoat anodizing is its high hardness and wear resistance compared to Type II coatings.

Hardness Values

The anodic aluminum oxide formed in hardcoat anodizing is dense and closely packed, resulting in hardness similar to many ceramics. Typical approximate hardness values:

- Hardcoat anodizing: Around 400–600+ HV, depending on alloy, bath chemistry, and thickness.

- Type II anodizing: Around 250–400 HV, which is harder than most untreated aluminum alloys but lower than hardcoat levels.

Hardness can vary through the thickness of the film and between alloys. Certain high-silicon or high-copper alloys may produce coatings of different hardness and consistency compared to more anodizing-friendly alloys such as 5000 or 6000 series.

Wear and Abrasion Performance

High hardness translates into improved wear resistance in many applications, particularly where surfaces experience sliding contact, light abrasive loading, or repeated assembly and disassembly. Hardcoat anodizing is widely used for:

- Pneumatic and hydraulic components.

- Valve bodies and spools.

- Sliding guides, pistons, and cylinders.

- Tooling, jigs, and fixtures subject to repeated handling.

Type II anodizing provides adequate abrasion resistance for everyday use on consumer products, housings, and furniture, but it is not intended for heavy-duty wear conditions. Where friction and load are critical, hardcoat is generally preferred, often combined with lubrication such as PTFE impregnation or oil to further reduce friction and extend service life.

Corrosion Resistance and Environmental Performance

Both hardcoat and Type II anodizing improve corrosion resistance by creating a stable oxide barrier on aluminum. However, the degree of protection depends on coating thickness, sealing, and environment.

Corrosion Protection Mechanisms

The anodic oxide is chemically bonded to the aluminum substrate and resists many corrosive media. The porous structure can absorb contaminants and water unless sealed, so most applications require a subsequent sealing step. Sealed anodic coatings offer improved resistance to:

- Atmospheric corrosion and moisture.

- Many neutral aqueous environments.

- Some mild chemical exposures, depending on pH and temperature.

Hardcoat’s greater thickness provides a longer diffusion path and more barrier material between the environment and substrate. Even if minor surface damage occurs, the underlying layer can still offer protection.

Sealing Practices

Sealing closes the pores of the oxide and improves corrosion resistance but may slightly reduce hardness and wear properties. Common sealing methods include:

- Hot deionized water sealing (hydration of the oxide).

- Nickel acetate sealing.

- Other proprietary sealing chemistries.

Type II coatings are very commonly sealed, especially when dyed, to lock in color and enhance corrosion resistance. Hardcoat may be left unsealed for maximum hardness and wear, or lightly sealed depending on the balance between wear and corrosion requirements. For applications with both high wear and corrosion demands, process parameters are optimized to maintain adequate hardness while achieving sufficient sealing performance.

Color, Dyeing, and Aesthetics

Aesthetic requirements often drive the choice between Type II anodizing and hardcoat anodizing, particularly in consumer-facing products.

Natural Color and Appearance

Type II anodizing in its natural, undyed state generally appears clear to slightly gray, allowing the metallic appearance of the aluminum to show through. Surface finish prior to anodizing (e.g., polished, brushed, bead blasted) strongly influences the final look.

Hardcoat anodizing, due to its greater thickness and dense microstructure, tends to produce darker shades ranging from medium gray to dark gray or nearly black, depending on the alloy and thickness. Reflectivity is usually lower, leading to a more matte appearance.

Dyeing Capability

Type II anodic films have relatively large pores that readily accept dyes, making them suitable for a broad range of colors including black, blue, red, gold, and others. Decorative anodizing relies on controlled pore structure and consistent thickness to achieve uniform color.

Hardcoat anodizing can be dyed, but its darker natural appearance and smaller pore volume limit the range and brightness of achievable colors. Black is the most common dyed color for hardcoat. Where vivid colors are required, Type II anodizing is generally preferred.

Substrate Alloys and Their Influence

Aluminum alloy composition significantly affects anodizing behavior and resulting coating quality for both hardcoat and Type II processes.

Alloy Categories

Broadly, the main alloy groups include:

- 1xxx series (commercially pure aluminum) – excellent anodizing response, very uniform coatings.

- 5xxx series (Al-Mg) – generally good for both Type II and hardcoat, with good corrosion performance.

- 6xxx series (Al-Mg-Si) – widely used, reasonable anodizing quality, good combination of properties.

- 2xxx and 7xxx series (Al-Cu and Al-Zn-Mg) – higher strength but can be more challenging; coatings may have reduced corrosion resistance or more pronounced color variation.

- High Si or cast alloys – may result in mottled appearance and somewhat different hardness or porosity.

For hardcoat anodizing, alloy selection is especially important because high currents and extended times tend to highlight alloy-related differences in coating uniformity and microstructure.

Design and Dimensional Considerations

Hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing affect part dimensions and tolerances differently due to their respective thicknesses and growth behavior. Careful allowance in the design phase helps avoid assembly issues and functional problems.

Dimensional Allowances

Because roughly half the oxide thickness builds outward, external features become larger and internal features become smaller after anodizing. Designers should consider:

- Critical diameters: For hardcoat, dimension changes can be in the range of 50 µm or more, which must be considered for precision fits and sliding interfaces.

- Threads: Coating buildup on both internal and external threads can affect fit class and torque; thread dimensions or after-anodize chasing may be needed.

- Sharp corners: High current density at edges can lead to increased thickness and potential burning, especially in hardcoat; radiusing edges can improve uniformity.

For Type II anodizing, the impact is smaller but still relevant for very tight tolerances or miniature components.

Masking and Selective Anodizing

In some cases, only part of the surface should be anodized, or certain areas must remain conductive for electrical or mechanical reasons. Masking techniques include tapes, paints, and fixtures that protect selected surfaces from the electrolyte. Hardcoat anodizing may require more robust masking due to the longer process and higher currents. Mask design should account for electrolyte flow and potential masking material degradation.

Mechanical and Functional Performance

Beyond hardness and corrosion resistance, both anodizing types influence other mechanical and functional aspects such as fatigue, friction, and adhesion.

Fatigue Considerations

Like many surface treatments that create a hard, brittle outer layer, anodizing can influence fatigue performance. The presence of a relatively stiff oxide layer and surface microcracks can act as initiation sites in cyclic loading. Thick hardcoat layers may have a more pronounced impact on fatigue strength compared with thin Type II coatings. For components subject to high-cycle fatigue, designers often balance the need for surface protection with potential fatigue life reduction, sometimes adjusting coating thickness or avoiding anodizing in highly stressed regions.

Friction and Lubricity

As-formed anodic oxide has relatively high surface friction, especially in dry sliding conditions. Hardcoat anodizing can be modified to improve lubricity by:

- Impregnating pores with PTFE or other solid lubricants.

- Applying compatible liquid lubricants after anodizing.

Type II coatings used primarily for appearance or corrosion protection may not require special friction management, but for moving assemblies, attention to lubrication and counter-surface material can be important.

Applications of Hardcoat Anodizing

Hardcoat anodizing is selected when components must withstand significant wear, abrasion, or demanding environments while maintaining the advantages of lightweight aluminum. Typical application categories include:

Mechanical and Industrial Components

- Pistons, cylinders, and actuator rods.

- Sliding bushings and guides.

- Gears, cams, and rotating mechanisms.

- Tooling components, clamps, and fixtures subject to repeated use.

Defense, Aerospace, and Transport

- Weapon system components, rails, and mounts.

- Aircraft interior and structural parts needing wear resistance without significant weight increase.

- Landing gear bushings and actuator housings.

Fluid Handling and Valves

- Valve bodies and spools exposed to fluid flow and particulate matter.

- Pump components subject to erosion and cavitation effects.

In many of these applications, hardcoat may be paired with tight dimensional control, selective masking, and lubricants to achieve reliable long-term performance.

Applications of Type II Anodizing

Type II anodizing is widely used wherever a balance of appearance, corrosion resistance, and moderate surface hardness is required.

Consumer and Electronic Products

- Housings for consumer electronics, laptops, and mobile devices.

- Appliance panels, knobs, and trim.

- Sporting goods and recreational equipment components.

Architectural and Interior Elements

- Window frames, door frames, and curtain wall elements.

- Interior design profiles, handle hardware, and decorative panels.

- Furniture components requiring colored and aesthetically stable finishes.

General Industrial Usage

- Machine covers, brackets, and enclosures.

- Optical and instrumentation housings.

- Components where identification by color is important.

Type II anodizing’s ability to accept a wide range of dyes and finishes while maintaining corrosion resistance makes it suitable for both functional and decorative roles.

Cost, Production, and Process Selection

Although exact costs depend on region, supplier, part size, and volume, some general distinctions can be made between hardcoat and Type II anodizing from a production perspective.

Processing Complexity

Hardcoat anodizing requires:

- Refrigerated tanks and higher energy consumption due to high current densities.

- More stringent control of bath chemistry and temperature.

- Longer process times and potential limitations on load size.

Type II anodizing typically runs at higher temperatures, with shorter cycle times and lower current densities, making it more economical and widely available for high-volume production.

Typical Cost Implications

In many cases, hardcoat anodizing is more expensive per unit area than Type II due to:

- Higher electrical energy usage.

- More demanding cooling and agitation requirements.

- Longer exposure time and increased maintenance of baths.

However, when hardcoat anodizing prevents early wear or corrosion failures, the overall life-cycle cost of the component can be favorable. Type II anodizing usually offers the best balance of cost and performance for parts that do not face severe wear or heavy mechanical loads.

Selection Guidelines: When to Use Which

Choosing between hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing requires matching coating properties to the application’s performance requirements.

| Requirement or Condition | More Suitable Option | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| High wear and abrasion resistance | Hardcoat anodizing | Higher hardness and thicker, denser oxide layer |

| Decorative appearance and bright colors | Type II anodizing | Better dye absorption and more transparent base film |

| Tight tolerance parts with limited dimensional allowance | Type II anodizing | Thinner films minimize dimensional change |

| Severe corrosion plus mechanical wear | Hardcoat anodizing | Thicker protective barrier and high wear resistance |

| Minimal cost for general corrosion protection | Type II anodizing | Lower processing complexity and shorter cycle times |

| Black, low-reflectivity functional surfaces | Hardcoat (often dyed black) | Natural dark tone and ability to achieve deep black |

| Colored consumer products with brand-specific hues | Type II anodizing | Wide color palette and consistent decorative finish |

Typical Pain Points and Constraints

In practical applications, engineers and manufacturers encounter specific constraints when implementing anodizing in designs.

Dimensional Tolerance Challenges

With hardcoat anodizing, the higher thickness and outward growth can lead to issues such as:

- Interference fits where components no longer assemble easily after coating.

- Changes in thread fit that increase assembly torque or cause galling.

- Variable thickness on edges versus recessed areas, affecting uniformity and function.

These challenges can be mitigated by designing appropriate pre-coating dimensions, specifying critical surfaces for masking, or using Type II anodizing where high thickness is not required.

Color Variation and Alloy Effects

Both hardcoat and Type II anodizing may show color variation between different alloys or even different lots of the same alloy. For visible, color-critical components, mixing alloys within one assembly can lead to noticeable shade differences. Type II decorative finishes are particularly sensitive to alloy composition and surface preparation. Consistent material selection, pre-anodize finishing, and process control are necessary to minimize visible variation.

Practical Specification Tips

Clear and complete specifications help ensure that the anodizing process delivers the intended performance.

Key Elements to Include in a Specification

- Type of anodizing: Hardcoat (Type III) or Type II sulfuric.

- Target thickness range, e.g., 40–50 µm for hardcoat or 10–15 µm for Type II.

- Color and dye requirements, if applicable (e.g., black dyed, clear, specific color code).

- Sealing requirements: sealed, unsealed, or specific sealing method.

- Critical dimensions and surfaces: indications for masking or post-process machining if necessary.

- Applicable standards or test criteria for hardness, thickness, and corrosion resistance.

Early communication between design, manufacturing, and the anodizing supplier is important to ensure that geometry, alloy, and specification are compatible with the desired anodizing type.

Conclusion

Hardcoat anodizing and Type II sulfuric anodizing are closely related processes that produce anodic aluminum oxide films with different performance characteristics. Hardcoat offers thicker, harder, and more wear-resistant coatings, making it suitable for demanding mechanical and industrial applications. Type II provides thinner, more easily dyed, and more economical coatings, ideal for decorative and general-purpose corrosion protection.

By understanding differences in thickness, hardness, wear behavior, color, dimensional impact, and processing requirements, engineers and designers can make informed choices that align with their application’s functional and aesthetic needs. Careful specification of anodizing type, thickness, color, sealing, and critical surfaces ensures repeatable performance and helps avoid common issues related to dimension changes, color variation, and service life.

FAQ: Hardcoat Anodizing vs Type II Anodizing

What is the main difference between hardcoat anodizing and Type II anodizing?

The main difference is coating thickness and resulting performance. Hardcoat anodizing (Type III) produces thick, dense oxide layers, typically 25–100 µm, with high hardness and wear resistance. Type II anodizing produces thinner layers, typically 5–25 µm, offering good corrosion resistance and excellent dyeing capability but lower wear resistance compared with hardcoat. Process conditions for hardcoat use lower temperatures and higher current densities, while Type II uses moderate temperatures and current densities.

When should I choose hardcoat anodizing instead of Type II anodizing?

Choose hardcoat anodizing when your aluminum component must withstand significant wear, abrasion, or harsh operating conditions, such as in sliding mechanical parts, hydraulic or pneumatic components, or heavily used industrial hardware. Hardcoat is also suitable when you need a dark, low-reflectivity functional surface. Type II anodizing is usually the better choice when the priority is appearance, colored finishes, moderate corrosion protection, or when dimensional change must be minimized.

Does hardcoat anodizing always provide better corrosion resistance than Type II?

Hardcoat anodizing often provides superior corrosion resistance because of its greater thickness and dense structure, especially when properly sealed and applied to suitable alloys. However, well-executed Type II anodizing with adequate thickness and sealing can also deliver very good corrosion performance in many environments. The actual resistance depends on coating thickness, sealing quality, alloy composition, and the specific service environment.

Will either anodizing process significantly change my part dimensions?

Yes, both processes change dimensions, but to different extents. Anodizing converts part of the aluminum surface into oxide and builds outward, typically with about half the coating thickness growing above the original surface. For Type II, this change is relatively small, often a few micrometers. For hardcoat, the change can be tens of micrometers and must be considered carefully in the design of tight fits, threads, and precision features. Coordinating thickness and tolerances with your anodizing supplier is important when specifying hardcoat.

Can hardcoat anodizing be dyed in colors other than black?

Hardcoat anodizing can be dyed, but its natural dark gray to black appearance and dense pore structure limit the range and brightness of colors. Black is the most common and reliable dyed color for hardcoat. Lighter or vivid colors are more difficult to achieve and may not appear as intended. If you require a wide choice of bright, consistent colors, Type II anodizing is generally the preferred option.

Is sealing necessary for hardcoat and Type II anodizing?

Sealing is highly recommended for Type II anodizing, especially for decorative and corrosion-resistant applications, as it closes pores and locks in dyes. For hardcoat anodizing, sealing is application dependent. Unsealed hardcoat offers maximum hardness and wear resistance but somewhat lower corrosion resistance. Sealed hardcoat improves corrosion performance and can be beneficial in corrosive environments but may slightly reduce surface hardness. The choice should be based on the required balance between wear and corrosion resistance.